The American photographer and ethnologist Edward Curtis spent almost 30 years compiling a 20-volume work documenting the vanishing traditional world of the native people of western North America. In Edward S. Curtis Above the Medicine Line, Victoria author and publisher Rodger Touchie delves into the years Curtis spent from 1909 to 1924 studying the tribes of the British Columbia coast, whom he considered among the most fascinating he encountered.

There were immediate clues in the introduction to Volume 10 that this ambitious undertaking went well beyond the substantial accomplishments of its nine predecessors. In Volume 9, Curtis had done a masterful job of representing the culture of the Salishan linguistic group and the coastal tribes in the most southerly quarter of the North Pacific coast.

As for the scope of study in the North Pacific, he wrote: “The inhabitants of this thousand-mile coast belong to several linguistic stocks and spoke a very large number of dialects … Many tribes were squalid hovel-dwellers, as poor in tradition and ceremony as in material wealth; others were comparatively rich in property, powerful and aggressive in warfare, and possessed of an abundant mythology and an intricate ceremonial system.”

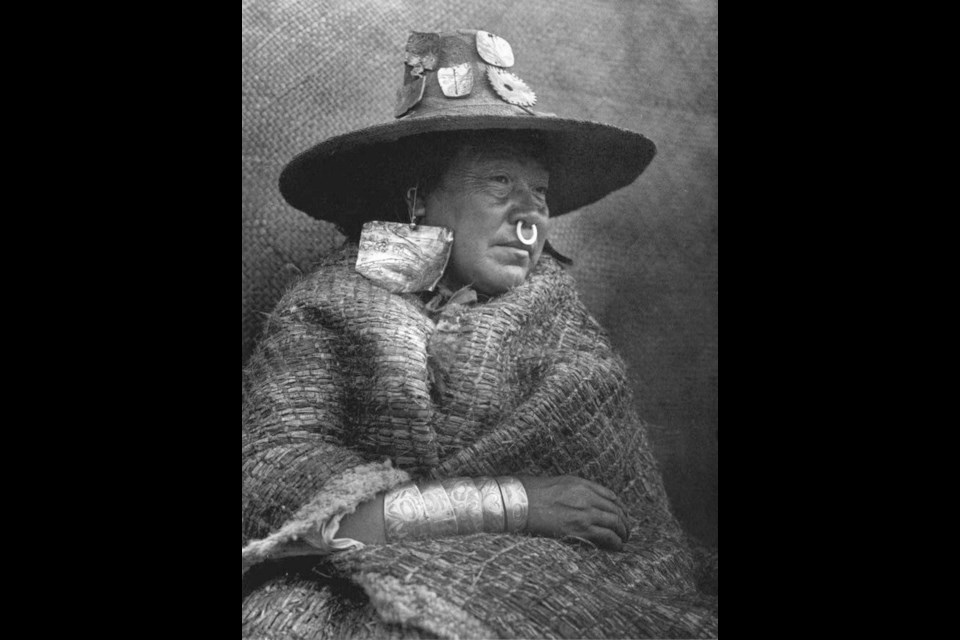

Curtis’s discovery of the Kwakiutl and his ensuing fieldwork are, in a sense, the apex of the entire project. By then, he had worked for a decade trying to recapture the glories, integrity and nobility of aboriginal peoples, who had suffered in many ways from the arrival of what called itself a civilized culture. He had supplied wardrobes, recreated settings, staged re-enactments, touched up photographs and used every technical trick he could muster to replicate a way of life that was largely gone. Visions of a lost heritage were reflected in the eyes of many of the subjects of his early 20th-century portraits.

For Curtis, a student of ethnology, the Kwakiutl were unique and fascinating.

“Of all of these coast dwellers, the Kwakiutl tribes were one of the most important groups, and at the present time theirs are the only villages where primitive life can still be observed.” Today, it is more accurately recognized that Kwakiutl is the name of the specific people of the Fort Rupert area, while the larger group that anthropologists referred to as Kwakiutl are the Kwakwaka’wakw, a term that means “Those who speak Kwak’wala.”

