The following is excerpted from The Graveyard of the Pacific: Shipwreck Tales from the Depths of History, by Anthony Dalton.

It’s not often that one comes across mention of military vessels in the tales of shipwrecks in the notorious Graveyard of the Pacific. Yet a few British, American and Canadian naval ships have met disaster in this dangerous region.

On either Dec. 2 or 3, 1901, Britain’s Royal Navy lost HMS Condor somewhere off Tatoosh Island. Condor was hit by a hellish storm soon after leaving Esquimalt, bound for Hawaii. She was a steel sloop of war built on the Thames estuary only three years before. Stationed on Vancouver Island for a while, she was acknowledged to be fast and extremely seaworthy. In the cold, wet and windy winter of 1901, her complement of 130 officers and men, and possibly 10 naval cadets, would have been looking forward to their time in the tropical sun.

The 180-foot-long ship, powered by triple-expansion engines and aided when necessary by auxiliary sails, raced out through Juan de Fuca Strait to the Pacific Ocean at the beginning of December.

Condor passed Tatoosh Island and left Cape Flattery light behind, signalling her farewell to the land. Late that night, one of the worst storms in living memory blasted the Pacific Northwest. HMS Condor, built to withstand extreme conditions, disappeared with every member of her crew and without leaving a trace.

Another Royal Navy ship, HMS Warspite, had left Esquimalt with Condor, but she delayed in the strait, apparently for gunnery practice. When she emerged onto the ocean in the aftermath of the storm, she met seas like mountains and high winds. Warspite suffered damage, but managed to weather the tempest. Had her captain not chosen to exercise his gunnery crews, she would almost certainly have joined Condor in a fight for survival against the elements or, at worst, descended to the seabed.

Another ship was in the area at the time that Condor disappeared. The 3,300-ton steel freighter Matteawan had been sighted passing Cape Flattery the day before the naval ship. Loaded with 5,000 tons of coal from Nanaimo, she also disappeared, leaving nothing to show where she went down.

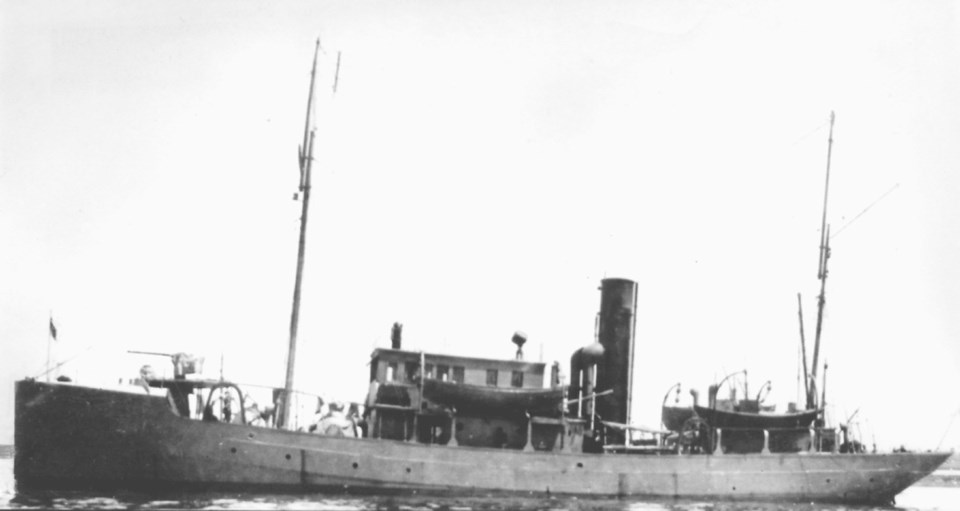

In the late 1920s, the Royal Canadian Navy owned a fleet of 12 battle-class steel trawlers. Four of them were employed as protection vessels for the Department of Marine and Fisheries, patrolling the coasts of British Columbia. One was named HMCS Thiepval. She was 130 feet long and 25 feet in width.

Thiepval was launched for the Royal Canadian Navy at Kingston, Ont., on the eastern end of Lake Ontario, in 1917. For the final months of the First World War, she worked off Newfoundland as a guard for trans-Atlantic convoys. Coal-fired, her maximum speed of 10 knots would not allow her to serve in any other capacity, although she did hunt U-boats without success.

