PREVIEW

What: Life With Clay: Pottery and Sculptures by Jan and Helga Grove

Where: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

When: Continues through May 28

Admission: $13, $11, $2.50, free for those five and younger

Victoria was debating its sewage outfall problem as far back as half a century ago, says potter Jan Grove. And he’s got the sculpture to prove it.

In the mid-1960s he created a 148 centimetre-high work titled Quo Vadis — Latin for “where are you going?”. The sculpture, part of a new exhibit at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, looks like a totem pole constructed from industrial pipes.

“It’s a spoof on Victoria’s sewage problem. I made it in 1967. Every newspaper was writing about [the issue]. And we’re still having the same problem,” Grove said with a laugh.

Today marks the opening of Life with Clay: Pottery and Sculpture by Jan and Helga Grove at the gallery. Guest-curated by Allan Collier, it is the largest exhibition of work by these Victoria potters, showcasing 60 pottery pieces and 40 sculptures. The exhibit is representative of the Groves’ long career, which began in the 1950s and continued until their retirement in 2009.

The Quo Vadis piece typifies the Groves’ penchant for witty social commentary, says Collier, a collector of Canadian pottery. He ranks the German-born Groves as being among the best ceramists in this country.

“Their work is on its own, really,” Collier said. “I don’t have any trouble saying they’re in the top 10.”

This week Jan, 87, and Helga, who is 89, visited the gallery to help with the installation of their work. Taking a break, both waxed nostalgic about their arrival in Canada in 1965 from Turkey, where they’d taught ceramics. Urged to come to Canada by their friend, Victoria artist Herbert Siebner, Helga said she was persuaded partly by a crafty promise.

“I loved to ride horses. He lured me by saying: ‘You can ride there!’ ” she said.

Jan added: “Herbert didn’t tell us how cold the water was. Because were quite spoiled in Istanbul, swimming in the Black Sea. Still, five days after arriving, we bought a house on Sooke Road.”

That property, a former mink farm, had an outbuilding that they converted to a potter’s studio. It had to be scrubbed to remove the foul stench of fish — a staple of the minks’ diet.

It didn’t deter the Groves, an adventuresome young couple. Such obstacles paled in comparison to the hardship they’d seen Germany during the Second World War. Jan’s hometown was Lubeck, which was badly bombed. Helga, meanwhile, had fled Stettin (now the Polish city of Szczecin) with her mother during a Russian invasion, carrying amongst other possessions a hat-box containing a chicken.

At the gallery, Jan pointed out his 1989 work Three Ballerinas, a modernist sculpture portraying dancers who resemble spinning tops. It’s one of the most powerful works in the exhibit.

“I saw it as a challenge how to put those things together,” he said. “They are floating, because they are standing on the tiny points.”

