Before there was celebrity environmentalist David Suzuki, there was Ian McTaggart Cowan. Before science author Rachel Carson warned about pesticides, there was Cowan.

Before former U.S. president Al Gore made climate change a widespread public concern with the 2006 movie An Inconvenient Truth, there was Cowan.

Unlike Suzuki, CBC host of The Nature of Things, or even Carson, best-selling author of 1962’s Silent Spring, and politician turned movie-maker Gore, Cowan worked quietly. He had disagreements but made few enemies.

“Ian had an ego but it was not an in-your-face ego,” said Cowan’s friend and admirer Richard Hebda, curator of botany and earth history at the Royal B.C. Museum. “He was not one of those assertive activists in the public realm so much.

“He was an activist but within the system. He wrote to ministries and to ministers and had a strong influence there.”

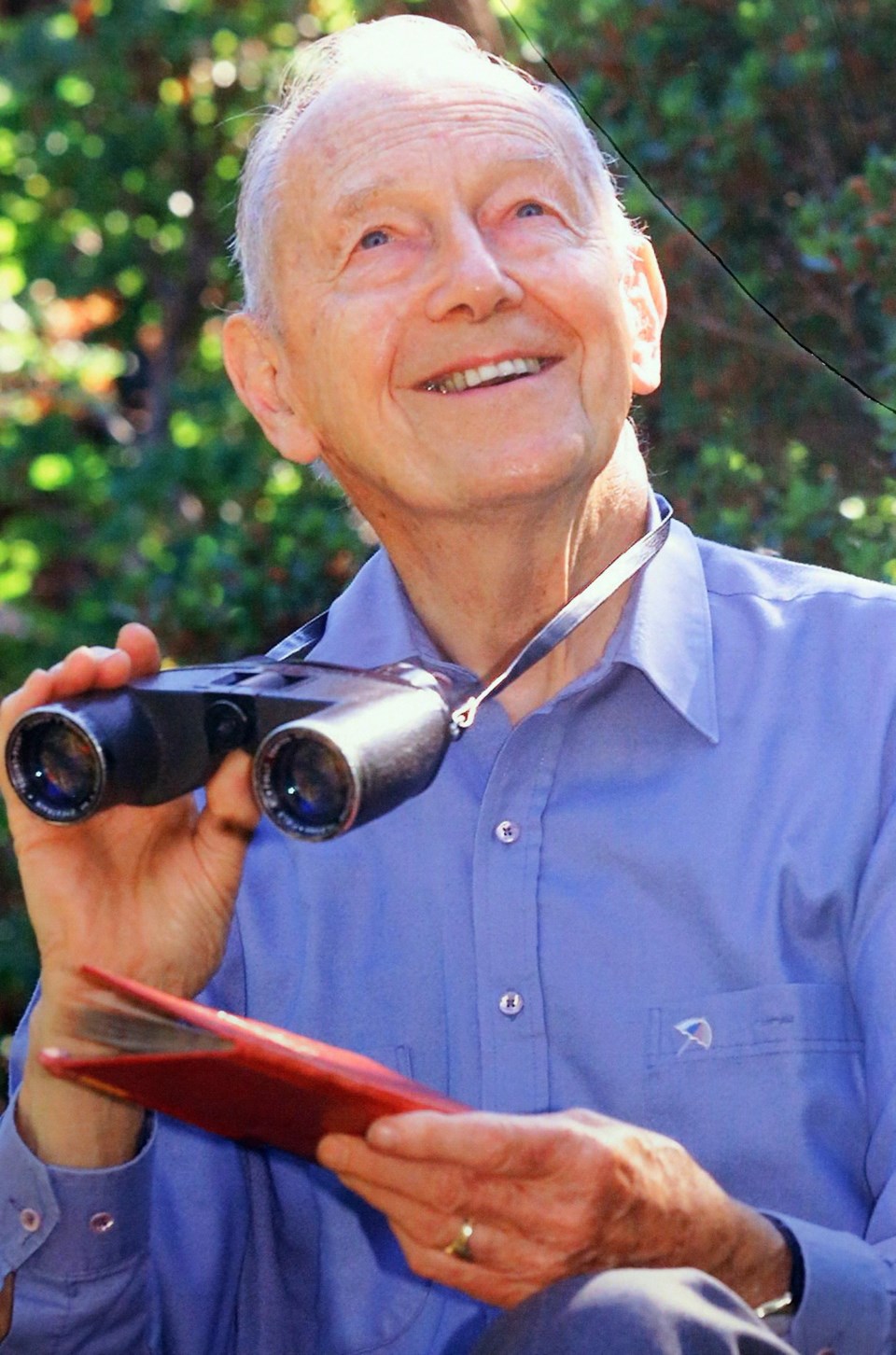

B.C. wildlife biologist, researcher and popular professor Ian McTaggart Cowan died of pneumonia on April 18, 2010, in Victoria, just two months short of his 100th birthday.