In March 1920, she was loaned to the Department of Marine and Fisheries as a patrol vessel and sent to the West Coast by way of the Panama Canal. Thiepval’s first years in the Pacific Northwest kept her crew busy. She hit bottom near Prince Rupert in 1920 and did the same near Bella Bella a year later. She was lucky each time, getting away with a few scrapes and bruises and minor leaks.

At the tail end of the winter of 1924, she crossed the North Pacific to Hakodate, Japan. Her task was to place fuel and oil dumps for a round-the-world flight attempt by British military aviators. Squadron leader Stuart MacLaren and Flying Officer Plenderleith did not succeed in their attempt. They wrecked the airplane (a Vickers Vulture flying boat) that August at Nikolski, in the Komandorski Islands. Thiepval went to salvage the wreckage. That short stay made her the first Canadian warship to visit any part of the new Communist Russia.

Back in British Columbia after her foreign adventures, Thiepval took on the roles of fisheries protection vessel and lifeguard. Each winter, she and the others of her class went on three-week “Life Saving Patrols” along the west coast of Vancouver Island. She even rescued her sister ship HMCS Armentières, which hit a rock in Barkley Sound.

Between patrols, the crews laid over at Bamfield, so they were close and ready for action when required. Thiepval’s radio room was manned and operational 24 hours a day in case a ship needed assistance. In one rescue, she assisted the Mexican schooner Chapultepec by pulling her off a reef at Carmanah Point in 1926.

The waters of Barkley Sound claimed Thiepval when she was returning from a patrol under the command of Lt.-Cmdr. Harold Tingley. Heading for Bamfield in the early afternoon of Feb. 27, 1930, Tingley cut through the Broken Islands at near high tide.

As he had done before, he used a broad channel between Turret and Turtle islands. Running at nine knots, Thiepval was scored by a submerged but uncharted rock, and she was brought to a standstill. She sent out a distress signal, and HMCS Armentières raced from Victoria to help.

Tingley calmly went about the process of examining his ship. He stopped the engines and had all hatches battened down. Finding no obvious life-threatening damage, he tried to take her off using full astern power. The propeller lashed the water to foam, but Thiepval would not move. Tingley ordered an inspection of the ship from the water, having a boat lowered to cruise right round her. The report came back that she was sitting with her forward section lodged on a rock shelf. Tingley watched the rising tide, hoping it would help float her off. It did not.

When the tide changed and went on the ebb, the trawler’s position became potentially dangerous. She was listing so far that Tingley had the stokers shift coal from the low side of the ship to the high side. He had the crew take a cable across to Turtle Island and secure it there in an attempt to keep Thiepval upright. Close to 5 p.m., with the tide still on the ebb, the ship lurched to starboard at 45 degrees. Soon after, Tingley ordered his 21-man crew to abandon ship.

They rowed the short distance to Turtle Island and made camp for the night where they could continue to keep a watch on their ship.

Armentières arrived at daybreak, and the two crews witnessed a sad and sorry sight: Thiepval was laid over at 60 degrees with her stern underwater. Tingley and members of his crew, however, went back aboard the ship for another inspection and found the engine room flooded and the water rising to the mess deck. Accepting the situation was out of their control, Tingley ordered his shipmates to carry off everything of value. As they left, the sea was already beginning to flow over the starboard gunwale.

With no other option, the naval authorities sent for a salvage ship, aptly named Salvage King, but she did not get there in time. Long before the salvagers arrived, Thiepval lost her balance on the rock in the dark of night and slipped off into deep water, where she still lies.

The U.S. Navy lost one of its older troopships off Tatoosh Island in January 1972. The 11,828-ton USS General M.C. Meigs was under tow by the U.S. Navy tug Gear from Olympia, Washington, to San Francisco. A Force 8 gale blew in, hitting the tug and tow with high winds and big seas. At 3 a.m. on Jan. 9, the tow line parted west of Cape Flattery, and General M.C. Meigs was free, dangerous and in peril.

The tug and U.S. coast guard vessels worked together to harness the drifting 622-foot-long ship, but without success. While they stood by helplessly, the wind and waves carried the big grey ship to land until she struck a rocky ledge and broke in two, with the halves wrapped around a big rock pinnacle. She came to rest in full view of the mainland, only seven miles south of Cape Flattery. Her remains are there to this day.

© Anthony Dalton, Heritage House Publishing, 2010. heritagehouse.ca

Anthony Dalton is the author of several books on Canadian maritime history. He lives in Tsawwassen.