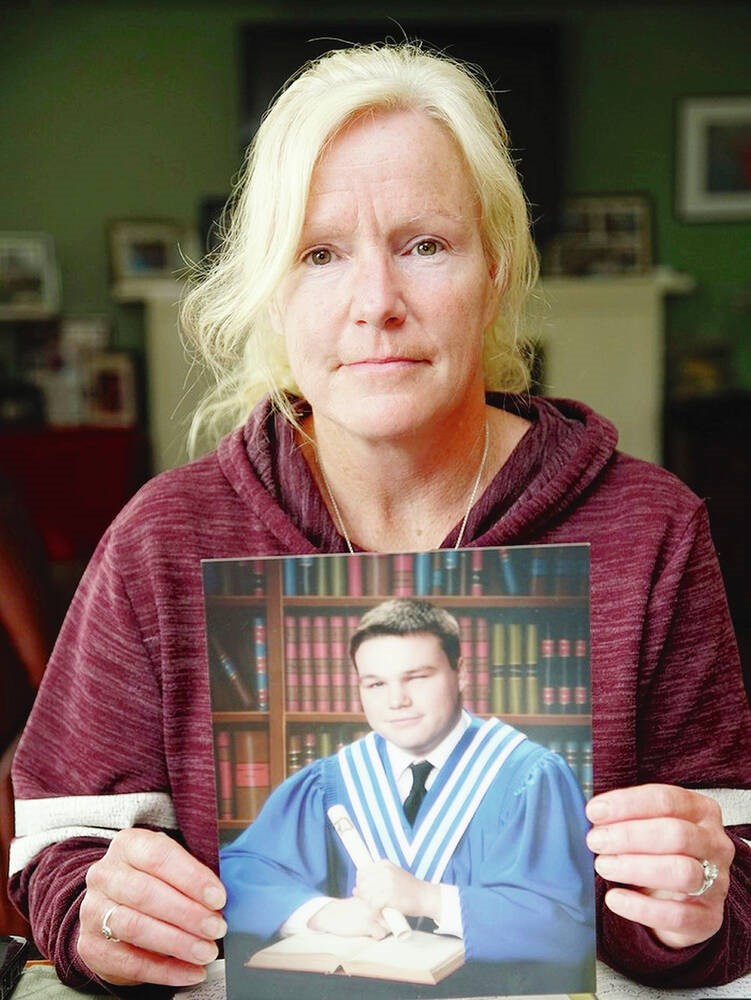

VANCOUVER — Nishelle Guignard’s son Braxton Leask, an outgoing soccer player who planned to become a pipe fitter, was murdered in his sleep a week before his 21st birthday. The mentally unstable gunman also killed Leask’s best friend, Dylan Buckle, in the same home outside Powell River.

It was early on the morning of June 17, 2017, that Guignard’s world shattered. And it has remained shattered ever since.

“I carry Braxton with me every day. The pain, it doesn’t go away,” said Guignard, a registered psychiatric nurse.

“It’s not just the date of the deaths or the date of his birth or the Christmases that you’re missing him. It’s every holiday, every time things come up, and now you’re figuring in hearings. So you don’t get a break. You’re trying to get better but, you know, I’m messed up. I still am.”

The hearings that Guignard attends are held by the B.C. Review Board, an independent tribunal that has legal jurisdiction over offenders that a court rules are unfit to stand trial or not criminally responsible for their crimes due to a mental disorder.

Jason Foulds, who was 19 when he shot Leask and Buckle, was found at his 2019 trial to have been experiencing delusional beliefs that night, and therefore was not held criminally responsible for his actions.

Despite the fact that Guignard works with mentally ill people as a psychiatric nurse, she disagrees with the court verdict, and argues the review board process is unfair to victims’ families and emotionally draining.

“There’s never been justice for the boys,” she said.

The conduct of the B.C. Review Board has been under intense scrutiny this month after it allowed violent offender Blair Evan Donnelly to leave Coquitlam’s Forensic Psychiatric Hospital on an unescorted day pass on Sunday, Sept. 10, despite its three-member expert panel finding he posed a “significant threat” to society.

