Melvin Gurr, the last surviving member of the defiant crew that built the so-called Freedom Road from Bella Coola to Anahim Lake 63 years ago, snorts at the suggestion the steepest and most treacherous part should finally be paved.

“I don’t see how that would make any difference,” said the 84-year-old Gurr. “It’s fine just like it is.”

His wife Elaine, however, now does the driving and she has other thoughts.

“I’ve been in Bella Coola for over 50 years and I still don’t like driving The Hill,” she said.

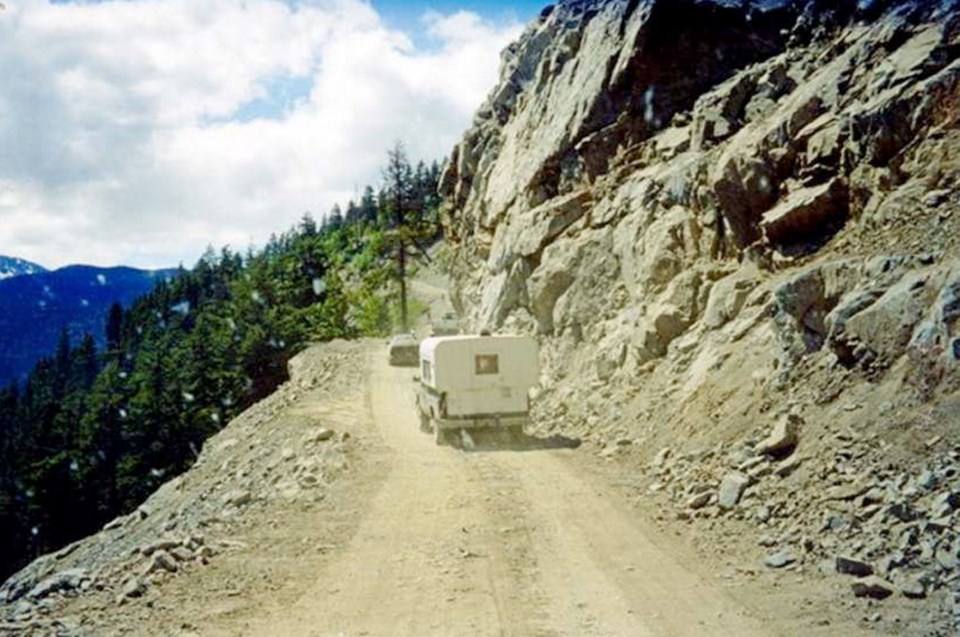

The Gurrs are talking about a legendarily steep, narrow and twisting section of Highway 20 that drops 6,000 feet from the high Chilcotin Plateau through three switchbacks down through the Coast Mountains to Bella Coola. It is such a white-knuckle gravel road that on occasion tourists who have ventured down it have refused to return on it.

Their alternatives: fly out or take the infrequent ferry service.

Melvin Gurr had a lot to do with that section of the road. It was his dynamite, carefully packed into the hard rock faces along the Atnarko River route, that created a small trail for an ancient TD18 International bulldozer to beat into a narrow road. He was part of a group of residents from Bella Coola that decided to build the road after the province stopped construction of Highway 20 from Williams Lake at Anahim Lake, just before the mountains. Going the final 76 kilometres to the ocean was deemed too difficult and expensive.

But locals disagreed, and relying on the same intestinal fortitude that allowed them to settle the wild Chilcotin, they punched a road through in just over a year at a cost of $62,000, all but $4,000 of it eventually covered by the province. At today’s value, that’s just over $570,000. By comparison, simply paving a single kilometre of gravel road is now estimated at $400,000.

Today, the road is wider in many places and the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure has built up a decent road base. The province has paved all but 42 kilometres of the highway between Williams Lake and the coast. But much of those unpaved kilometres belong to The Hill and a section leading to Anahim Lake.

The road is not for the faint of heart. Unpaved through the most narrow and winding portions, the dizzyingly steep section through Tweedsmuir Provincial Park has defied attempts to tame it. It is still a single-lane road in some places, and there are no guard rails on the precipice edges.

The three local tourism associations in the central coast, Chilcotin and Cariboo, as well as the Aboriginal Tourism Association of B.C., have lobbied to have much of the unpaved section of the highway upgraded. Between the difficult conditions of the road and the recent downgrading of ferry service between Bella Coola and Port Hardy, the region has not enjoyed the same growth in tourism as other parts of B.C.

Last month, a group of First Nations, tourism associations and tourism operators called the Mid-Coast B.C. Ferry Working Group presented a report to government showing that while aboriginal tourism was up more than 100 per cent across the province, transportation challenges in the mid-coast and Chilcotin had limited the growth to only 15-20 per cent.

“I think it is in Canada’s best interest, as well as British Columbia, to improve that access into Bella Coola,” said Pat Corbett, the president of Cariboo Coast Chilcotin Tourism Association and the co-chair of the working group.

“There is no reason why they couldn’t pave the road to the top of The Hill and we wish that would be done,” he said. “I think it is a forgotten part of the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure.”

Every year, the highway attracts tourists who use it to access the Great Bear Rainforest, the large swath of now-protected central coast. Many are from Germany, Holland and the Scandinavian countries. But it also attracts Americans. Last month a North Carolina lawyer, Donald Pevsner, wrote to Transportation and Infrastructure Minister Todd Stone demanding to know why The Hill was not yet paved. Pevsner plans to drive Highway 20 this summer and was miffed that some sections are still dirt.

“I am appalled that the most difficult 35 miles of this 284-mile-long road is unpaved dirt, through Tweedsmuir Provincial Park,” he wrote. “I find it totally incomprehensible and unconscionable that your Ministry has not paved this stretch of Route 20 decades ago.”

In an interview, Pevsner said he’s driven in B.C. before and doesn’t understand the logic of leaving a major highway unpaved.

“I like driving exotic roads, but I don’t get why they haven’t paved the roughest part through the park,” Pevsner said.

Norm Parkes, the executive director of highways for the province, says there’s a good reason for The Hill to remain gravel.

“It is very much subject to weather conditions. It goes from the dry Chilcotin Plateau down to sea level. It is a very coastal climate. If we were to pave it, it would become a skating rink in winter,” he said. “We keep it gravel for safety reasons.”

The entire highway has undergone more than $50 million in upgrades during the last eight to 10 years, he said, and this year another $6.2 million will go into repaving some sections outside of Anahim Lake and Bella Coola.

Parkes said there are no plans to pave The Hill but some sections at the top may be paved in the future, time and budget permitting.

For all its legendary treacherousness, The Hill doesn’t have a high crash history, according to both locals and the ministry. Over the years a few people have been killed or injured, but less than the average of other highways. Parkes has a theory about why.

“I think people respect the road. When I drive it I certainly do. It is a challenging road and you need to respect it,” he said.