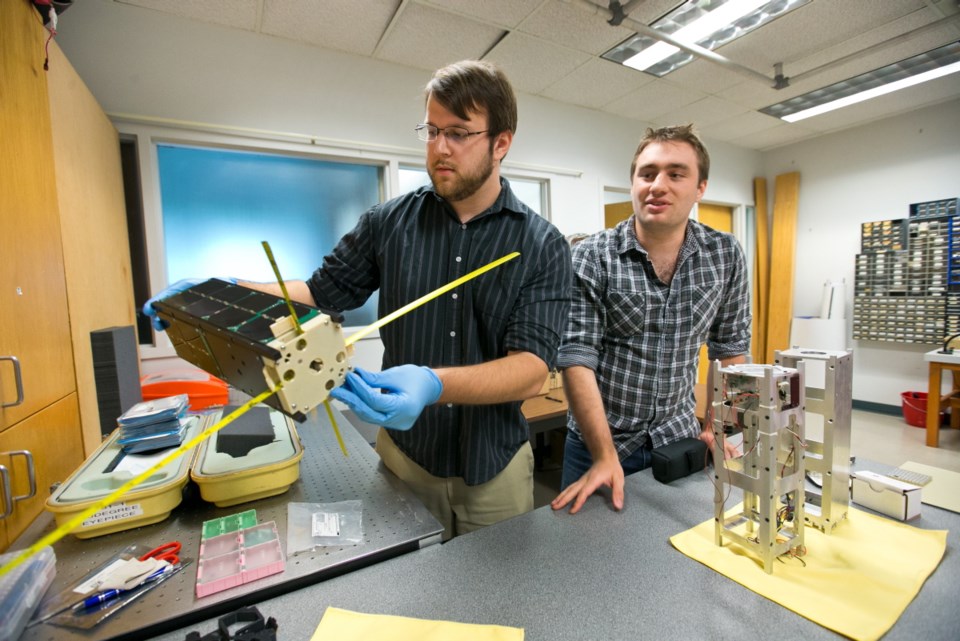

A tiny satellite about the size of a shoebox has earned a team of University of Victoria engineering students a prestigious national award that will help them launch their project — and their careers — into orbit.

The university’s ESOSat club won the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge, beating out five other universities with their nanosatellite.

“We’re very excited. There’s still quite a bit of work to do and testing verification, but we’re confident it’s going to work perfectly and exactly as we expect,” said Cass Hussmann, a master’s student in mechanical engineering and the project’s chief engineer.

The six finalists had to prove their satellites could withstand the harsh environment in space by undergoing vibration tests at the Canadian Space Agency’s David Florida Laboratory in Ottawa at the end of May.

The students incorporated a material called pyrolytic graphite and high-powered lasers that could allow the satellite to be manipulated using magnetic fields, said Devin Pelletier, a third-year electrical engineering student who is project manager. That could lead to breakthroughs in new forms of space travel and more efficient control systems for spacecrafts.

“The problem right now with spacecraft is most of the control systems are based off of fuel ejection or mass ejection,” Pelletier explained. “It’s pushing a little bit this way to push you in the other direction. The problem with that is you’re very limited in the amount of fuel you can carry. With this material and the fact that you only have to use lasers to control it, we can basically generate the energy from the sun, which is why [the satellite] is covered in solar panels.”

The students will also analyze the pyrolytic graphite’s ability to shield radiation.

“It could be a good lead for long-term space travel — let’s say going to Mars. It’s a big problem; people get a lot of radiation [exposure],” Pelletier said.

The satellite would also be an OSCAR, or an orbiting satellite carrying amateur radio, meaning that it’s open for communication with the amateur radio community.

The satellite took a team of about 20 students three years to design and hundreds of thousands of dollars in sponsorship to complete, including a $50,000 grant from UVic and $30,000 from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

The project was overseen by Afzal Suleman, a professor with the mechanical engineering department and Canadian alumni of the International Space University.

Pelletier also said Jim Harrington, owner of Esquimalt-based high-tech manufacturer A.G.O. Environmental Electronics, provided all the patented technology and specialized equipment to build the satellite.

Building a low-cost satellite included a lot of improvisation, including using two pieces of measuring tape for the cross-shaped antenna instead of buying much more expensive spring steel. Students also built their own circuit and battery boards, which earned them big points with the judges.

“A big part of our selling point is we designed all these ourselves,” Hussmann said.

Competitors had to meet design parameters. As one example, the cube satellite could be only 34 centimetres tall and 10 by 10 centimetres wide.

Larry Reeves, the founder of the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge, will help the students with the biggest challenge: finding a launch provider to rocket the cube satellite into orbit within the next year or two so that the team can start running experiments.

There are no Canadian companies, so the team is looking to Japan, Russia, India or the European Space Agency.

Winning the competition also means the team will get up to $10,000 to build a ground station on top of the engineering building to communicate with the satellite as it orbits 800 kilometres above the Earth.

“Up there we’re going to have a couple of antennas that can basically change direction to follow the satellite as it passes over UVic or the general area,” Pelletier said. “From there we’ll have a large computer transmitting and receiving information from the satellite as it passes over us.”

The students did all the work on top of their regular class commitments, which made for a lot of evenings and weekends in the lab, including a lot of 16-hour days in the two weeks leading up to the competition.

“Most engineers don’t have weekends,” Hussman said. “Or friends,” joked Pelletier.

But Pelletier and Hussman, who would both like to work in the aeronautics industry, say they hope the work will pay off when they graduate.

“If we can show something that we’ve all contributed greatly to [is] working in orbit, that definitely shows our capabilities,” Hussmann said.