Last week’s quarterly update on B.C.’s books included, for the first time, a look at the long-range prospects, and they’re not as rosy or buoyant as the short-term outlook.

Last week’s quarterly update on B.C.’s books included, for the first time, a look at the long-range prospects, and they’re not as rosy or buoyant as the short-term outlook.

The main structural elements of the economy are labour supply and productivity, and both are on a historic downward trend, mostly because of the aging population.

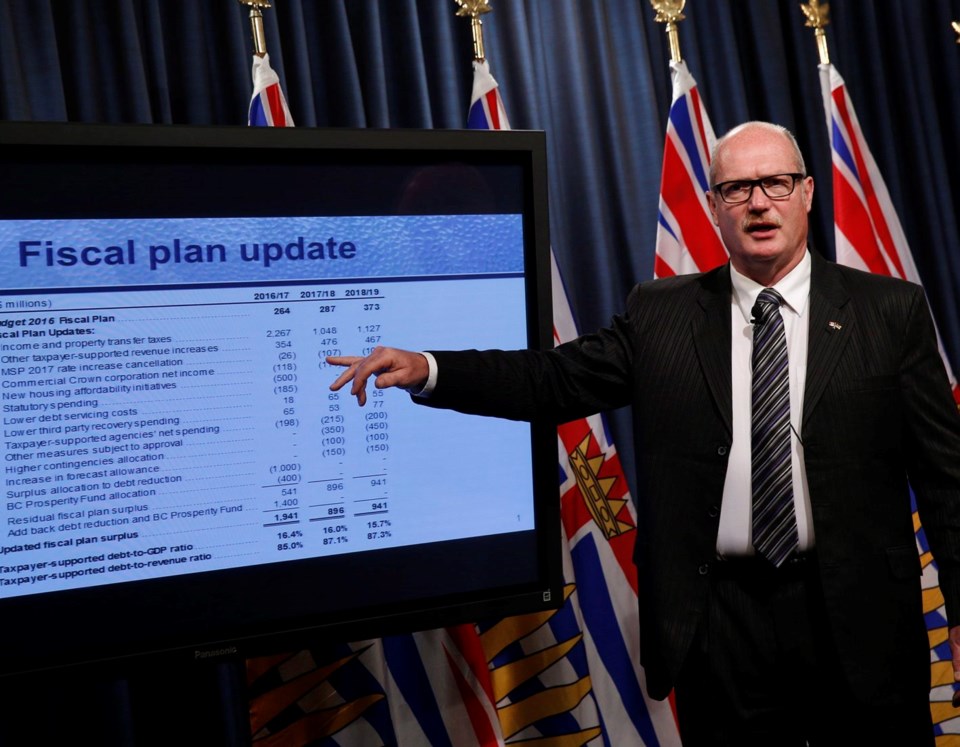

For all the wild revenue jumps reported in the quarterly update — an extra $965 million from the property-transfer tax, a surplus now seven times higher than expected in February — the long-range look predicts economic growth is likely to moderate, reflecting the aging demographics.

Finance Minister Mike de Jong said that’s already clear. “In the 1970s, if you weren’t realizing five or six per cent GDP growth, people wondered what was wrong. The new norm is probably somewhere between two and three per cent.”

The quarterly report is a snapshot of the first three months of the fiscal year. The budget covers a full year and the economic plan covers three years. But up to now, there hasn’t been much in the way of a forecast that tries to look 15 to 25 years down the road.

The four pages in last week’s report that attempt to do that are an initial effort to respond to a recommendation from the auditor general that B.C. do more to measure long-term fiscal sustainability.

That office reported in 2015 on the need to look further out, “for the same reason you look ahead while you drive a car or walk through a crowded market. You need to see far enough ahead to avoid hazards.

“And the slower you are to react and adjust, the further ahead you need to look.”

The main issue the analysts are seeing off in the distance is represented in one slide from the Finance Ministry’s presentation. It’s the percentage of B.C. population over 65. It was about nine per cent in 1972. It’s 17 per cent now, and the forecast shows it rising to 25 per cent by 2035.

That’s been a fact of life in economic forecasting for years, covered ad nauseam by everyone. The trend is not in dispute — it’s what to do about it that’s the issue.

Population growth has slowed in B.C. over the past 50 years, from three per cent a year in the early 1970s to one per cent more recently. It’s mostly because of falling fertility rates, only partly offset by moderate net migration. The picture is the same in many other economies.

At the same time, people are healthier, living longer than ever and with better lifestyles. It’s conceivable now that older people can spend more time retired, living on pensions, than they did working.

Add in the 20-year baby boom after the Second World War, and the aging trend is even more obvious. B.C. Stats projects the growth in seniors to outstrip the growth of children and adults, with the annual overall population growth to drop below one per cent by 2035.

“Slowing growth of the overall population limits the possible rate of growth of B.C.’s labour supply,” said the Finance Ministry report. It said only 13 per cent of seniors work. Youth labour-force participation has declined over time because of emphasis on post-secondary education. Hours worked per employee have trended down, as part-time work increases.

And there is evidence professionals are working less because of more emphasis on work-life balance.

“These long-term trends point toward continued slowing in B.C.’s labour supply in the coming decades.”

The report has a parallel section on a historic decline in productivity, but said the specific reasons are unclear.

De Jong said after scanning the numbers, “you quickly begin to realize there are some fairly serious pressures facing us as a society.”

The report said slower growth isn’t inevitable. Changing circumstances force adaptation, so a labour crunch could force wages higher and motivate more people into work. Wholesale immigration could bolster the workforce, and innovation could boost productivity.

But the prevailing view is that the growth curve will continue lower than in the past.