Donnelly is accused of stabbing three innocent people at Vancouver’s Light Up Chinatown! festival, sparking outrage from many people, including Premier David Eby, who said he was “white hot angry.”

“The person’s history shows repeated acts of horrific violence. This should never have happened,” Eby said, announcing he’d appointed a retired police chief to investigate how Donnelly was released. “This investigation will also look at what’s needed to make sure something like this can never happen again.”

Donnelly, 64, killed his 16-year-old daughter Stephanie in Kitimat in November 2006 and was found not guilty of second-degree murder due to a mental disorder. He then stabbed a friend while on an unescorted day pass in 2009 and a fellow patient in 2017, both times without exhibiting any warning signs, said an April report by the review board, obtained by CHEK News reporter Rob Shaw.

What remains unclear is why Donnelly was granted an unescorted day pass this month. The three Chinatown victims suffered serious, but not life-threatening injuries, and he was charged with aggravated assault.

Many relatives and victims’ advocates agree with Eby’s take on this case. While acknowledging that mentally ill people deserve more support in B.C.’s overloaded health-care system, they also argue violent offenders should be separated from this group and treated in a more strict way.

“These are things that should not be happening,” said Rebecca Mayrhofer, whose brother Nathan was killed in Vernon in 2010.

Kenneth Barter used a hammer to murder his friend Nathan and then dismembered his body, but was found not criminally responsible due to a mental disorder.

Barter was rearrested while in the community unescorted, and charged with assault and assault with a weapon in 2022. Those charges were stayed this year and, as a result of the review board granting him an absolute discharge in 2019 for Nathan’s murder, he is no longer in custody.

Mayrhofer believes the “system is broken” and desperately needs a change.

There are supporters, though, who believe the review board does good work, in particular so mentally ill offenders can get medical help rather than being sent to prison, where there is less access to treatment.

They also argue these types of review boards have statistically good track records, in spite of high-profile cases like those of Donnelly and Barter.

Burnaby lawyer Paul McMurray has represented many clients with mental-health problems during his 44-year law career, including Foulds, who killed Leask and Buckle.

He said it’s hard to comment specifically on the Donnelly case because only the review board members know the information they had and whether they missed a red flag, but added the tribunal is typically quite stringent when it comes to releasing offenders into the community.

“In my experience, the review board is pretty careful and they’re pretty mindful of the concern to protect the public,” said McMurray, who has five clients now who are patients of the forensic psychiatric hospital after being found not criminally responsible for murder.

“The situation where you see somebody like Mr. Donnelly, who was found not criminally responsible of a very serious offence and then reoffends in a violent way, that isn’t common … because of the steps that patients have to go through at the forensic hospital to earn this sort of gradual release into the community.”

It is rare for offenders to be found not criminally responsible due to a mental disorder, with that verdict occurring in less than one per cent of adult criminal cases in the country, according to Statistics Canada. In B.C., that happened in 267 of 316,000 adult criminal cases between 2005 and 2012.

The Mental Health Commission of Canada funded an analysis of 1,800 people found not criminally responsible due to a mental disorder in B.C., Ontario and Quebec between 2000 and 2005. The National Trajectory Project found that after three years, 17 per cent of these people reoffended, which was half the recidivism rate of people released from prisons.

McMurray believes those recidivism rates are lower because offenders sent to prison don’t get the same extensive mental health treatment offered in psychiatric hospitals.

“Oftentimes people are released from jail having not had any sort of [mental health] treatment,” he said.

The review board is governed by the Criminal Code of Canada, according to B.C. mental health and substance use services, which provides medical treatment for people in custody and is an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority.

The review board had 256 offenders under its jurisdiction in the 2021-22 fiscal year, according to its most recent annual report, with roughly half in custody and the rest out of custody with conditions. Those numbers were down from 320 patients in 2016-2017, which is likely a result of the COVID-19 pandemic slowing down court operations, the report said.

These offenders are typically treated at the 190-bed Forensic Psychiatric Hospital in Coquitlam.

