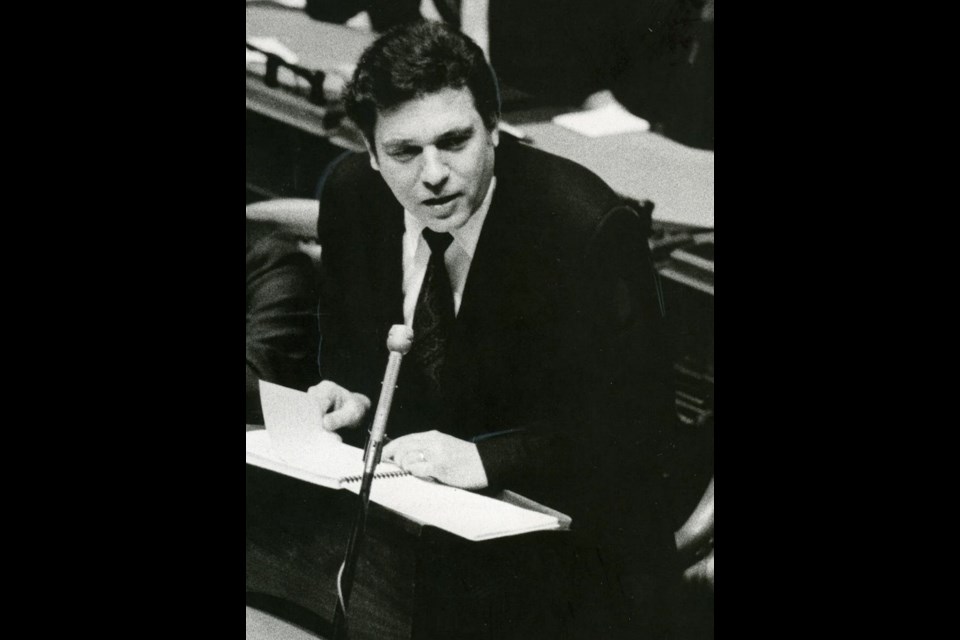

Dave Barrett, a wisecracking and flamboyant left-wing politician from east Vancouver who became British Columbia’s first NDP premier, died Friday morning in Victoria after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s.

He was 87.

Barrett had a significant impact on B.C. during his short three-year term in office, creating the Insurance Corp. of B.C. and the Agricultural Land Reserve, which were kept in place by the Social Credit and B.C. Liberal governments that followed.

The 26th premier of British Columbia led the province between 1972 and 1975.

It was a time of tumultuous change, with the NDP passing a new law on average every three days while in power.

His government’s reforms ranged from initiating a labour relations board and launching pharmacare to banning spanking in schools and pay toilets.

He lowered the drinking age to 19, increased the minimum wage, preserved Cypress Bowl for recreation and established the air ambulance service.

Barrett, who laced his social democratic politics with more than a dollop of humour, called himself “fat li’l Dave” after reporters in the legislative press gallery called him the “little fat guy.”

Barrett once told a reporter, with faux indignation: “[My opponents] have called me everything over the years. They’ve even called me fat.

“They’ve called me a Marxist. I say which one — Groucho, Chico or Harpo? I’ve always got reaction. I can deal with whatever anyone throws my way.”

Barrett’s shoot-from-the-hip style on the stump endeared him to the NDP faithful while angering his Socred opponents, who regarded him as the leader of the “socialist hordes.”

In his later career, as a candidate for the federal NDP leadership, Barrett summed up his style this way: “In my political career I’ve always been blunt, very blunt. As a consequence, either people love me or they hate me. There’s not much middle ground. That’s really how I operate.”

Shortly after he was elected premier, during a visit to Ottawa, he said to then-prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau: “I didn’t come here to B.S.”

In 1983, during a round-the-clock debate over the governing Socred’s spending restraint program, Barrett was physically hauled off the floor of the legislature after refusing an order by the Speaker to leave. He was then banned from the legislature for several months.

While Barrett had his detractors, his gregarious personality endeared him to many British Columbians, including those who normally wouldn’t vote NDP.

