This is the first of a series of columns by specialists at the Royal B.C. Museum that explore the human and natural worlds of the province.

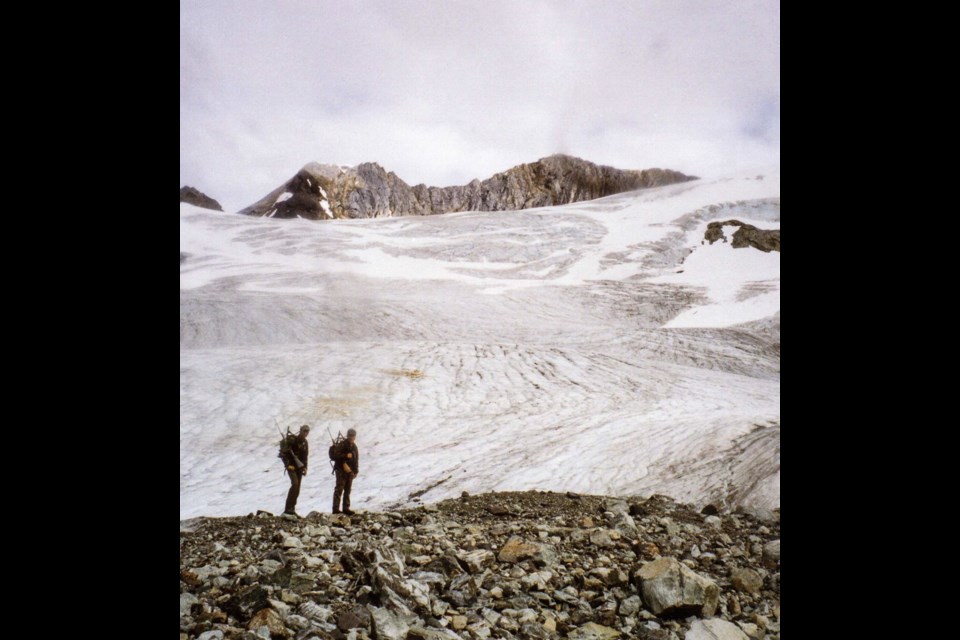

In 1999, during one of the warmest years on record, three sheep hunters encountered human remains on a small icefield on the north side of an unnamed mountain in Tatshenshini-Alsek Park, in the northwestern corner of B.C.

Fortunately, the hunters were aware of the potential significance of the discovery and recognized their responsibilities. They quickly contacted the appropriate people, and the work set out in a respectful manner and with full collaboration between the nearby Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, scientists and government institutions in a way that made the project unique. Champagne and Aishihik First Nations named the find Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi — Long Ago Person Found.

Examinations at the Royal B.C. Museum revealed that the remains were those of a young man about 18 years old at the time of death. He was healthy, of average body build and about 170 cm (5’7”-5’8”) tall. There were no markings on his skin or evidence of animal scavenging.

There was a break across the top of one lower leg bone, but it had occurred at or after the time of death. The teeth showed notable wear in some cases with crown height reduced by one-half. Internal organs were flattened back to front, as might be expected in such a find and the stomach contained a mass of material from a recent meal.

Researchers also studied a fur robe and pouch preserved in excellent condition along with the remains; belongings made of such materials are rare finds. These studies provided remarkable insight into the design and manufacture of such items. They also preserved traces of the activities of the Long Ago Person Found.

The large (204 by 110 cm) blanket-shaped robe consisted of 95 arctic ground-squirrel pelts, stitched together side by side in a pattern still used by the Dän and evident in robes in museum collections. The pelts were joined with fine sinew, the stitches about three mm apart.

The sinew used for sewing the pelts together came mostly from moose (Alces alces), and surprisingly, one patch had been repaired with sinew from a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Two other species, humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), were identified in another piece of two-strand sinew. The recognition of sinew from two species of whales highlights the coastal connection to the inland discovery site.

Although this story is about a person and a people, the natural landscape played a profound role in its unfolding. The Tatshenshini-Alsek landscape is breathtaking in its variation, from verdant oceanside forests to bleak, craggy mountains and massive glaciers. Visitors from outside might view it as a harsh land with strong coastal-to-inland contrasts, but it is rich in plant and animal resources that were well known to the Indigenous people of the region.

Glaciers are among the most formidable and dynamic elements of the Tatshenshini-Alsek landscape, and glacial ice played a central role in the Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi discovery and its evolving story. Special circumstances in the character and behaviour of the entombing glacier led to the exceptional preservation of the human remains and belongings, and extraordinary circumstances also led to the melt that exposed those materials.

Material frozen in ice has the potential to be preserved almost unchanged for millennia, as was demonstrated by the discovery of the frozen human remains of a man now known as Ötzi in the Italian Alps. Unlike a block of ice kept in an ultra-cold freezer, glaciers are living ice; their structure can change, and they require special conditions to form.

The unique requirements of glaciers help explain how the human remains and belongings of the Long Ago Person Found came to be preserved, why they were discovered, and how they remained largely intact until they were found.

The site’s isolated location and fickle weather imposed tight constraints on work with and recovery of the remains. These conditions permitted only a few short visits to the site, yet a remarkable amount was accomplished. Field activities were respectful of the human remains and held to an extremely high standard.

The result was the recovery of study material that could undergo the most rigorous analysis. Just as significantly, respect for the person who lost his life, and for the traditions and cultural practices of the region’s Indigenous peoples, were foremost in the minds of all involved in fieldwork activities.

Many of the belongings and much of the biological material that was recovered came from plants. Until the time of the discovery, the study area’s flora was poorly known, especially elements of the moss and algal life. Botanical collections from the study site and adjacent area added much to our understanding of the region’s natural environment.

Most importantly, improved knowledge documentation of the flora provided key insights to help unravel the travels and activities of the Long Ago Person Found before he perished.

The age of ancient human remains and belongings is central in decoding the human story. Obtaining a reliable age for the discovery site posed several challenges. Eventually, radiocarbon dates on various items and the body itself demonstrated that the site represented several centuries of material.

Repeated strategic dating revealed that the Long Ago Person Found had perished about 200 years ago, during the time when Europeans were first making contact with this part of North America but had yet to visit the discovery region.

The Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi discovery is about more than science and history. This individual from long ago times has helped make new connections and build bridges not only between people and organizations, but between the spiritual, secular and scientific worlds. We hope you, too, will be inspired to embrace the many teachings from the Long Ago Person Found, who lost his life crossing a glacier so many years ago.

The book Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi: Teachings from Long Ago Person Found is available at local bookshops, the Royal B.C. Museum Shop and online through the Royal B.C. Museum at publications.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

Richard J. Hebda, curator emeritus of botany and earth history, joined the Royal B.C. Museum in 1980 and retired after 37 years in 2017. He was curator of botany and earth history from 1986 until his retirement and remains active in museum research projects. He studies plant fossils and their distribution in time and place to uncover the history and evolution of B.C.’s landscape, ecosystems and climate.