PARKSVILLE — Graham Riches was teaching at the University of Regina in 1983 when the province opened its first food bank.

“I was curious because I had no idea what a food bank was,” he recalls. “They told me and I thought: ‘Well, that’s odd in the bread basket of the world and in a country with a well-developed social safety net.’”

Thirty years later, with food banks in every city and town, he now thinks it’s more than odd.

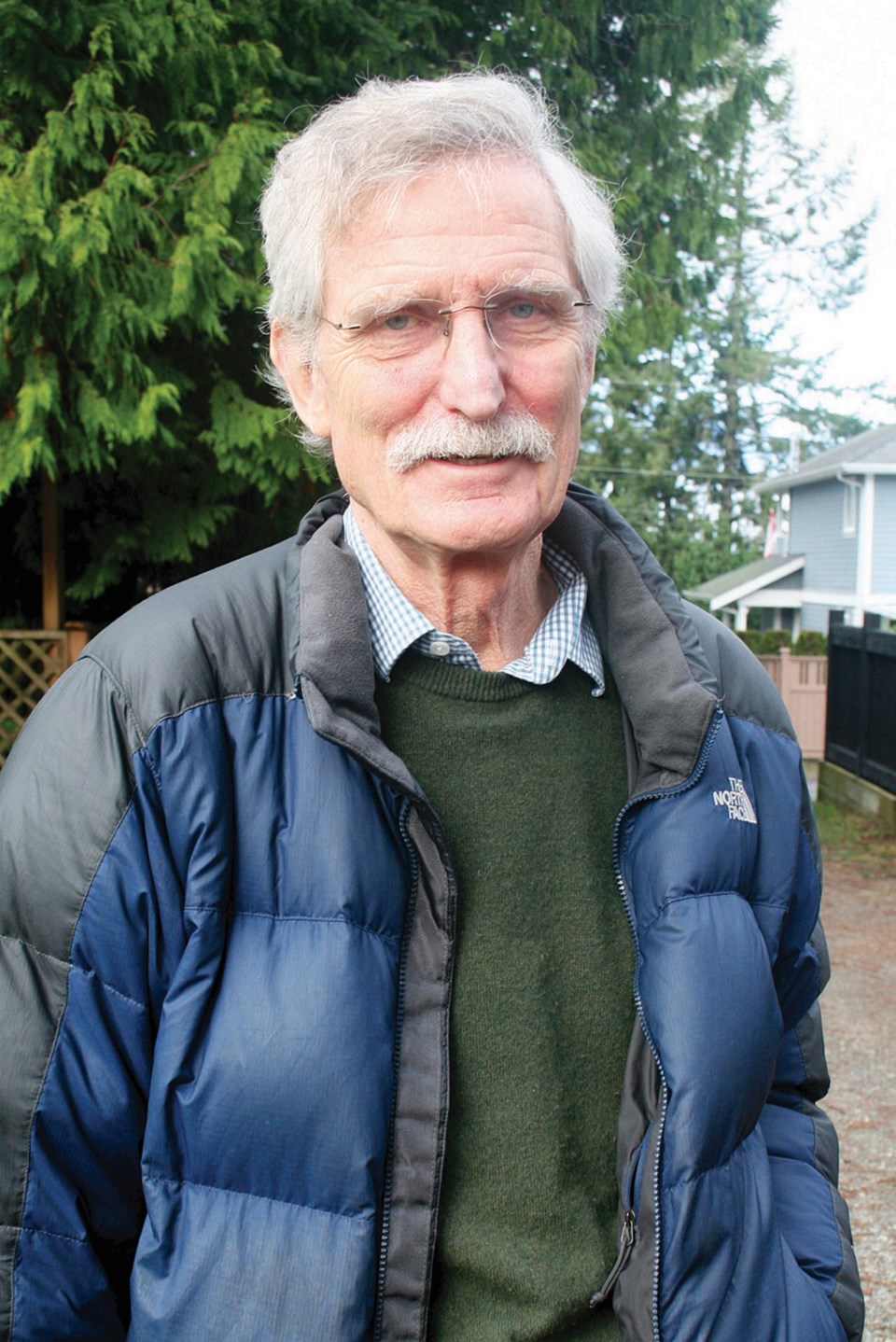

Riches, retired in Qualicum Beach as professor emeritus and former director of the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia, is one of the world’s foremost experts on hunger and the right to food.

With Tiina Silvasti, professor of Social and Public Policy at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, he has just published his third book on the subject: First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food?

The book, edited by Riches and Silvasti, examines the issue of food charity in 12 food-secure nations: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Estonia, Finland, Hong Kong, New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, the U.K. and the U.S.

In the 1960s, when Riches began lecturing in the field of social work at the University of Hong Kong, there was “a big debate” in the U.S., he recalls, on whether hunger and poverty should be addressed by providing income security — a social safety net — or by providing in-kind relief, that is, if you’re out of food, you get food stamps or food donations.

Nations such as Canada and the U.K. provided income security.

The U.S. chose the in-kind route, with the first food bank opening in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1967.

In the midst of a deep recession, Canada’s first food bank opened in Edmonton in 1981, led by Gerard Kennedy, later a contender for the leadership of the federal and Ontario Liberal parties. B.C.’s first food bank opened in 1982.

Riches subsequently travelled the nation talking to people about the phenomenon, resulting in his 1986 book, Food Banks and the Welfare Crisis.

He appeared on the Fifth Estate with Hana Gartner exploring the question: Will these food banks become permanent?

We know today that not only are they permanent, but the working poor and those on welfare increasingly rely on them.

“Why do we need food banks when we have employment insurance, pensions, social assistance?” Riches asked.

This question led to his 1997 edited publication, First World Hunger; Food Security and Welfare Politics, which focused on Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.

In Health Canada’s 2011 Canadian Community Health Survey, 3.9 million Canadians — 11.6 per cent of the population — said they are food insecure, an increase of 450,000 people from 2008.

“The problem with charitable relief is that the longer term problems of food insecurity aren’t being addressed,” said Riches. “People cannot afford to put food on the table.

“Food banks give the impression that the problem is being addressed,” he said, “but food poverty is still growing. It’s not a problem of food supply. It’s a problem of lack of income.”

Under international law, the government of Canada has an obligation to provide for its citizens, he said. It has ratified the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which includes the rights to food and an adequate standard of living.

However, Riches said, Canada has stopped short of embedding the covenant in its own laws, which would give it the force of domestic law.

Instead of living up to their legal obligations, he said, governments “exploit the religious context of giving, a moral imperative to feed the hungry.

“Hunger is today seen as a matter for charity,” he said. “It allows governments to look the other way.”

It also absolves wealthy food corporations, he said, noting the irony in Walmart, which is in the grocery business, making donations to food banks, which are then used by its low-paid employees.

Such a system, he said, creates “a secondary food market with secondary consumers. People are forced into public begging.”

Giving people “the scraps off the table,” he said, “is profoundly unethical.”

What the First World’s hungry really need, he said, is a living wage, adequate income security, affordable housing and, in the case of Canada, an affordable national childcare system.

“It comes back to the right to food,” said Riches. “It is something we must fundamentally address.

“Do we have a collective right to water? To air? It’s not just something we can leave to the happenstance of charity.”

Nations such as Canada have enough money to provide for their people, he said, but the approach to government of privatizing, of cutting taxes, of cutting services, of “let’s leave all this to the market,” has been “a 30-year failure.”

Canadians, he said, need to have a discussion on: “What’s the role of government in relation to domestic hunger?

“I bring it back to the right to food. It’s a question of human dignity.”