His likability was noted by Patrick Kinsella, a key strategist for Socred premier Bill Bennett, when he talked about political marketing to a group of Simon Fraser University students in 1984.

“Most of the things about a leader that you like, David Barrett was it. He was friendly. He had good relationships with the media. … He was frankly the guy that you would take to a Canucks game or take home to dinner. Bill Bennett, on the other hand, was perceived to be not a guy you would take to a Canucks game.”

Despite his personal appeal, Barrett lost to Bennett and Social Credit in three straight elections, in 1975, 1979 and 1983. After losing his seat in 1975, he quickly re-appeared in the legislature through a 1976 byelection.

Barrett appeared to have a strong chance of a return to power in the early stages of the 1983 provincial election. But his combative style backfired when reporters asked what he would do with the Socred fiscal restraint program if he became premier.

Barrett said he would phase it out as quickly as possible — a response that helped the Socreds define him as a socialist willing to use tax dollars to help his friends in the trade union movement.

Barrett would later write that he should have fudged his response and simply called for a review of the controversial program.

The youngest son of a fruit and vegetable pedlar, Barrett grew up on McSpadden Avenue, off Commercial Drive, in east Vancouver. His family was Jewish but his household was not religious.

There were plenty of socialists in his working-class neighbourhood, including his parents. His father, Sam Barrett, was a Fabian socialist and his mother, Rose Gordon, was a Communist who voted for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation.

He later recalled that as a child, he was in a parade protesting Fascist intervention in the Spanish Civil War. His parents split up just before Barrett’s 20th birthday.

After graduating from Britannia Secondary, Barrett went to Seattle University, a Jesuit school, in 1948. He graduated in 1953 and married Shirley Hackman shortly after his return to Vancouver that year. Their first son, Daniel, was born in 1954. The young couple later moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where Barrett earned a master’s degree in social work at St. Louis University.

Returning to B.C. in 1957, Barrett and his wife had two more children — Joe, born in 1956, and Jane, born in 1960.

Barrett worked at the Haney Correctional Institute as a social worker. Through his work there, he came in contact with CCF activists who persuaded him to seek provincial office.

At the time, civil servants were not allowed to run for public office, and in 1959, Barrett was fired from the prison when it became known he was seeking the CCF nomination in Dewdney.

A year later, he won the election and became an MLA for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, which later became the provincial New Democratic Party.

Barrett became leader of that party in 1969 and three years later secured the provincial NDP its first victory against the Socreds under W.A.C. Bennett.

Apart from creating the Agricultural Land Reserve and ICBC, he left behind important legislative reforms, including the introduction of question period in the legislature, and Hansard, an official record of legislative debate and proceedings.

His government also introduced French immersion in B.C. schools.

But some of his policies were deeply divisive and controversial, like the implementation of a mineral royalties tax, which inflamed the mining industry.

Barrett told a reporter in 1989 that none of the 367 bills passed while he was premier was radical. “None of the things we did, not one, was radical. Not one. And in the light of history that’s even more evident.”

After serving as leader of the Opposition in the B.C. legislature from 1976 until his party’s defeat in the 1983 election, he announced his resignation as leader of the provincial NDP.

He lectured for several years at some of North America’s top universities, including McGill and Harvard, and served a short stint as a radio talk show host, then returned to politics and ran successfully for the federal NDP.

He was elected as MP for the riding of Esquimalt-Juan de Fuca in 1988. During the race, he advocated a pro-choice view on abortion and improved child care services, including programs for street kids. His plan for Ottawa was to bring down the free trade agreement.

He held the riding until 1993, when he was defeated by Reform candidate Keith Martin.

He ran for the leadership of the federal NDP in 1989, losing narrowly on the fourth ballot to Audrey McLaughlin. His candidacy drew public attention to what several columnists called a “dull” race, with his critical views on Meech Lake, western alienation and a national obsession with Quebec.

After his departure from politics, he headed a public commission in 1999 investigating the leaky condo problem in Vancouver.

Barrett was made an officer of the Order of Canada in 2005 and named a member of the Order of B.C. in 2012.

In declining health in his final years, he withdrew from public life and spent them quietly with wife Shirley. He is survived by his wife and his three children.