When history professor Barry Gough retired to his native Victoria, he ended up surrounded by watery echoes of the Royal Navy’s first attempt at globalization.

Names like “Denman” Island and “Moresby” Island are both in honour of Royal Navy officers and are just a few of the reminders for Gough that British Columbia’s first contacts with Great Britain were through the Royal Navy.

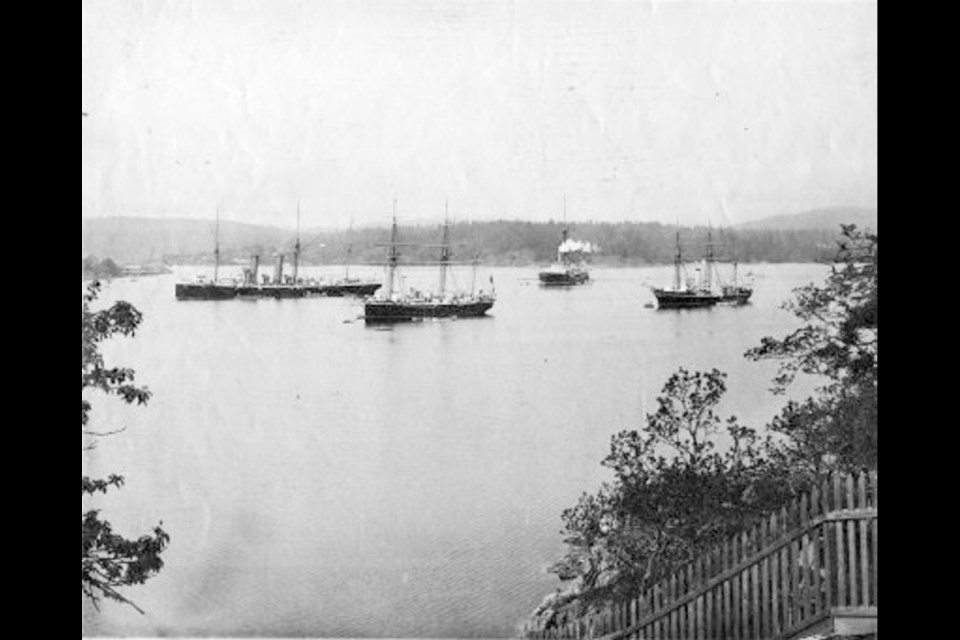

But for the 77-year-old Gough, those names are also reminders that Victoria, notably the Port of Esquimalt, was a naval outpost holding down the northern Pacific corner of Britain’s global empire, which covered almost every ocean in the world.

“All these naval bases became the anchors of empire,” said Gough in an interview in his Saanich home. “Esquimalt is one of the anchors of empire, but so, too, is Capetown in South Africa and Trincomalee in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, and others.”

So it’s no surprise a return to Vancouver Island, where Gough was born, also provided inspiration and source material for his latest book, Pax Britannica, Ruling the Waves and Keeping Peace before Armageddon. The British Maritime Foundation recently awarded the book the Mountbatten Maritime Award 2015, for best literary contribution to the understanding of the importance of the seas.

It’s also the first non-fiction account specifically devoted to the Royal Navy’s part in establishing the British Empire. For Gough, it was an oceanic empire covering the entire world, and it was the Royal Navy that secured the waterways and made them safe for commerce and trade.

Gough can trace his interest in the history of the Royal Navy back to 1965 and his student days when he was headed off to King’s College in London for post-graduate research. He wanted to complete a thesis about B.C. and was told the story of how Esquimalt became a naval base had never been written.

Despite the misgivings of his professor in London, Gough completed the research and it became his first book, The Royal Navy in the Northwest Coast, published in 1971.

Gough later taught history at Western Washington University in Bellingham and became a full professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont., from 1972 to his retirement in 2004. Today, he still writes and regards himself as a historian of empire and naval issues.

He also likes to give some career credit to a life experience that has mostly kept him distant from the workings of any navy, including the Royal Canadian Navy. Even Gough’s military experience was limited to the Canadian Air Reserves.

“It’s been said to me 100 times: ‘Oh, you must have been in the navy,’ but no,” Gough said.