His wife, Joyce, died in 2002 and son Garry, a fisheries biologist, died in 1997. His daughter Ann Schau, a biologist who later became a university-trained musician, continues to live in Victoria with her geologist husband, Mikkel, in Cowan’s house.

Cowan’s life has now been chronicled in two books, both released this year: Ian McTaggart Cowan, the Legacy of a Pioneering Biologist, Educator and Conservationist, by biologists and Cowan colleagues Ronald K. Jakimchuk, Wayne Campbell and Dennis Demarchi, and the real thing by Briony Penn.

Cowan’s academic career began with graduate studies in vertebrate zoology, mostly deer, and continued with a 35-year stint as a professor of zoology at the University of British Columbia. His popularity among students remains a UBC legend. The Vancouver Fire Department once shut down a lecture because the hall was too crammed to meet safety regulations.

In 2005, the University of Victoria, where he was chancellor, honoured his name with the creation of the Dr. Ian McTaggart Cowan Professorship in Biodiversity Conservation. Two UVic scholarships have also been named in his honour.

He was a founding member of the National Research Council, chairman of the Environment Council of Canada and the public advisory board of the B.C. Habitat Conservation Trust Fund, and an author of the mammoth four-volume Birds of British Columbia. He was also inducted into the Orders of Canada and B.C.

But Cowan also leaves behind an enormous body of achievements and pioneering work.

While Suzuki didn’t begin his broadcast career until 1970, with a kids’ program called Suzuki on Science, and didn’t start The Nature of Things until 1979, Cowan was in television as early as 1955.

Continuing into the 1960s, he completed more than 100 programs in series now almost forgotten, Fur and Feathers, The Web of Life and The Living Sea.

In television-production circles around the world, he became famous by being the first to magnify and broadcast images of micro-organisms on TV in the 1960s.

Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, warning of the risk of chemical pesticides to creatures, most noticeably birds. But as early as 1947, Cowan was publishing papers on pesticides and their ingestion by mammals.

In 1952, he was writing and warning politicians about what was then called “climatic change.”

Author Penn, a journalist and environmental activist, said in an interview she will always regard Cowan as one of what she calls the “beautiful British Columbians.”

These are scientist/ observers who were and are enthusiastic about the natural history of B.C. But they are also advocates for its protection.

She sees him as one of the last great “field biologists,” scientists who went out into the wild and collected, even killed, specimens for preservation. They also spent many, many hours just observing.

Field scientists like Cowan were happy to listen to the knowledge, experiences and expertise of people such as native trappers and hunters to advance their knowledge.

“He had a huge regard for people who were willing to spend time observing,” said Penn.

“So native trappers, hunters, people who spent their lives in the bush, he really respected them.”

These field biologists have since been supplanted by scientists whose work is mostly done in the laboratory. Life science is now dominated by genetics and attempts to understand life on the molecular level.

But the work of people like Cowan has given us the modern field of ecology, examining how plants, animals and the earth interact and co-exist.

Penn said Cowan was no sentimentalist about nature or even the animals that fascinated him. When she arrived at his house in Saanich, a deer happened to stroll by and Cowan remarked “supper.”

He loved hunting, and regarded it as useful wildlife management, too. He probably had more in common with deer hunters than most urban environmentalists.

On the other hand, Cowan respected modern activists. In 1998, he wrote a letter to the Governor General supporting the induction into the Order of Canada of Paul Watson, an early Greenpeace member and founder of the anti-whaling Sea Shepherd Society. Watson was never so honoured.

Cowan was also always a teacher. When Penn first asked to interview him for her book, he agreed, but with a condition.

Any articles on his life had to be used for education or conservation. Otherwise, no interview would be granted.

“He told me: ‘I only want my life written about if it helps to promote and inform people about the incredible beauty of British Columbia,’” Penn said.

But for his daughter, Ann Schau, one of the most important legacies left by her father were his own notes, from the field, from conferences and discussions.

They were copious. But they were also neatly ordered and catalogued. They have since been donated to UVic, which has digitized them and made them available.

Schau noted her father would have been thrilled to hear students are already reading them and making use of them in their studies.

She said her father sought an order in all things, whether it was the preserved-specimen collections he helped systematize at the Royal B.C. Museum or his stamp collections that won him international awards.

For him, everything had a place and a connection that could be realized with a little observation and reflection. Schau said her dad always sought out the details that would allow him to understand and connect one thing with another.

“He saw details everywhere,” she said. “It was one of the things that always kept him going.

“Dad was always picking something up [and saying]: ‘Oh this looks interesting.’ ”