Every year they get an annual review of their case, which includes testimony from psychiatrists, and then the board makes one of three decisions: to keep the person in custody at the hospital for at least 12 more months; to give a conditional discharge, allowing them to live “where directed” outside the hospital with monitoring and treatment; or to give a full discharge, permitting them to live anywhere with no supervision or treatment required, and no longer being subject to annual hearings.

The B.C. Review Board has been directed by the Supreme Court of Canada to make “ ‘the least onerous and least restrictive’ disposition that is both protective of the public and meets the accused’s needs, including their need to be reintegrated into society,” board chair Brenda Edwards, a lawyer, said in an email.

The review board does not have statistics on how many people released on day passes reoffend while in the community, she said.

Postmedia asked repeatedly during the past week to interview a review board member, but the requests were refused.

The review board has about three dozen members, and each hearing is overseen by a panel of three. A typical panel includes a lawyer or judge, a psychiatrist, and a person with relevant experience, such as a social worker, police officer or nurse.

When making its decisions, the review board says, it considers the public’s safety, as well as the accused’s mental condition, reintegration into society, and other needs.

The hospital grounds have 41 transitional beds in nine cottages. Donnelly was placed in one of these for three days in 2022, even though a psychiatrist told the review board there were concerns because the unsupervised stays were not approved by the hospital or hospital staff.

When it comes to granting day passes for patients who are in custody at the hospital, like Donnelly, B.C. mental health and substance use services says that precautions are taken to protect the public and that early outings are accompanied by staff.

Over the years, though, B.C. families have raised concerns about this system.

Allan Schoenborn, who killed his three children, Kaitlynne, 10, Max, 8, and Cordon, 5, in Merritt in 2008, was up for consideration for supervised releases in 2015. His ex-wife Darcie Clarke, the mother of those children, was petrified by the suggestion, her cousin Stacy Galt told reporters covering the review board hearing.

Ila Watson of Chase said she was left speechless in 2019 when the man who killed her husband in 2016 was given an absolute discharge by the review board, after a court had found he was not criminally responsible for the death. “We have had to go through hell the past three years being hopeful justice would prevail,” she told the Kamloops This Week newspaper.

Brent Warren stabbed his seven-year-old son to death and injured his wife Linda in 2011, and two years later Linda’s father, Ben Bedarf, told a House of Commons committee that his family was worried about the uncertainty of when Warren would be deemed by psychiatrists to be able to return to the community.

“There should be a minimum sentence of 10 years spent in custody in a mental hospital or any institution deemed necessary for anyone who has committed murder and was found not guilty by reason of a mental disorder,” Bedarf said in 2013.

McMurray, though, defends escorted, and eventually unescorted, outings as a way to reintegrate people into the community, and said they are typically not granted until patients have progressed “pretty far” into their treatment.

“Obviously, it depends on some pretty serious scrutiny about what sort of risk the person poses,” he said. “If you’re found by the review board to be trustworthy in the sense of behaving yourself and not posing a risk.”

McMurray, who often argues before the review board that his clients should be granted passes, has sympathy for victims’ relatives and friends who have to attend these yearly hearings.

“To put myself in their shoes, would I find it an inconvenience and emotionally upsetting? Yeah, I probably would,” he said.

“But the flip side of it is that we don’t have a system where people are locked up and never released because we can never take a chance that they might reoffend no matter what they’ve done to try to address their problems. So the system we have tries to balance those things.”