“To some degree, I’ve always regarded that as a benefit,” he said. “It’s not that naval officers can’t be good historians, but I think a detached viewpoint is a benefit for an independent mind.”

His latest book is in some ways a return to the theme he first explored in his look at Esquimalt. But in Pax Britannica, he examined the global reach of the Royal Navy and its role in the formation of the British Empire, from about 1815 with the final defeat of Napoleon until 1914 and the start of the First World War.

For Gough, the Royal Navy has always been a remarkable institution. Also, he said, during that period it truly did “rule the waves,” even if, at times, relatively junior officers commanding gunboats might “waive the rules.”

The Royal Navy acted under a Royal Charter and so was a direct instrument of government. Naval officers joined young, served long apprenticeships as juniors and moved up after passing examinations at review boards.

In contrast, the British Army answered to the War Office and expected its officers to be wealthy enough to purchase their own commissions and promotions.

With the British government during the 19th century very interested in expanding trade, the Royal Navy became its instrument in making that happen. The Industrial Revolution had turned Britain into a manufacturing powerhouse. It was the Royal Navy that allowed British goods to arrive safely in good delivery time.

“The profit that is made from the Industrial Revolution becomes the driving engine for naval power,” Gough said. “The navy becomes the guardian of commerce.”

“So I’m always looking at profit and power and how they are interrelated,” he said.

But for Gough, it’s also a heroic, even noble and romantic, story.

One of the Royal Navy’s first tasks was the suppression of piracy, then endemic around the world. Ships were dispatched to the West Indies and South American coasts, where the shrinking of Spanish control had left a hole filled by criminals. Anti-piracy also continued into the South China Sea, where Hong Kong was another naval outpost of empire.

The Royal Navy was also one of the first effective instruments used to fight the slave trade. In 1807, the British Parliament voted to abolish slavery, and made it illegal in the entire British Empire in 1833. The British government expected and directed the Royal Navy to execute its wishes.

“It’s a wonderful story,” Gough said. “Piracy and slavery always get people excited.”

“The British are nominally great pacifists and always talk a great pacifist line,” he said. “But when they make up their minds, they can actually become quite militant and will follow things through.”

The slave trade didn’t really end until the U.S. Civil War, 1861-1865. But Gough argues it was the Royal Navy that first exercised a legal and moral restraint. And reminders for him, even now, are everywhere.

Denman Island, for example, was named for Joseph Denman, a rear admiral in charge of Esquimalt. But Denman first drew notice as a lieutenant and later a ship’s captain who battled slave traders in Africa.

Likewise, Fairfax Moresby, who gave his name to Moresby Island, fought pirates in the Mediterranean and took action against slavers before finishing his career as a rear admiral, also in charge of the station at Esquimalt.

Gough’s exploration of the century of Pax Britannica also explores its end times. In the latter half of the 19th century, the Royal Navy started to feel itself squeezed by other naval powers: the U.S., Japan, Russia and most notably, Germany.

It was forced to make adjustments. For Gough, an important early step was the courting of a co-operative effort with the Americans, always fine sailors and shipbuilders themselves. Gough devotes an entire chapter to this beginning.

He also notes the catastrophic end in 1914, when the First World War started.

Prior to that, the British government might have recognized, even forestalled, the passing of the Royal Navy’s prominence with a great building program. It started in 1906 with the launching of HMS Dreadnought, the world’s first all-steel, all big-gun, steam-turbine-driven battleship.

But the First World War, and its four years of massive casualties, shattered the treasuries and the governments of much of Europe. For Gough, it also sapped the political will of Britain to maintain the Royal Navy.

“Navies are very capital intensive,” Gough said. “Ships have to be built and designed over a long period of time.

“Political will and the ability to finance navies are the two most important things,” he said.

And while it is outside the scope of his latest book, Gough said it is now the Americans who rule the waves and have taken over where the Royal Navy was forced to sail back.

“The Americans are the only ones who have made that commitment,” he said. “They invest in their navy and they keep re-investing in their navy even though it’s becoming increasingly expensive for them.

“And their political will is very strong,” said Gough.

Pax Britannica is published by Palgrave Macmillan.

[email protected]