‘If there’s a book you want to read that hasn’t been written, then you must write it!” I first heard this adage while working on a mapping project in Peru. For me, the missing book was the exploration and cartographic history of the Amazon. So I began collecting early maps and travel accounts that would provide sources for when I would be able to devote time to writing.

In those years, my life involved a lot of international travel, and I took advantage of my peripatetic existence to seek out antiquarian bookshops and map dealers wherever I could. Fortunately, I had started collecting old maps before they became fashionable and prices skyrocketed.

Eventually I was able to devote a year to my Amazon history. By then I had come to the Vancouver area, and had at long last been able to unpack my collection, study it and prepare my magnum opus. That done, I went on to acquire a fat file of rejection letters from publishers.

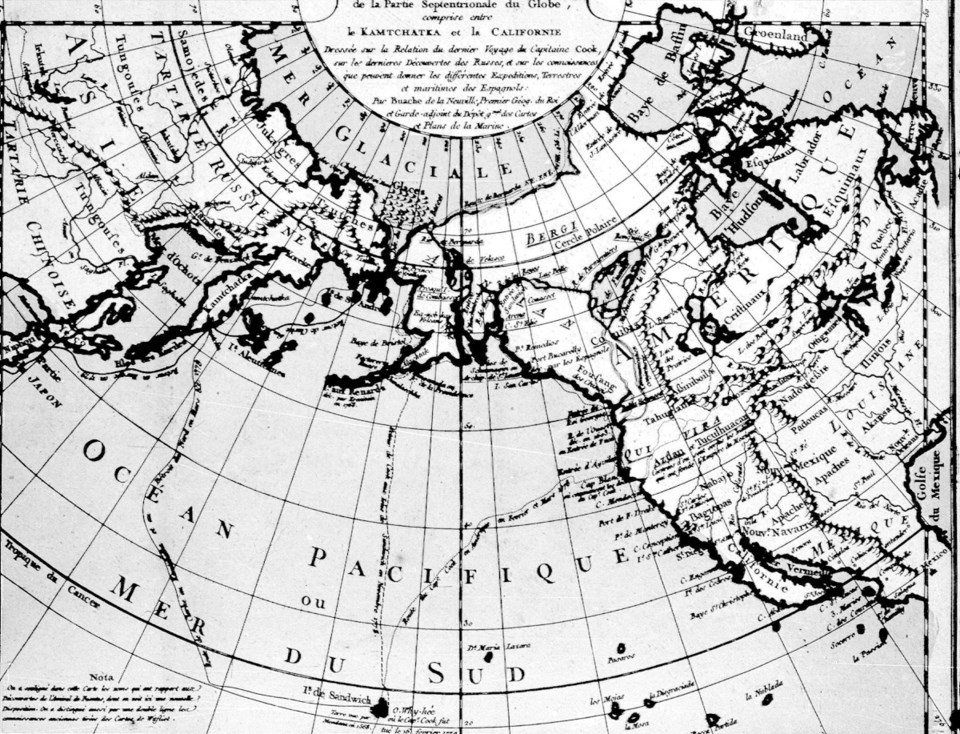

Changing tack, I mined my lode of Amazon research to publish several articles in specialist magazines. Fascinated by early cartography and the stories behind its progress, I helped compile a list of all the maps of B.C. that were made up to 1871, the close of the colonial era.

Fast-forward to 1991, when I planned a move to Victoria. A friend suggested that I might write the cartographic history of the island that was to be my new home.

It seemed do-able, and my decision was made easier by having already connected with a local publisher. A fellow map enthusiast, she had read one of my Amazon articles, and had invited me to send her a proposal should I ever feel like tackling a topic closer to home.

I imagined that researching and telling Vancouver Island’s story would be far simpler than relating that of the mighty river — it was a lot smaller for a start, and had a much shorter chronology. How naïve I proved to be! I prepared my proposal, and signed a contract with the publisher.

I was fortunate in my new home and in my timing. Before the advent of ABE and other specialist search engines of the Internet era, Fort Street supported Wells Books and several other antiquarian book dealers. In Sidney, Clive Tanner fostered a network of specialist bookshops as a tourism destination. Private libraries from all over the globe arrived as their assemblers came here to retire. The contents of many such collections eventually came onto Victoria’s receptive heirloom market.

As well as bookshops, Victoria was richly supplied with repositories of public and private documents. For my purposes, the most significant lay in the B.C. Archives, next to the distinguished Royal B.C. Museum. I found my first few visits there somewhat daunting. Not only did I not know what I should be looking for, I didn’t know how to go about the search.

Because I lacked the benefit of formal academic training in historical research, my initial studies were unstructured and uninformed. However, I soon learned that the archives staff possess not only a wealth of knowledge to draw on, but an attitude of courtesy and support towards researchers, no matter how inexperienced.

From my time as an army officer, I knew that “time spent in reconnaissance is seldom wasted,” so I began to acquire an overall understanding of the local history. I soon discovered the great breadth of the island’s written story, despite its relative brevity compared to the Chinese or even European sagas.

The local history reference room at the central branch of the Greater Victoria Public Library proved invaluable, and bibliographies in the books there helped expand my field of research. I built my own reference library of local exploration, within a budget, and noted where copies of scarcer books could be accessed. My earlier work listing all the known maps, including where copies were held, provided structure and substance for the cartographic aspect of the story.

I joined some of the many local historical societies, both for their lecture programs and for chances to meet others knowledgeable about or interested in aspects close to my own. In doing so, I discovered that Victoria is particularly well endowed with people — and media — concerned about local history and heritage. I felt among kindred spirits here.

Having done my prep work, and with a chapter plan in place, I again ventured into the B.C. Archives, now knowing what I needed to seek out. I delved into the wide variety of records held there: Not only the cartographic collection — primarily accessible by low-resolution microfiche — but also an extensive local history library, back numbers of regional newspapers on microfilm, a fascinating collection of photographs sorted by place, individual people and topic, a wealth of paintings and drawings, historic sound and film recordings, and official records and correspondence from all the varied forms of governance that this region has been blessed with.

Though bewildering at first encounter, the materials have been thoroughly documented, with card indexes and finding aids compiled over many years by devoted and skilled archivists.

Recently, the B.C. Archives has embraced the digital revolution with a will, and has begun to convert its vast holdings into a form compatible with research at a distance. Staff have implemented a high-tech reference system, in use by many similar institutions, called Access to Memory, familiarly known as “AtoM.”

Once complete, it will be an enormous advantage to researchers outside Victoria, and also to local researchers who may want to learn something outside of opening hours.

This supports the laudable access and outreach aims of the governing body of the now combined “Royal B.C. Museum and Archives.” There have been the inevitable grumpy murmurs as old hands experience some confusion and discomfort while becoming familiar with the new processes. But in time, they will find this change of great benefit.

Michael Layland is a former Royal Engineers mapmaker and the author of two books: The Land of Heart’s Delight, Early Maps and Charts of Vancouver Island, and the recently released A Perfect Eden, Encounters by Early Explorers of Vancouver Island.