Ironically, Curtis was now in the lands that had inspired Dr. Franz Boas to study and publish The Social Organization and Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians in 1897, thereby gaining status at Columbia University, where he founded the anthropology program. Boas, then ensconced at Columbia, had been an early skeptic when it was announced that J.P. Morgan would back Curtis’s project. He had triggered a rumour mill that had worked against Curtis in his fundraising efforts and almost sabotaged the entire project. Now, as Curtis neared the halfway point of his 20-volume undertaking, he stated in his introduction to Volume 10 that “the research for this volume was greatly simplified and made more effective by the very complete work of Dr. Franz Boas.”

Part of the specific appeal of the Kwakiutl as a study group was that they lived between peoples that bore contrasting cultural traits. To the north, the Haida, Tlingit and Tsimshian were matrilineal, as opposed to the patrilineal nature of the Nuu-chah-nulth and Salishan peoples to their south and west.

Also, unlike other cultures Curtis had studied (including his own world of capitalism) where status was measured by wealth, the Kwakiutl achieved status based on the amount they gave away and the elaborate potlatch ceremony that highlighted this activity.

The richness of Curtis’s study was the result of one man: George Hunt. “Not the least value of this collection of data lies in the exceptionally intimate glimpses into certain phases of primitive life and thought” that Hunt was able to facilitate. When Curtis met him, the Métis son of a Tsimshian mother and a Hudson Bay Company employee had spent 60 years among the natives, largely Kwakiutl, around Fort Rupert. “He has so thoroughly learned the intricate ceremonial and shamanistic practices of these people, as well as their mythological and economic lore, that today our best authority on the Kwakiutl Indians is this man, who, without a single day’s schooling, minutely records Indian customs in the native language and translates it.”

Perhaps Curtis’s least-acknowledged quality was his ability to gain the trust of informants. He was thus able to record sincere commentary and bequeath valuable cultural information that has served aboriginal communities and all interested historians. For example, it has been widely recognized that abalone shells of high lustre and substance were cherished as ornaments, not only by the Kwakiutl, but by the Cowichan and other southern Salishan peoples as well. While many have assumed that they originated on the British Columbia coast, Curtis revealed the true origins of the highly polished shells.

“It is related that about 1840 a Tsimshian man sailed to Oahu, Hawaii, aboard a trading ship on which he frequently served as pilot. When he returned he brought large boxes of large abalone-shells, which he sold among the northern tribes, whence many of them were obtained by the Kwakiutl.” This enlightenment came from Curtis’s primary source, George Hunt, who was describing the entrepreneurial exploits of his grandfather.

Curtis also sheds light on the history of the most iconic of West Coast aboriginal symbols, the totem pole. Today, it is common for pictorial documentation to focus on the imagery of house-post and totem carvings as if they date back through centuries of evolution. Yet Curtis suggested that their introduction to the Kwakiutl village was as recent as the 19th century.

He stated: “As late as 1865, carved posts were by no means numerous, and the original of each was believed to have been given by some supernatural being to the ancestor of the family.” Deducing how things had evolved, Curtis concluded: “Carved posts have become increasingly common, the authority to make use of some certain house-frame being one of the most valuable rights transferred in marriage.”

The role of the warrior in Kwakiutl society was paramount. A Kwakiutl war party, the Lekwiltok being the most feared, included the warrior (papaqa, merciless man), the “watcher,” the “burner” and the “plunderers,” as well as the “canoe guard.” When the warrior went into battle, he “carried about his neck a small bundle of cedar withes — his ‘slave ropes’ — on which to hang the heads … he hoped to secure.”

Hostilities had been a part of the culture for centuries, so it is no surprise that the arrival of white traders simply meant new targets for the Lekwiltok. Even when Curtis did his research in Puget Sound, the name of this tribe was still uttered with hate in Salish villages. One Lekwiltok informant told Curtis that if he were “to search the little bays between Cape Mudge and Salmon River, the charred remains of a surprising number of schooners would be found.”

Today, the Lekwiltok are better known as the Southern Kwakiutl people. In their own Kwak’wala language they are called the Laich-kwil-tach people of Quadra Island and Campbell River.

Edward S. Curtis Above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West © Rodger D. Touchie, Heritage House Publishing