A group of Washington state legislators is calling on Premier John Horgan to better protect the headwaters of cross-border rivers from the threat of pollution from mining in B.C.

The 25 state senators and house representatives, led by Senator Jesse Salomon, sent a letter to Horgan last week urging the premier to “undertake needed reforms to improve British Columbia’s financial assurance system,” related to mine reclamation and cleanup.

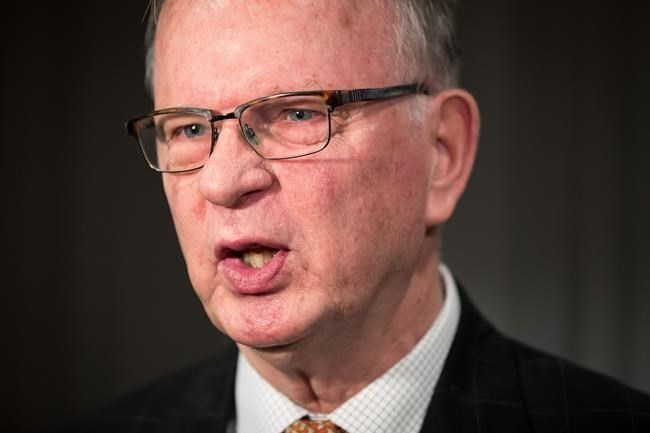

“We’re just concerned that there could be a tailings spill,” upstream of his state on critical salmon rivers such as the Skagit, Similkameen and Columbia, said Salomon, who represents Shoreline in suburban Seattle.

The state has spent “hundreds of millions of dollars to fix culverts, reconnect floodplains for salmon habitat,” is contemplating removal of a dam on the Similkameen, and “we can’t have mine tailings at the headwaters screwing all that up after the incredible work we’ve been doing,” Salomon said.

The letter backs concerns raised by environmental groups, such as Seattle-headquartered Conservation Northwest, which is campaigning against increased mining activity on the Canadian side of the border around rivers that flow south.

In particular, Conservation Northwest opposes a major expansion of the Copper Mountain mine near the Similkameen River and a mine exploration project near the headwaters of the Skagit River east of Hope.

Exploration rights for the Hope project, called the Giant Copper property, are owned by Imperial Metals, which also operates the Mount Polley mine north east of Williams Lake, which suffered the catastrophic failure of its tailings dam in 2014.

Conservation Northwest felt “a sense there was an opportunity for reform,” said Mitch Friedman, the organization’s executive director, referring the B.C. NDP government’s election commitments to make changes in mining regulation.

“It’s hard to drive the Crow’s Nest Highway and go by Princeton and not have the legacy of that mining history hit you in the face,” Friedman said about the open-pit Copper Mountain mine that stands out on the landscape and is considering an expansion that would involve raising the height of its tailings dam.

“I would really like to see the premier follow through on commitments that he’s made, in particular financial assurances (for mine cleanup bonds),” Friedman said.

Mines Minister Bruce Ralston was not available for an interview Friday, but in a background statement, ministry staff said B.C. has strengthened and modernized B.C.’s oversight of mining.

In August, 2020, the province amended the Mines Act to create a chief permitting officer, separate from the chief mines inspector, and established a mine investigation unit within the ministry that has already secured successful prosecutions, according to the statement by spokeswoman Meghan McRaie.

Selling B.C. as an environmentally responsible jurisdiction for mining investment has become a key strategy for Ralston as part of the province’s post-pandemic economic recovery plans.

B.C., however, faces pressure on several fronts with respect to pollution concerns around mining near cross-border river systems.

The Alaska conservation group Salmon Beyond Borders has also pushed B.C. to better protect rivers such as the Unuk, Taku and Stikine, which face impacts from mining and mineral exploration in the so-called Golden Triangle in the far northwest.

Those groups have lobbied U.S. lawmakers to invoke the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty in demanding stronger action on the Canadian side.

The letter signed by Salomon and 24 colleagues cites responsibilities that both sides are obliged to uphold that “prohibit pollution on one side of the boundary that would cause injury to life or property on the other side.”

“I’d be interested in seeing British Columbia’s response,” Salomon said. “Then we have to figure out what that means in terms of how we go forward.”