The Lyackson First Nation’s creation story says that its people descended from the sky, down a very tall Douglas fir tree.

They wished to live on the tree, and asked a mystical creature to fell it. But the tree snapped in the process and became what are now Valdes and Galiano islands. That’s how the Lyackson (which literally means “top of Douglas fir”) came to inhabit Valdes Island in the Strait of Georgia.

“These stories have been passed down through generations, and we want to keep them alive for our elders to share with the community,” said Kathleen Johnnie, Lyackson land and resources co-ordinator.

Documenting and sharing stories, from thousands-of-years-old myths to contemporary land use, is particularly crucial to Lyackson. The First Nation no longer has an inhabitable reserve, and its 300 members have dispersed along Vancouver Island and as far as away as New York and Britain.

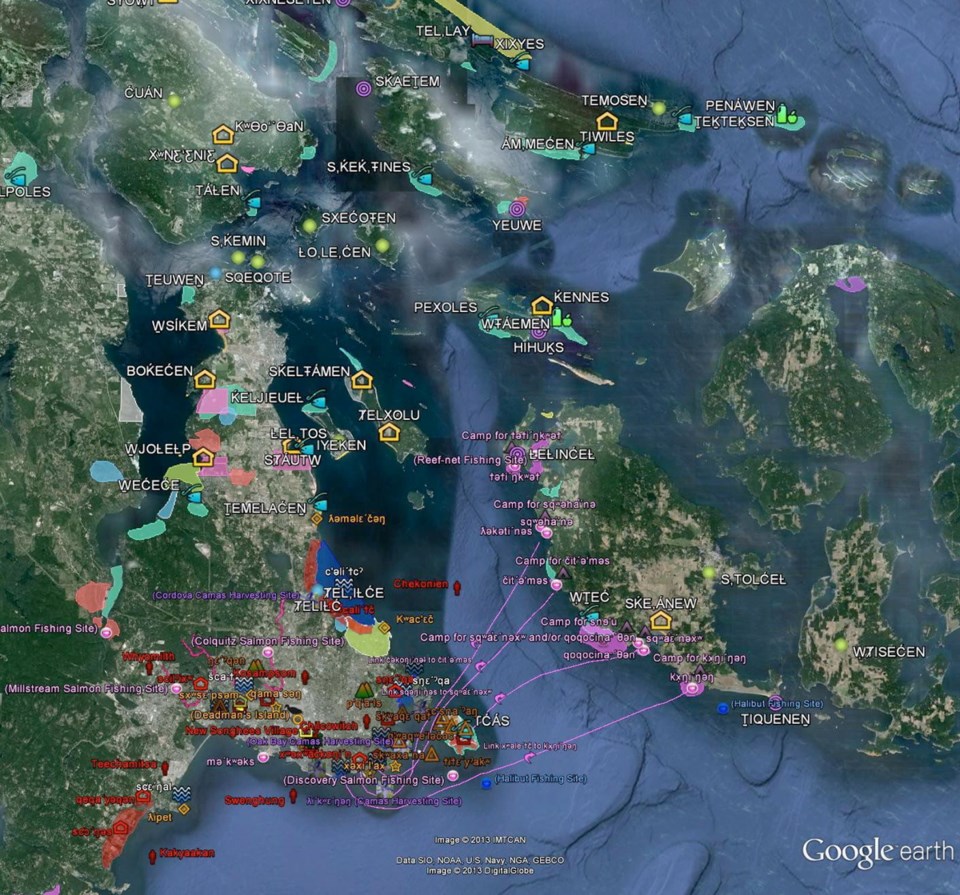

“We need to be able to connect and have our community involved,” Johnnie said. She is helping co-ordinate mapping of Lyackson members’ migration using Google Earth and Maps, as well as traditional place names and practices of Hul’q’umi’num’ Treaty Group nations, mainly in parklands.

Lyackson will be among about 100 participants in a four-day indigenous mapping workshop at the University of Victoria from Aug. 25 to 28. The workshop will explore how geospatial technologies can be used in indigenous mapping projects, with about 40 First Nations sharing how they are mapping traditional territories and land use.

Steven DeRoy, director of the Victoria research co-operative the Firelight Group, will speak about direct-to-digital methods that are replacing paper mapping.

Staff from Google Earth Outreach will show how to best use the widely accessible Google Earth to explore and map territories.

“Indigenous communities in Canada have been at the forefront of applying Google Earth and Maps as innovative tools in preserving traditional culture and managing lands and livelihoods,” Raleigh Seamster, program manager for Google Earth Outreach, said in a statement.

“We hope to put our mapping technologies in the hands of even more indigenous people through this workshop.”

UVic anthropologist Brian Thom, who is co-organizing the workshop, is at the forefront of indigenous mapping research in Canada — using online tools such as Google Earth and Maps that he says have democratized the process by being free and simple to use.

“Google Earth is easy, it’s free and you don’t need a GIS [geographic information system] to use it,” said Thom, who started his mapping research 20 years ago using a pen, paper and government topographical maps while walking through the wilderness.

“Now you can take a laptop to an elder’s living room and we’ll fly through Google Earth to places they recognize and know in their territory. … It puts the technology in the hands of indigenous people to use.”

Thom said a conversation sets the terms of how the mapping information is collected and shared, and with whom. For example, sacred sites and food source locations might be protected. He said bridging an oral tradition of knowledge-sharing with new technology has the added benefit of connecting elders with youth.

“In the Stz’uminus places project [which maps original Hul’q’umi’num’ names and cultural uses], the youth were excited to be recording elders’ stories with their cellphones and the elders were excited to be asked questions by the young people,” said Thom, who has worked as a researcher and treaty negotiator for First Nations and is the founder of UVic’s Ethnographic Mapping Lab.

The Lyackson, Hul’q’umi’num’ and Stz’uminus (Chemainus) mapping projects are all part of his ongoing research, which received a $75,000 Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant and additional funding from Google. He is also working with an indigenous community in Russia.

Thom said a focus of the workshop will be the legal implications of indigenous mapping of traditional areas for title and treaty negotiation purposes in B.C.

“The indigenous mapping movement is empowering because it is accessible, accurate and defensible,” said Thom, noting the information gathered could be used in everything from pipeline and fisheries discussions to land use and land rights.

“The Tsilhqot’in ruling is on everyone’s mind,” said Thom, referring to the recent Supreme Court judgment that gave aboriginals decision-making power where land claims are in effect. “It answered a major question about whether land rights are territorial in nature, giving us a new energy in our research.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs (co-sponsors of the mapping workshop) said the Tsilhqot’in decision will provide a focal point and real-life example for the workshop.

He said the technology and access will clearly lay out boundaries of aboriginal territories, which is “fundamentally important to be able to demonstrate the intensive use and occupancy of our traditional territories over many hundreds of years.”