After his marriage failed, my great-great-grandfather John Montgomery headed west from Manitoba, and picked up a large farm about five kilometres straight south of Fort Langley. He farmed there for a decade, until his death in 1900.

His son William, my great-grandfather, came west as well, a few years later, and retired to a home on West 23rd Avenue in Vancouver. He lived there with his second wife Hannah for almost a quarter of a century.

When William died in 1942 he was buried in the Mountain View Cemetery in Vancouver, within sight of his father’s grave. (Kind of funny, since by all reports, they did not get along.)

William’s daughter Maud married my grandfather William Elmer Obee. My grandparents lived for a while in Creston, but Maud died in Alberta in 1952. My grandfather died in 1965 in Invermere, in a home across the street from the one he helped my father build.

What does all of this have to do with the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives? Just about everything.

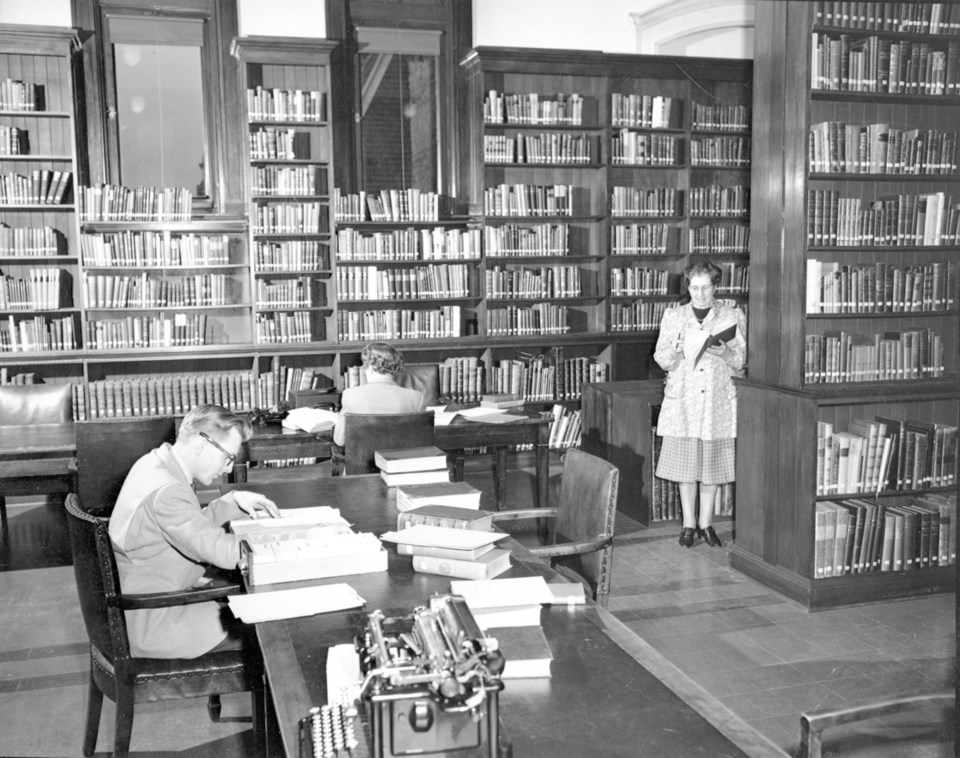

I have been researching my family history for more than 30 years, and the archives — housed right beside the museum itself, just under the carillon — has been a key source for much of my work.

Most genealogists start with registrations of births, marriages and deaths, and the archives has copies of the forms that have been made available by the Vital Statistics branch. On one glorious day in 1997, I was able to get the death registrations of three ancestors — my grandfather, my great-grandfather, and my great-great-grandfather.

That was possible because an index to the registrations had been placed online, thanks to the B.C. Archives. Complain about government agencies if you like, but our B.C. Archives was ahead of the curve in using the Internet as a way of making information more accessible to all.

Today, there is much more than an index. The registration forms have been placed on the Internet in two places — on the B.C. Archives website and on the FamilySearch website.

Genealogists would also want to check old newspapers, in order to find references to births, marriages, deaths and much more. Again, the B.C. Archives is the place to go, because hundreds of early titles are available on microfilm there.

Deaths create all types of records, including probate files. Thanks to the B.C. Archives, I was able to obtain copies of the wills of my ancestors who died here. (Wow, they had a lot of assets. None of it trickled down to me.)

To understand the lives of our ancestors, we need to know where they were. The holdings at the B.C. Archives include thousands of maps as well as land records. I could trace that land in Langley, as an example. My great-great-grandfather was not the original owner. For centuries before the arrival of settlers, it was home to indigenous populations.

After the land was grabbed by the newcomers, it was divided into sections and quarters, using the Coast Meridian as a reference point. A Crown grant to the first owner recognized by the provincial government bears the names of Robert Beaven and Joseph William Trutch.

Beaven was the chief commissioner of lands and works when his named appeared on that document. He was a member of the provincial legislature for 23 years, and served as premier in 1882-83. He was a mayor of Victoria in the 1890s. He was also one of the owners of the Victoria Daily Times soon after it was launched in 1884.

Trutch was the first lieutenant-governor, and his efforts to dismiss the indigenous peoples have been well recorded over the years. He set the tone for a lot of the anti-native sentiment that prevailed for years.

That document, for what it is worth, links my family to the history of Victoria, of this province, and this newspaper. Thanks to the B.C. Archives, I have a paper trail that gives me a stronger connection to the province of my birth.

The land settlement records at the B.C. Archives include federal homestead files for the Railway Belt, along the Canadian Pacific mainline, as well as provincial pre-emption records, which also give information about homesteads as well as the people who took them up, including returned soldiers.

And don’t ignore documents dealing with law and order, such as early police and prison files and Attorney General records. They take a bit of digging, and you might not find your family members in them, but they are fascinating.

Also available are divorce and bankruptcy records, as well as the coroner’s inquest and inquiry files. Searching in those a few years ago, I came across the fascinating Charles Marble, an aeronaut who drowned in the Fraser River near New Westminster in 1894 when the hot-air balloon he was riding in fell from the sky.

There is more. The collection of directories on microfilm helped me to trace my great-grandfather’s time in Vancouver, and develop a sense of what his neighbourhood was like when he was living there. The photograph collection helped me see my ancestral villages, towns and cities throughout British Columbia.

The collection of photographs includes images taken by a wide variety of people all over the province, and includes some photos that originally appeared in the Victoria Daily Times and the Daily Colonist.

Occasionally, some parts of the collection stretch beyond the borders of British Columbia. These non-government, non-British Columbia sources have helped me as well.

More than a century ago, the Canadian Pacific Railway hired a journalist named Alexander Begg to compile a survey of settlers in Manitoba. He sent questionnaires to a few hundred people, including four who are related to me.

Begg’s research was used in a series of promotional booklets produced by the CPR to entice more settlers to move to the Prairies, where nice weather and certain success awaited them. He kept the original copies of the questionnaires, and brought them with him when he moved to Victoria.

Those forms ended up in the holdings of the B.C. Archives, making it possible for me to read the comments of my homesteading relatives in their own handwriting. Great stuff.

These sources are just the highlights, some of the most-used collections for family historians. There is much, much more, waiting for you in that building on Belleville Street, in the records and documented history of our province.

Dave Obee is the editor-in-chief of the Times Colonist, and the author of several books on genealogy and British Columbia history.