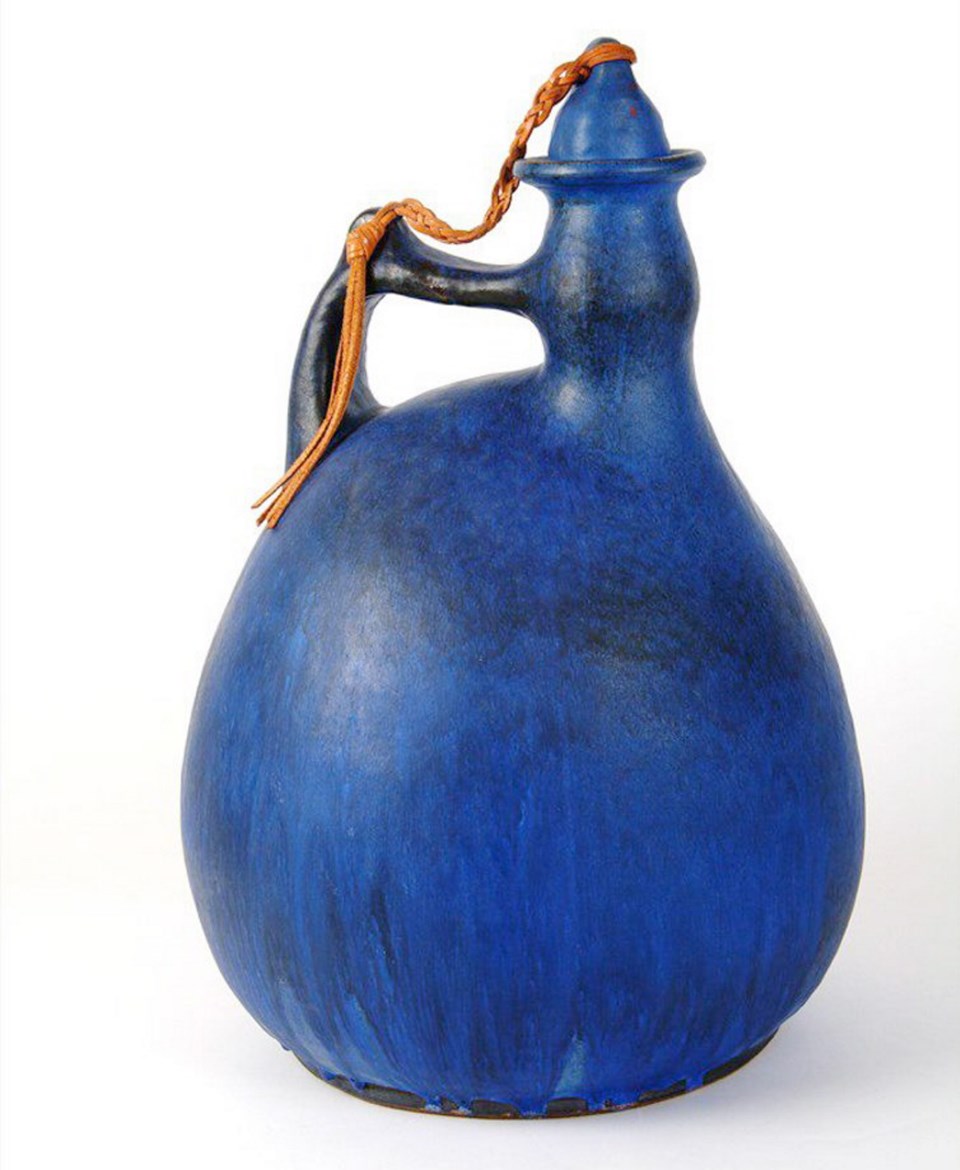

Such whimsical clay sculptures weren’t the Groves’ bread and butter. For years they supported themselves by making utilitarian earthenware objects: cups, bowls, vases, coffee pots.

While it’s never easy making a new start in a foreign country, the Groves had several things going for them. For one thing, their works reflected a refined Northern European esthetic. This was in stark contrast to most West Coast potters, who worked in a more rustic style influenced by Japanese ceramics and English potter Bernard Leach.

Another advantage was that the Groves had trained to a degree almost unknown in Canada. Their level of craft — clearly apparent in the show — is jaw-dropping. Both Jan and Helga had undergone years of rigorous instruction in Germany, where making pottery was a venerable craft controlled by guilds. Both participated in the journeyman system, with Jan achieving the formal designation as a “master” potter in 1956.

“Only then could I open my own studio in Germany. I was not allowed to do it before,” he said.

In an essay accompanying the exhibition, Collier writes: “When the Groves came to Canada in 1965, they discovered a pottery scene that was primitive in comparison to that in their native Germany … pottery [in Canada] was still seen as a mere hobby.”

Another thing helped the Groves get established in Canada. Siebner, whom they had first met in 1963 when he travelled to Turkey, was plugged into Victoria’s artistic scene. The Groves became acquainted with a group of his artist friends. Many (including the Groves, later on) became members of an influential artistic group, the Limners. The Limners included such notables as Walter Dexter, Pat Martin Bates, Colin Graham and Carole Sabiston.

As Collier notes, it was Siebner who assisted the Groves with getting their work accepted by a national exhibition in the mid-1960s. As well, Siebner put a word in with the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, where the couple had their first solo exhibition in 1966.

Ceramic art, even if created by the best potters, tends not to command the same price as paintings or sculptures. Nonetheless, amongst knowledgeable collectors, prices for the Groves’ work is on a steady rise, Collier said.

He recalls in years past finding some of their more everyday pottery in Victoria thrift shops. That’s becoming a rarity.

What attracted the Groves to pottery, a practice they maintained passionately for a lifetime? In part it’s artistic heritage, said Jan, whose mother was a master potter and father was a sculptor.

“Once you are stuck in the mud, you are stuck in the mud, you know,” he said, chuckling.

Jan added, more seriously: “I was never a painter. I saw things in three dimensions. That was perfect for pottery. I always saw everything as it should be.”