Michael Morris is one of Canada’s foremost living artists, winner of both the Governor General’s Award and the Audain Prize.

Michael Morris is one of Canada’s foremost living artists, winner of both the Governor General’s Award and the Audain Prize.

Born in 1942, he was a precociously talented child of an artistic mother, Rita Morris, and grew up in Saanich, where he still lives. Morris has blazed a path through the art world with a brilliant career as a painter, performer, archivist and thinker, and is active in Canadian, American and European centres. Currently, the work he created in Berlin in the 1980s is on show at Winchester Galleries at 665 Fort St.

In the course of an interview with the artist at his Brentwood Bay studio last week, I learned a lot about his connection with Berlin. It’s not what I expected, as Morris and his mother Rita had emigrated from Britain in 1946, after her husband, Michael’s father, a Canadian, was killed in action in Sicily in 1943.

As a child, young Michael was powerfully influenced by Herbert Siebner, who arrived here from Berlin in 1953 and lit the fire of modernism in Victoria. Morris was also mentored by Maxwell Bates, who arrived in Victoria in 1962. Bates had been a prisoner of the Germans throughout the Second World War and later studied with the German Expressionist artist Max Beckman in New York.

The influence of other German and Austrian artists was powerful in Victoria. Jan and Helga Grove and Richard Ciccimarra were active on the scene, as was the enormously stimulating filmmaker Karl Spreitz.

Morris left Victoria to study in Vancouver in 1962 and then at the Slade School in London in the 1965.

“My grandfather had a publishing business, with offices in London and Berlin,” Morris said. “My mother spent her summers with her cousins in Berlin, so I had that sort of thing, never all that Nazi-hating German stuff, to grow up with.” Thus, he was open to the European part of Victoria’s art history when he discovered it.

Morris recalled that at art school in Vancouver, Jack Shadbolt sat him down and said: “You’ve got some talent, but you’ve had this influence of all these Europeans” — Siebner and Ciccimarra.

“They all have to learn how to be Canadian,” he explained. Shadbolt’s advice? “Forget everything they ever taught you.”

Morris ignored this advice. In the early 1980s, his considerable success in Canada threatened to entrap him as an administrator. In 1981, he accepted a residency in the German Foreign Artists Program and moved to Berlin, where he was once again a free spirit.

That was also the year that the first AIDS outbreaks came to San Francisco, and by 1984 it was an epidemic.

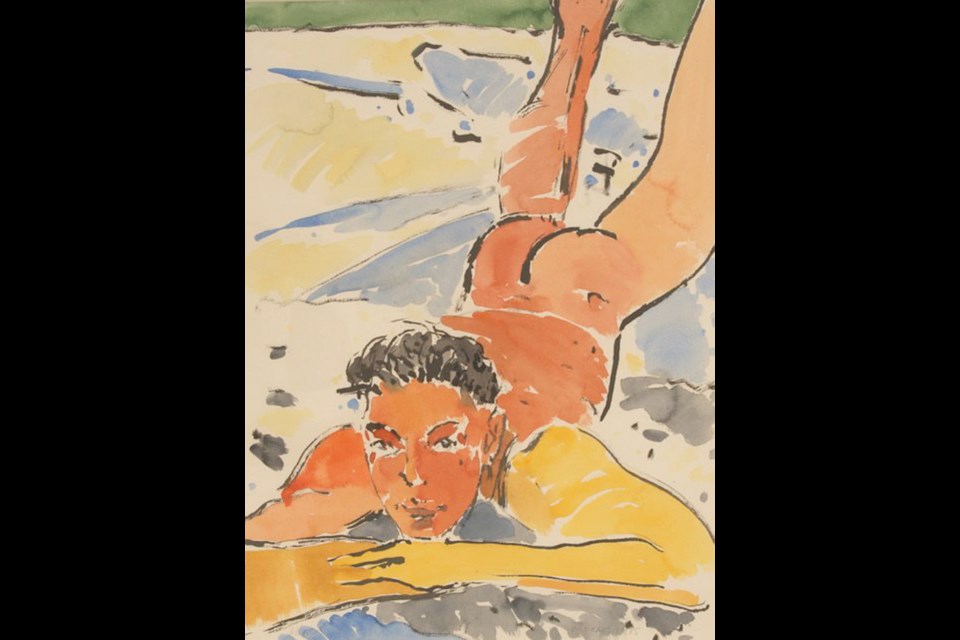

“It hit Berlin like a tsunami, the art scene particularly,” Morris reflected. “It was a dark time.” It was then that he created the ink and watercolour studies of boys lolling about in his studio, which are featured in the current exhibition. The boys appear to be on the seashore, but Morris let me in on the context — they are survivors looking out over the rubble after the AIDS tsunami has laid waste their environment.

I have always admired the technique of these watercolours, reminiscent of David Hockney or Egon Schiele. People would come by Morris’s studio, to make tea and change the records, while Morris drew and drew. How did he do it? The black lines were drawn first, with an old worn-down brush. Morris also cut the end off the brush’s wooden handle to make a blunt nib. Later, he’d colour these ink drawings with pooling watercolours.

During the 1980s, Herbert Siebner and his wife Hannelore sometimes came to visit him in Berlin, and Morris more than ever appreciated what the senior artist was about.

“Siebner had a huge talent,” Morris said, “and if he had continued in Berlin he’d be a major figure today.”

At Winchester Galleries, across from the paintings of the boys, are some larger — and more serious — abstract canvases.

“I was reading Dante’s Inferno at the time,” he explained, and then he quoted Dante: “In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself in the middle of dark wood wherein the straight way was lost.” It seemed that the Cold War would never end, and the conservatism of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher was just coming to the fore. “It was like that,” he mused.

Some of the abstract paintings are inscribed with the line markings of a tennis court. Morris told me: “All the old embassies were along the Tiergarten, ruins from before World War II. They were beautiful edifices in various stages of falling apart, with abandoned tennis courts, leading directly to the Brandenburg Gate and the Wall.”

I asked about a series of cones falling down the right side of the painting. Brancusi? Noguchi?

“No,” he explained. “When they rebuilt in Berlin, they had these kind of cones where the ruined parts were poured down to the street below.”

So the sunlit beaches are truly fields of rubble, and the mysterious abstract paintings are bristling with symbolic forms. An understanding of the context of this art has added to my understanding and appreciation. But with or without the stories, these are objects of considerable beauty.

Michael Morris: The Cold War, A Winter’s Tale, until Oct. 28, Winchester Galleries, 665 Fort St., winchestergalleriesltd.com, 250-386-2777.