From time to time, those who work in public health are accused of being biased — and it’s true.

In spite of the urgings of some — usually from the corporate or neo-liberal world — that public-health officials be neutral, that is not their job. They are and should be biased in favour of health, and biased against anything that harms health — be it government policies, corporate practices or individual behaviours. For that, we should be glad.

That is not to say that public-health assessments of potential health hazards are biased — they are not. Public health begins with an objective assessment of the evidence as to possible harm to health from whatever it is that is of concern. If the conclusion is that it is not a health hazard, then no action is taken.

But if there is an assessment that something is harmful, public health is duty-bound to do something about it, based on an assessment of the severity of the problem. Is this a minor problem, something that affects only a small number of people and has only short-lived and non-life-threatening effects? Or is it a major problem, one that affects many people and has potentially serious, even life-threatening consequences? Most often, it is somewhere in between.

The challenge, of course, is that often there is incomplete or insufficient evidence to come to a definitive answer. But that is understood and indeed an approach to dealing with uncertainty is even written into law.

For example, B.C.’s Public Health Act states: “A health officer may issue an order … only if the health officer reasonably believes that a health hazard exists,” and there are numerous other places in the act where it is clear the reasonable belief of a health officer is sufficient reason to take action.

Ontario’s Health Protection and Promotion Act is even broader, stating in numerous places, regarding numerous situations, that: “A medical officer of health or a public-health inspector may [take some form of action] where he or she is of the opinion, upon reasonable and probable grounds,” that there is a health hazard of some sort and that action is needed to reduce or eliminate it.

Note that public-health officers are expected to form an opinion, and there does not have to be definitive proof, just “reasonable belief” or “reasonable and probable grounds” to act to protect the health of the public.

This is, in effect, a codification of the precautionary principle, which was defined as follows in the 1992 Rio Declaration of the Earth Summit: “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

This principle is in a number of international treaties to which Canada is a signatory, and is one of the guiding principles in the 1999 Canadian Environmental Protection Act, which the government has the duty to administer — although how well it is implemented is debatable.

I can think of very few cases in a 40-year career in public health where the hazard to health turns out to be less than expected; it almost always is worse. Which is why public health must be biased in favour of protecting the health of the public, and be guided by the precautionary principle.

Almost inevitably, this brings public health into conflict with powerful forces, be they private corporations interested in making money, or governments implementing their policies — or, more often, declining to take action in the face of a threat, especially if that threat comes from a powerful corporation that is a supporter, funder or ideological partner.

That is why both these powerful forces want public health to be neutral; just stick to the facts, don’t have opinions, don’t act until you have definitive proof, don’t speak out. The problem is that too often, definitive proof comes a bit late, in the shape of dead, sick or injured citizens.

So, as citizens, we should be glad of and support strong and independent health officers, acting in the public interest, biased toward health and applying the precautionary principle. We must not let governments weaken our protectors and thus our health.

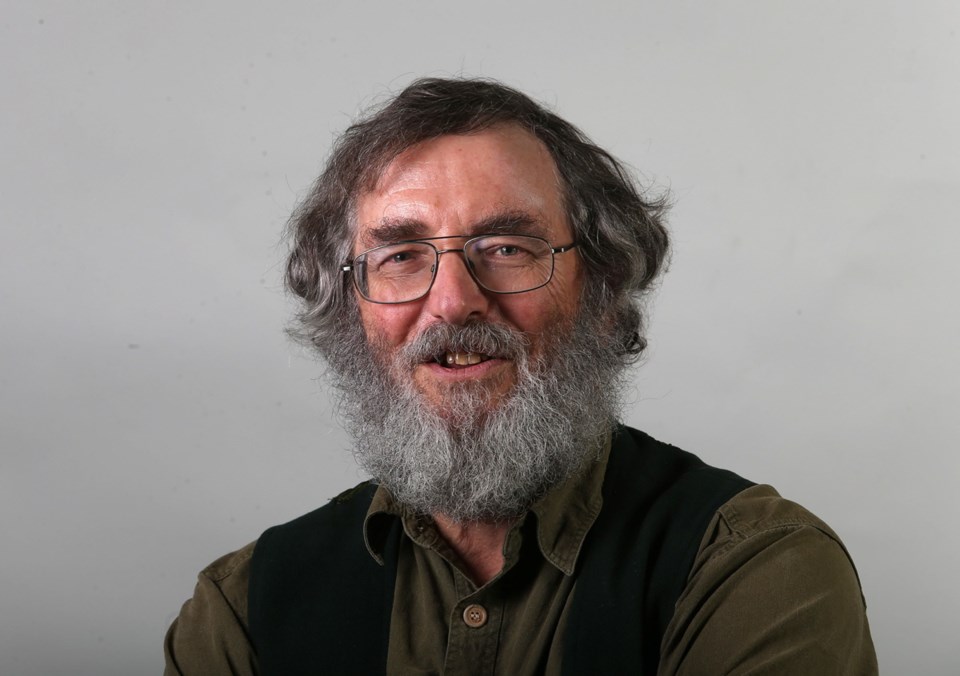

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s school of public health and social policy.