The Mary Winspear Centre in Sidney has four handsome Salish totem poles flanking its front door, the work of local masters Charles Elliott and Doug Lafortune. Inside, the spacious foyer (also known as the Myfanwy Pavelic Gallery) features lovely display cases that hold two large stone carvings by Mohawk artist Michel Beauvais. And during this month you’ll see masks by Kevin Cranmer of Alert Bay, prints by Richard Hunt of Victoria and carvings by Chaz Elliott of Brentwood Bay. All this leads the way to the sixth annual invitational exhibition of First Nations, Inuit and Métis artists.

The Mary Winspear Centre in Sidney has four handsome Salish totem poles flanking its front door, the work of local masters Charles Elliott and Doug Lafortune. Inside, the spacious foyer (also known as the Myfanwy Pavelic Gallery) features lovely display cases that hold two large stone carvings by Mohawk artist Michel Beauvais. And during this month you’ll see masks by Kevin Cranmer of Alert Bay, prints by Richard Hunt of Victoria and carvings by Chaz Elliott of Brentwood Bay. All this leads the way to the sixth annual invitational exhibition of First Nations, Inuit and Métis artists.

This show at first was a regular feature at the Tulista Centre, and has grown and evolved during the past two years at the Mary Winspear Centre. In fact, growth is a major theme. Many of the 40 artists who are participating in this year’s event are “entry level” talent and, while all of them share the spirituality that is an essential part of First Nations life, their range of materials and expressions is anything but traditional.

Further, the organization and administration has this year been taken over by the First People’s Cultural Council under the leadership of Debbie Hunt. It’s an opportunity for mentorship in arts programming.

While acknowledging that the show takes place on Coast Salish land, there is a clear intention to make it as widely inclusive as possible among the aboriginal cultures. Virgil Sampson is the mentor for the Coast Salish contingent; Tobias Tomlinson provides leadership for the First Nations from other groups — Mohawk, Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwa, Navajo, Chickasaw and Migmaw — who live here, while maintaining their tribal affiliation from elsewhere. Stephanie Papik represents the Inuit people, and Barb Hume the Métis.

The variety of their art techniques is unlimited. As I slowly made my way around the room, I discovered ceramics with feathers attached and designs engraved through the glaze, necklaces of silver and semi-precious stones, photography on canvas and a sea lion skull with flowers carved into it. Traditional designs on wooden panels, engraved copper bracelets and colourful screen prints strike a traditional note, but more in evidence were paintings by young urban artists. Their subjects reflect a contemporary reality rather than a memory of the past.

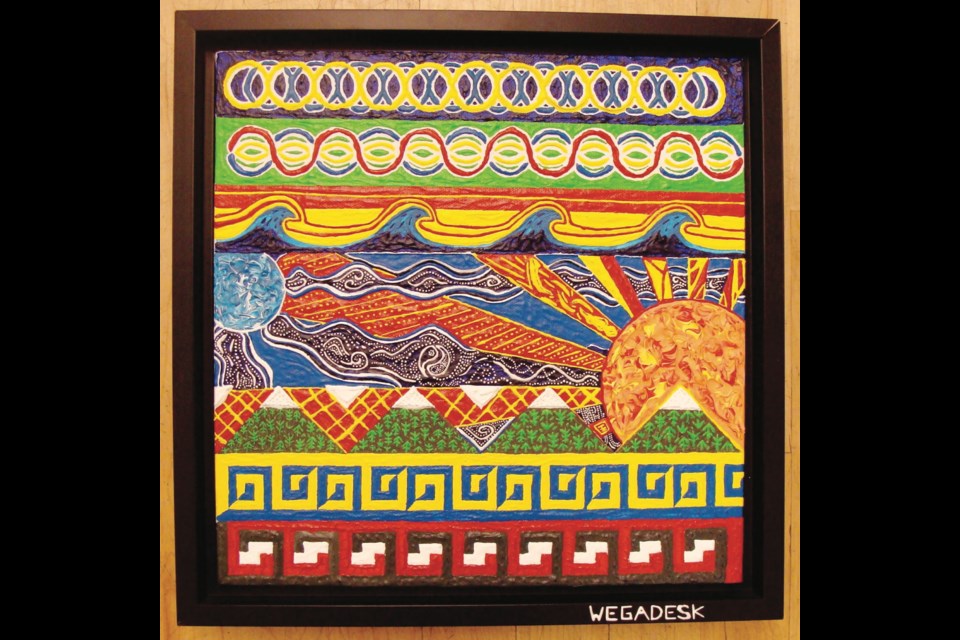

A particularly bright group of paintings by Wegadesk Gorup-Paul caught my eye. The artist was there at work, and laid down his brush and engaged me in conversation. Gorup-Paul is a young man from Nova Scotia who came here to train for the Canadian national diving team.

When his Olympic dreams didn’t pan out, he applied his considerable powers of concentration to the study of Sacred Geometry, as a way to help him overcome the disappointment. He’s articulate and gregarious, and, as he told me more and more about what’s behind his mandala-like creations, I realized that he’s quite a philosopher.

Gorup-Paul led me through the evolution of his large image of intersecting circles, and then we discussed his patient application of fields of dots.

“The dot,” he told me, is the “creating of a fact, a living truth.” Each is placed with loving care and represents the actions we, as humans, make during our life on Earth. “These actions are different from the Ultimate Truth,” he explained. Each of us has “these two beings within the human instrument.”

These paintings bear relationship to aboriginal paintings of Australia and Tibetan mandalas, more than any specific reference to his own native background. Of course, he noted, we are all “humans, children of God.” And it’s up to us to learn to live in harmony.

He said that all First Nations recognize a kinship, bringing them closer together than the rest of the Canadian citizenry. This exhibition is a demonstration of that tendency.

I continued my tour in the company of Brad Edgett, executive director of the Mary Winspear Centre, for whom this show is a personal project. Edgett worked for a number of years at the Arts of Man, a glamorous gallery of First Nations art in the Empress Hotel. The inspiration he found there stayed with him, and now he wants to “give back” and do his best for artists who have not yet achieved gallery representation.

In conversation, I learned some important things about the desire of the Winspear family to support native culture in the centre that they helped to found.

Frances and Claude Winspear were from Edmonton, where they established a performing arts centre. The family spent many happy summers at their property on Ardmore Road and, in 2007, their aunt Mary Winspear made a significant donation, which made it possible to replace the aging Sanscha Hall with the new centre named for her.

Her nephew Bill added another contribution toward this beautiful and useful facility. I was surprised to discover that it pays for itself mostly by rentals for art shows, memorial gatherings, weddings and theatre events. Edgett and I lamented the fact that government contributes only 30 per cent of its funding. It just doesn’t seem to get through to the people in power that the economic impact of any contribution they make to the arts is huge, and that cultural tourism is a major — and growing — industry on the Island.

But, as a friend of mine says: “Sing me no sad songs.” The current show is doing its part to help artists enhance their own “economic impact” and to develop entrepreneurial skills. In a number of ways, this show adds one more bright piece to the cultural mosaic of Sidney.

Sixth Annual First Nations, Inuit and Métis Art Show, Mary Winspear Centre, 2243 Beacon Ave., Sidney, marywinspear.ca, 250-656-0275, until Sept. 4. The show is open daily, with special events Thursday evenings. Admission is free.