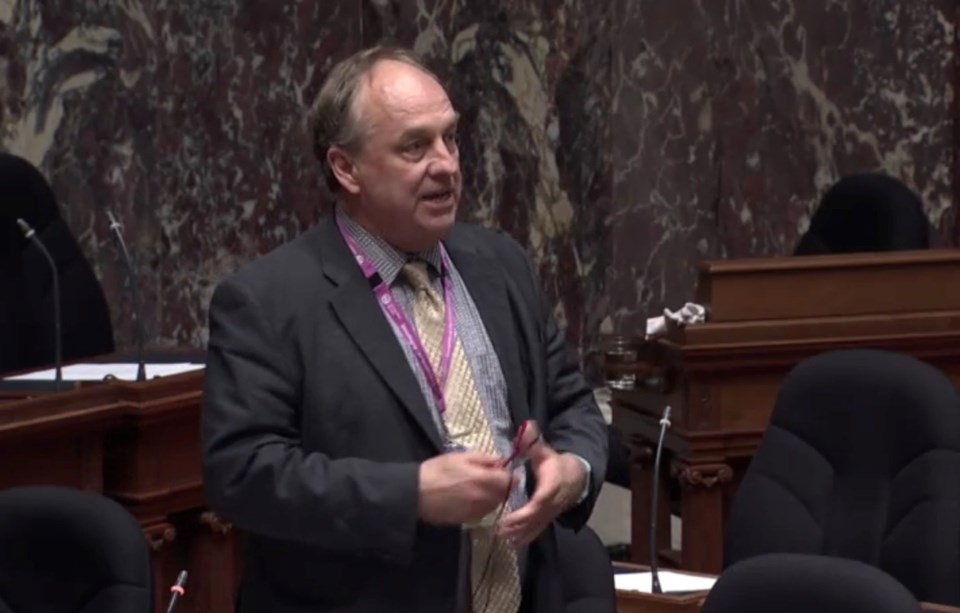

Last week, the talk of the legislature was B.C. Green Party Leader Andrew Weaver.

In many ways, Weaver is the most interesting person in Canadian politics. Set aside his impressive credentials and pedigree, or his bizarrely fascinating nap habits, as described in Rob Shaw and Richard Zussman’s book A Matter of Confidence.

He’s in a unique situation: Not really in government; not really in opposition; the first Green leader at any level in Canada who has had to manage a caucus.

After the election, Weaver was thrust into a once-in-a-lifetime role as kingmaker — an unimaginably heavy responsibility, not least because Christy Clark and John Horgan offered two very different paths. No matter how you feel about his choice, he took his role seriously. The responsibility must have weighed on him — as I’m sure does his portrayal across the Prairies and much of the national press as a postmodern Lady Macbeth.

It’s difficult to describe his actual, facts-on-the-ground role in this legislature. No, he’s not in government. But he’s vastly more important and influential than your typical NDP backbencher, and probably much of cabinet, not least because his threats to bring down the government are both credible and plausible.

Finally, with three seats and less than 17 per cent of the vote, he’s a living, breathing embodiment of the biggest arguments both for and against proportional representation — a small party dictating terms to a much larger one.

That’s a lot of scrutiny for a guy from Oak Bay. But as interesting as all that is, it’s not what got people talking.

On Tuesday afternoon, Weaver missed his chance to propose amendments to a bill, and very publicly lost his temper. It stayed lost for a good long while.

There’s no getting around why: He was late. Seven minutes late, to be exact.

There are no do-overs in the legislature. Once a window closes and moves on to the next stage — in this case from committee stage to third reading of a bill — that’s it. It’s an MLA’s job to be there on time, or ensure someone else from their party is. Full stop.

He didn’t blame anyone for being late. But he was astonished that the legislature carried on without him. He demanded resignations, and singled out the B.C. Liberals for “petty political games,” though, you might recall, they no longer control the business of the legislature.

Weaver says he discussed his proposed amendments with several B.C. Liberal MLAs, who then should have somehow hit pause or asked holding questions on his behalf until he arrived.

You might think that’s reasonable. But if I wanted to ensure my party was represented in the house, my first choice would be my two colleagues, one of whom is whip, the other house leader, both paid extra for the privilege. Failing that, I might choose the party that actually controls the legislature, the same one I signed a public pact to support and make into a government.

Instead, Weaver assumed the party with the least control, and whom he had insulted less than two hours previously, would act unbidden on his behalf.

(For the record, the insult was calling the B.C. Liberals the “Liberal Party of Alberta.” He was forced to withdraw it.)

Two additional details make this interlude even more bizarre. First, the bill wasn’t contentious; nobody voted against it. Even stranger, it appears Weaver’s amendments would have been out of order. It’s complicated, but basically the rules state members can’t propose amendments to a government bill that substantially changes the spirit of the bill, or would mean spending additional money.

In other words, he showed up too late to introduce changes he couldn’t suggest to a bill he supported.

Much ado about nothing, indeed.

If nothing else, this episode provides insight into one of the strangest aspects of the legislature — in an adversarial system, members (and staff) from different parties work against each other, but they also share a unique and special workplace. In a strange way, they’re simultaneously opponents and colleagues.

It’s a roller-coaster. And that’s why, in the space of less than three hours, Weaver found himself going from having to withdraw an insult to expecting the same people to act as his agent, and back to insulting them again.

Maclean Kay was former premier Christy Clark’s speechwriter for five years.