Artist Roy Henry Vickers is best known for his iconic imagery of aboriginal people. But ask him about his personal inspiration and he’ll tell you it’s stories.

“First Nations peoples, before the written word came, we learned by listening to stories and we learned by hearing songs, which are stories, and we learned by watching dances, which are stories acted out,” said Vickers in a telephone interview.

“So, to me, it’s not an accident that I am an artist,” he said.

“It’s a responsibility for me to use my artistic expression as a storyteller.”

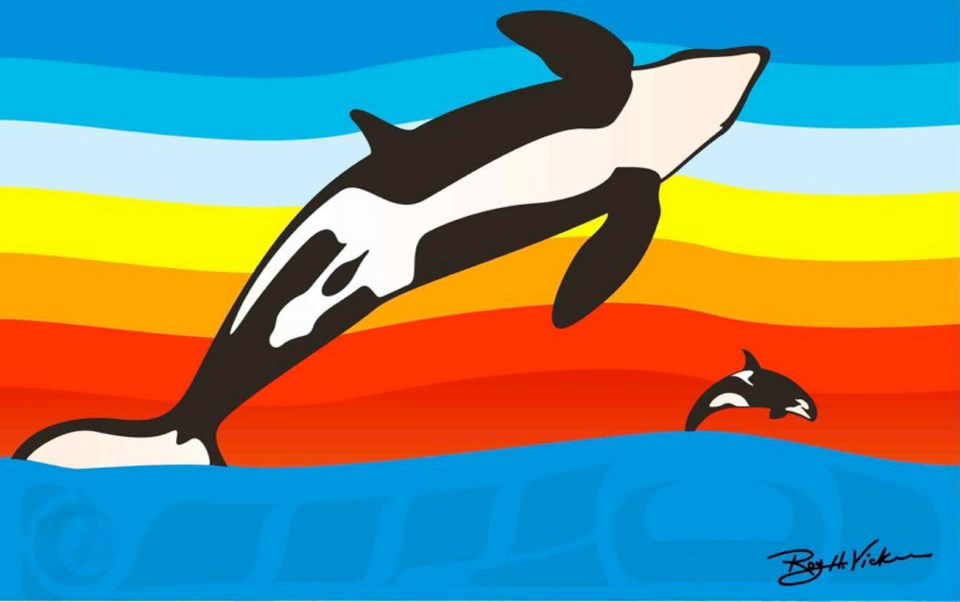

He and his longtime friend, Robert (Lucky) Budd, have just completed their third illustrated novel, Orca Chief, based on a legend told and retold and passed down. Budd and Vickers also teamed up to write Raven Brings the Light in 2013 and Cloudwalker in 2014.

Orca Chief is the story of a leader of the orca folk who told human beings of the ways of the sea, its tides and inhabitants, and the various kinds of salmon. It’s also the first time it’s ever appeared in print.

Vickers said it teaches all people about respecting the ocean and the creatures living in it.

Nobody has any real idea how old the story is although it’s believed to have originated with the Kitkatla people of the Tsmishian First Nation. Vickers said he first learned it decades ago from an elderly member of his family.

But Vickers said when Budd first suggested he put the stories in a book, he was reluctant.

“These are not books, these are stories,” he said. “I tell these stories, I don’t write them down on a piece of paper.”

Vickers said he even sat down at a computer or with a pen several times and tried to write them down but was unable to make the switch. Eventually, pressed by Budd, he came to believe putting the stories into books is likely the best way to see they are preserved and passed on. And Vickers said that is a responsibility all storytellers must acknowledge.

“We are responsible to the knowledge that is given to us,” Vickers said. “That responsibility is to give that knowledge to others, so they might know.”

His original problem, however, arose because he believes stories are meant for storytellers to recite, act out, sing and shout. They lose something precious and intimate in books.

For example, there’s the immediate back story. Good storytellers will begin by recounting when and how they were first told the tale. They will even announce that “now” would be a good time to tell it again.

So Vickers said when he first heard the tale of the Orca Chief years ago, a small rupture was afoot in the community that he still won’t name. People were upset over an attempt to claim a particular icon and make a profit from it.

“I was told, ‘This is not the time to be telling the story because it would cause great strife but one day you’ll be able to tell it,’ ” Vickers said.

“I didn’t know what that day was but now I do,” he said. “So now I can tell the story.”

Also lost are the metaphors and imagery of the First Nations language with its layers of sensation and images from the natural world.

For example, Vickers said if he asked his aunty if she has seen his carving knife, she might reply with something that literally translates to, “There are so many leaves on the ground I can’t tell which is which.”

Or, if he asks her if she knows a particular person she has never met, she will answer in a way that translates as, “No, he is not in my heart.”

“The language is incredibly poetic,” said Vickers. “And if we know the land and we know the ocean, then we can know the language.”

Also lost in a book are the personas of the storytellers themselves. A good storyteller will sing, perhaps dance or shout and make expressions. Sometimes the songs will be in a language listeners don’t even know. But that’s OK.

“When you are singing, people are feeling you as well as hearing you,” said Vickers. “They might not be able to understand what you are saying but they sure can feel what you mean.”

He said, however, that by working together, he and Budd were able to translate Orca Chief into a modern book.

Budd, who has a background in history and has done work with CBC archives, said he considers his role with Vickers as less as a co-author and more of a producer.

He said First Nations storytellers often include pieces of narrative that arise almost separately from the main story. It’s just part of the way stories are told in the tradition. But including them can disrupt the narrative arc of an English book.

“A lot of the time there is tangential stuff that happens when you tell a story and it’s all lovely and good,” said Budd. “But it doesn’t really translate into a book.”

“Culturally, it comes from a different tradition than a lot of the stories people are used to,” he said. “Tangentially, things will just happen and you have to just accept them and move on.”

Certain elements of timing and narrative in Orca Chief might be out of place in standard English. But it’s all part of the original story and very special.

So Budd said he started breaking the Orca Chief story down into smaller pieces or moments. He would then ask Vickers if had any particular image in mind for this moment of the story to illustrate the book.

Piece by piece the story comes together in a way that is not the same as a personally recounted tale. But it ensures the images, lessons and tales can be passed along and appreciated.

“These stories have been told for thousands of years and with any kind of luck they will be told for thousands more,” said Budd. “We are just one link in that chain.”

Orca Chief is published by Harbour Publishing. Vickers and Budd will be in Victoria to speak about the book on Thursday at 7 p.m. at Legacy Art Gallery, 630 Yates St.