If anyone sounded the whistle warning that the Johnson Street Bridge was about to lift, Peter Reitsma didn’t hear it.

If anyone sounded the whistle warning that the Johnson Street Bridge was about to lift, Peter Reitsma didn’t hear it.

He was high in the superstructure, burning off old paint and rust with a propane torch. “I was between two panels of steel with the burner going crazy. I didn’t hear a thing.”

That’s how, 65 years ago, Reitsma ended up dangling high in the air, hanging on for dear life.

As Victoria’s Blue Bridge saga finally nears its end, this is part of the history that few ever knew and fewer still remember.

Reitsma won’t forget it, though. At 91, he’s still afraid of heights.

The tale goes back to 1953, the year after Peter and Tina Reitsma, married all of two months, left the Netherlands for Victoria.

He took whatever jobs he could, eventually landing with the City of Victoria, which is how he found himself high in the metalwork, preparing the bridge for a new paint job.

There were no safety harnesses in those days. No hard hats, no masks, no cranes or scissor lifts to carry workers aloft. Just grab the blowtorch, clamber up top and start burning away the old paint.

Every so often, the bridge had to be raised to let ships pass. When that happened, an alarm would sound and the workers would make for a “safe platform” — an immovable part of the span.

Sometimes, Reitsma’s location and the noise of the blowtorch would make it impossible to hear the warning, so someone would tug on a gas hose as a signal to come down.

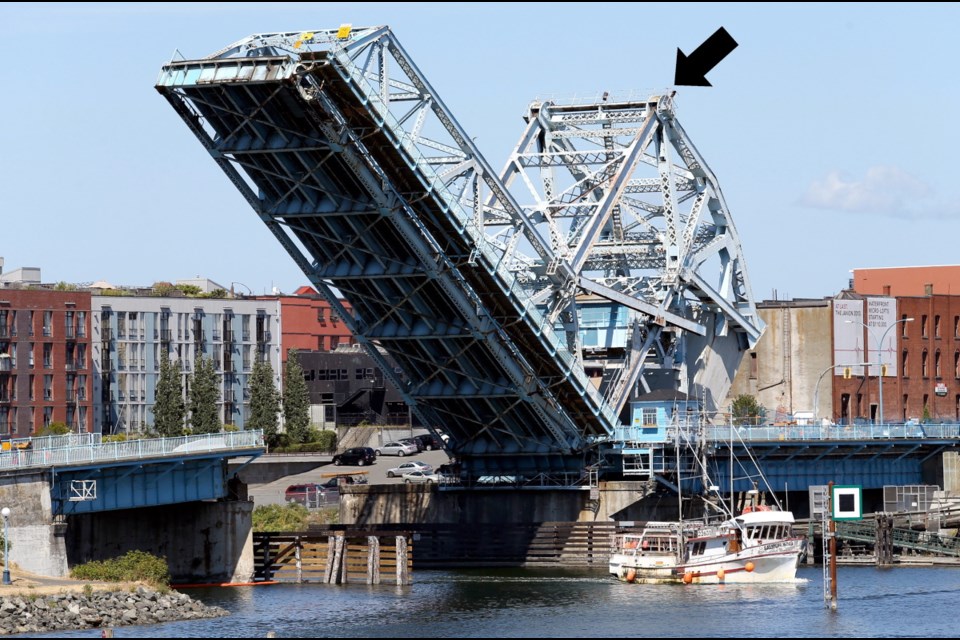

But that didn’t happen on the day in question. Reitsma was working at the very top of the bridge when, without warning, it began to move. All he could do was hang on, hoping that it wouldn’t open fully.

No such luck. A really tall ship was passing through. The bridge went all the way up.

Reitsma found himself suspended in the air, held by nothing but a metal brace across his lower back. He dropped the still-burning torch.

“The only thing I could do was press myself against the two sides, the plates.”

Heaven knows how long he was up there. Fifteen minutes? Twenty? Half an hour? “I cannot say how long it was, but it was a long time.”

What did he think of? Nothing. He was just trying to live — though to this day he firmly believes he had unseen company: “Angels. I’m sure they helped me there. There was no other way I could survive.”

When the bridge was finally lowered, Reitsma scrambled down. “I said: ‘Why didn’t you call me?” No one had a good answer to that. “The foreman said: ‘You can go home.’ It was 4 o’clock anyway.”

Reitma’s colleagues were surprised when he showed up the next morning. “I’ve got to work,” he said with a shrug. “Got to put bread on the table.” They let him toil at ground level after that.

As far as he knows, the incident was never reported. No one even asked how he was. Reitsma moved on to another city job, laying pipe for the water department, then went to work for a Happy Valley Road chicken farm.

Eventually he struck out on his own, first as a carpenter, then a building contractor. Peter Reitsma and Son Construction remains a going concern, though it’s the son and grandson running the show now.

As the years passed, the experience on the bridge stayed with Reitsma. On construction sites, he didn’t like going on roofs or walking on floor joists. “Still, today, I stay down close to earth,” he says.

Reitsma lives in a Saanich house surrounded by his own artwork — handcrafted furniture, beautifully rendered pencil sketches, landscape paintings, examples of traditional Hindeloopen decorative art from Friesland in the Netherlands.

Friesians are stubborn, he says. That helped him on the bridge, helped him get a toehold in Canada, helped him when the Germans invaded in the Second World War. When the city of Breda was evacuated, 14-year-old Reitsma, carrying his possessions in a couple of pillow cases, came across dead Dutch soldiers on the road, was forced to dive into ditches when the German planes came. During the war he ducked the raids in which young Dutchmen were snatched up for forced labour in Germany.

Then came the day in April 1945 when, perched on a rooftop, he watched Canadian aircraft strafe German positions. Then came the Canadian soldiers in their unfamiliar uniforms, sharing their chocolate bars and cigarettes. Then came his own life in Canada, a good life — though he could have done without that day atop what he still calls “my bridge.”