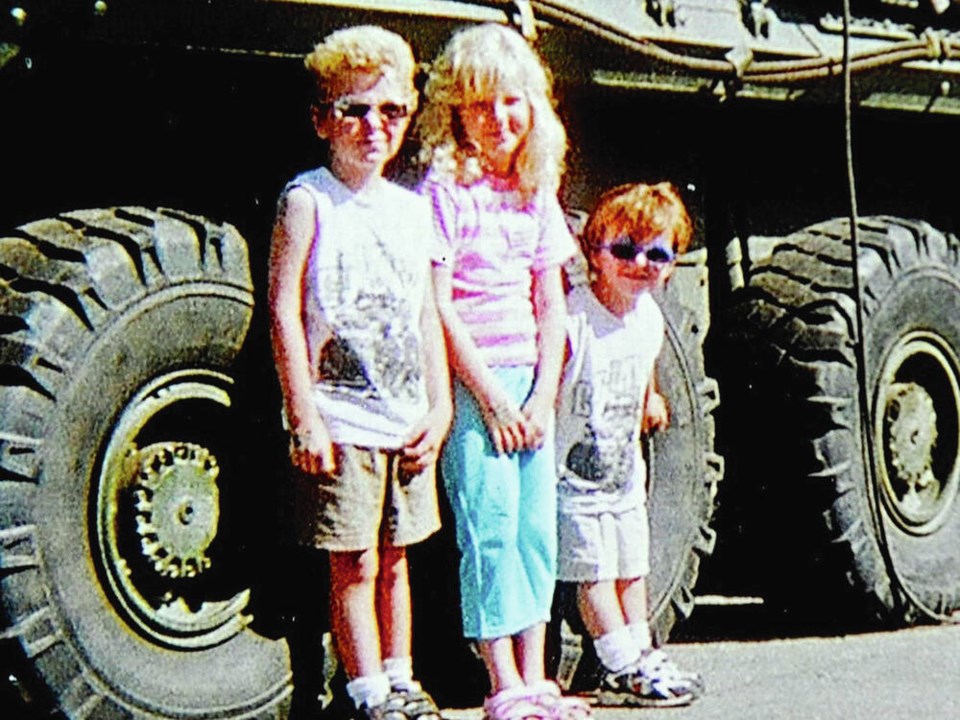

But Guignard doesn’t feel like there has been balance in her life since her son and his best friend were killed. Another friend, Zane Hernandez, was also shot by Foulds, but survived the attack.

The young men, who grew up in Powell River, were spending the summer working and living together in a house in Lund, on the northern end of the Sunshine Coast. They planned to pursue their career goals in the fall.

“Everyone loved them. They were just full of life,” Guignard said of the friends.

Foulds, then 19, was also from Powell River but his victims didn’t know him well, as he was two years younger. Early on the morning of June 17, 2017, Foulds entered their house while experiencing delusional thoughts and shot all three young men.

After Foulds’s murder trial concluded with the finding of not criminally responsible — a verdict that Guignard finds very upsetting — she and the mothers of the other two victims travelled from Powell River to Coquitlam to attend his first review board hearing in 2019.

Seeing her son’s killer in person was terrifying, but also frustrating because she couldn’t look him directly in the face. “You want to look at that person who murdered your son in his sleep,” she said. “It’s something I needed to do.”

The hearings were emotionally draining because, from Guignard’s perspective, they focused on making provisions for the offender, such as whether to approve unescorted releases to visit his out-of-town family. At the beginning there were two or three hearings a year, not just one, whenever there was a suggested change for Foulds, she said.

Guignard felt like victims’ families were afterthoughts in the process. For example, the hearings went virtual when the pandemic arrived in 2020, but while the lawyers and offenders had video links, she and other family members were connected by phone line only. After she spoke to a review board official, Guignard said, the families had video feeds for future hearings.

She also found out during a hearing in 2021 that Foulds had already been working in the community in a lumberyard, but no one had told the families, despite this being just a few years after the murders, she said.

“It makes me maddened. It makes me outraged. My son lost his whole life,” Guignard said, adding she also discovered during a hearing that Foulds was attending classes at a nearby college.

She believes the review board needs some form of victim services workers to help families better understand how the hearings work, so they are not left “in the dark.”

In the meantime, she is preparing for Foulds’s next review board hearing, and will write yet another victim impact statement.

“You’re just trying to get better and then these things creep up and then you’ve got to go through it again,” Guignard said.

“In one way, you don’t want to hear about it, or have another review board hearing. But if you don’t you have no idea what’s going on.”

Another change she’d like to see is making the eligibility for release much longer than it currently is.

“It shouldn’t be until five years after (the crime), at least, until they start saying, ‘OK, let’s integrate him into society,’” she said.

“It can turn your life upside down because they feel this person is ready to have an escorted pass or an unescorted pass. We get victimized constantly, constantly through the process.”

— With files from The Canadian Press