First Nations are raising concerns about plans by the B.C. Liberal candidate for Saanich North and the Islands to build a swimming pool on an archeological site near his waterfront home on Salt Spring Island.

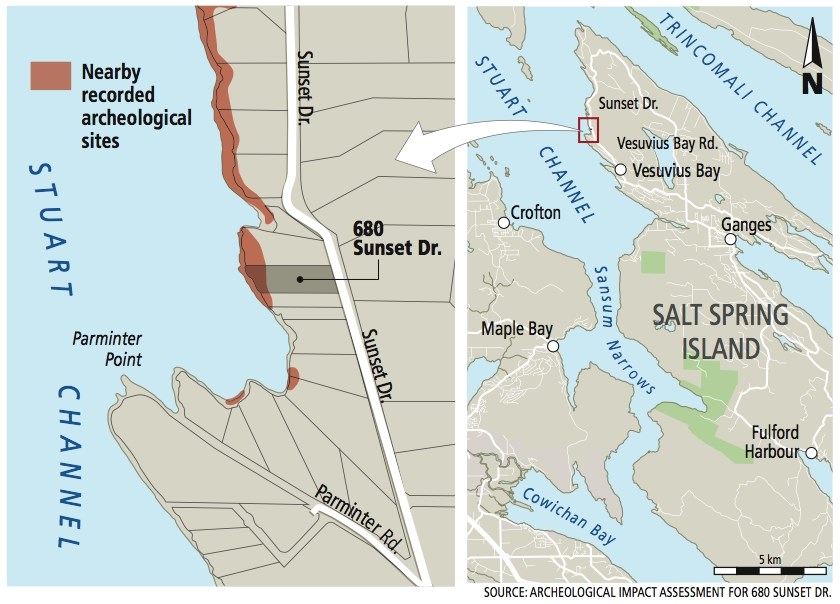

Stephen P. Roberts has applied for a site alteration permit at 680 Sunset Dr., where he intends to build a cabana, hot tub and two-lane, infinity-edge lap pool overlooking the ocean.

His first application was approved and then suspended in 2016 after First Nations complained that the development endangered what they say is a nearly 2,000-year-old village and burial ground that extends for about a kilometre along the waterfront.

Roberts, who said there is no evidence of a burial ground on the property, submitted a revised application in January. The archeology branch in the Ministry of Forestry, Lands and Natural Resource Operations sent First Nations a letter on March 31 seeking their comments, documents show.

Cowichan Tribes responded to the government by email this week, expressing frustration with Roberts for persisting with the project and the government for continuing to entertain it.

“Despite our expressed concerns, it is clear that Mr. Roberts’ plans remain unchanged in his efforts to build his 100 ft swimming pool, hot tub and cabana directly atop of this large, deep ancient First Nation settlement and burial ground,” states the email, a copy of which was provided to the Times Colonist.

“Like at Grace Islet, we believe that such development and land use is inappropriate and demonstrates a fundamental disrespect of, if not contempt for, our ancestors, our ancient heritage and First Nations peoples in British Columbia.”

Chief William Seymour said in an interview that the pool project raises questions about the B.C. Liberal Party’s commitment to reconciliation with First Nations.

“You can’t be campaigning and promising that you’re going to acknowledge truth and reconciliation, you’re going to acknowledge the presence of First Nations and turn around and decide to put a swimming pool over one of our archeological sites,” he said. “That doesn’t make sense.

“Either you’re going to do it or you’re not. Don’t say you’re going to recognize it and turn around and you don’t care about our archeological remains. That’s two-faced to me and that’s the way every First Nation person will look at somebody that promises one thing and does another.”

The Lyackson First Nation sent an equally blunt letter opposing the application. “While the amended application does not include bulldozing, the development still intends to physically disturb deep and significant archeological deposits, including likely burial features and ancient human remains,” writes Linda Aidnell, land and resource co-ordinator.

Roberts initially said Tuesday that he was unaware that the application process was proceeding or that First Nations had been asked to comment. “You can extend a permit application just to keep it open, so it doesn’t have to be redone again,” he said.

“Maybe the archeologist has done that, but I haven’t talked to my archeologist in a while. I’ve been kind of busy.”

He said the project had been on hold since it was suspended in 2016 when the government requested a more detailed mitigation plan.

“I’m not pushing ahead with it,” he said. “Like I just said, it’s been in abeyance.”

He later called back to say that when the application was renewed at the end of December, his archeologist was required to submit a new engineering proposal for building the pool without impacting the site.

Roberts said that, unbeknownst to him, the proposal was completed and submitted to the archeology branch, which reviewed and accepted it and forwarded it to First Nations for comment.

“I thought they were just going to apply for an extension and we would come back to it at some later date,” he said. “I just wanted to reiterate that I’ve been following the process scrupulously, as have the contractor and the archeologist.”

Roberts said he has not seen the letters from First Nations, but stressed that he is abiding by the requirements of the archeology branch.

“The branch doesn’t say you’re not allowed to build on these sites anywhere in the province,” he said. “They say you have to follow our rules on how you would build and you have to mitigate the way we tell you.”

Roberts said he first became aware of the archeological site when he applied for a building permit in 2015 and was told that he needed to get an archeological impact assessment. That assessment concluded that while there had been moderate disturbance to the site in the past, the remaining cultural deposits were relatively intact, documents show.

The archeologist made a number of recommendations, but said “the most viable option for the proposed development is the relocation of the development further east and outside of the archeological site boundaries.”

Roberts said he opted to submit a mitigation strategy instead. Asked why he didn’t move the pool, he said: “[The archeologist] actually gave three options and we wanted the site to be a little bit closer to the water.”

He noted that there was nothing in the assessment indicating that the property was a burial ground. “If the archeologist said that, it would probably have led to a very different mitigation requirement from the branch if it did,” he said. “I just do as the branch says.”

Roberts insisted that he’s sensitive to First Nations’ concerns, has met with First Nations on the property and has plans to include First Nations elements into the project’s architecture.

“I’m a collector of First Nations art,” he said. “I appreciate First Nations culture. I’m just doing what I’m asked to do every step of the way. The branch, if they said it’s a no go, they would have said that by now.”