Nineteen stretches of critical salmon habitat on the Fraser River have less than a 50 per cent chance of thriving over the next 25 years, says a new study.

The good news: nearly a dozen solutions — from limiting pollution and controlling pathogens to tearing down barriers in the river and surrounding wetlands — could send the fish populations on a pathway to recovery.

The study, published today in the Journal of Applied Ecology, involved 12 researchers from two B.C. universities, the federal government, as well as First Nation, conservation and fisheries groups.

“Acting quickly is absolutely vital,” said Lia Chalifour, who led the study as part of her PhD work at the University of British Columbia and the University of Victoria.

“There are numerous case studies of species that were essentially studied to death because we needed more data or we needed more time.”

The Fraser River is the most important salmon-bearing waterway in Canada. But in recent decades, the number of salmon returning to spawn has plummeted.

Take sockeye salmon, the most iconic and commercially prized salmon in the province. Between 1980 and 2014, the Fraser averaged 9.6 million sockeye returns annually, with up to 28 million one year. But by 2020, salmon returning to the Fraser River fell to an all-time record low of 293,000.

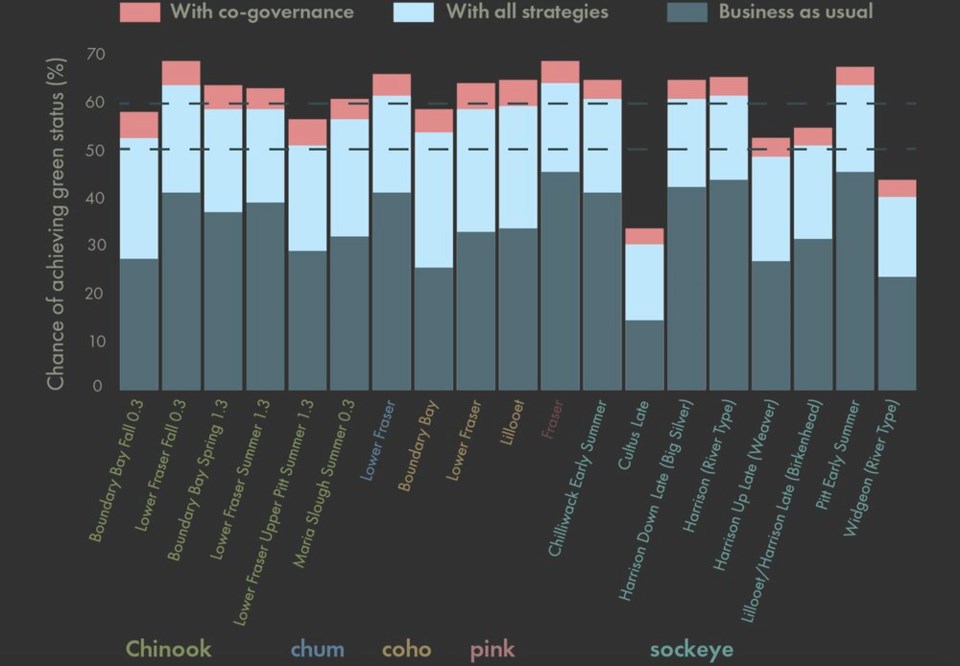

More widely, those kinds of returns have meant 19 out of the river’s 54 wild Pacific salmon conservation units — ecologically and genetically distinct groupings of salmon — are on the decline, found the researchers.

Much of the damage to salmon populations comes from shrinking access to freshwater habitat — whether in upriver spawning grounds or the brackish waters used to acclimate to the ocean.

A study released last summer by the University of British Columbia and Raincoast biologists found 85 per cent of the Lower Fraser’s salmon habitat has been lost since the 1850s. From Hope to Delta, a network of culverts, dams, dikes and flood gates prevent salmon migration.

The researchers recommended 1,200 barriers be torn down to undo the worst impacts of city building and agricultural development.

Earlier this year, a hole punched showed the rejuvenating power of a single breach. Within weeks of punching a 30-metre hole in a jetty at the mouth of the Fraser River, scientists observed thousands of young fish swimming toward habitat blocked for over 100 years.

To figure out what resources will be needed to rehabilitate salmon populations on the Fraser River, Chalifour and her colleagues brought together 104 experts from First Nations, federal and provincial governments, recreational and commercial fisheries, universities and NGOs.

Their goal: figure out the most cost-effective way to pull back Lower Fraser River salmon from a dark future.

Through a process of structured decision-making, the researchers spent days identifying the problems facing all 19 wild salmon populations. Then the experts independently assessed each conservation strategy and the likelihood they would succeed.

The threshold for success was set at achieving “green status” under Canada’s Wild Salmon Policy — at that level, the fish would be able to sustain a fisheries industry while still supporting all the ecosystems that rely on them.

That meant looking at a collection of watersheds covering over 230,000 square kilometres, much of it in some of the most heavily urbanized areas of the province.

“It's a very intense process,” said Chalifour. “We essentially wrung their brains of information.”

After crunching the numbers, Chalifour and her colleagues ran all the answers through an algorithm to assess each strategy based on its likelihood of success, how much it would cost and the benefits it would provide.

Developed by UBC researcher Tara Martin, the whole-of-society process has helped back conservation strategies in places as far removed as the Lake Eyre Basin — a swath of land covering a sixth of the Australian continent — and the Saint John River in New Brunswick.

When the calculations were finished, the researchers found that over the course of the next 25 years, giving the wild salmon populations a decent chance to thrive would cost between $45 and $110 million every year.

At the high end, a raft of conservation measures would give all 19 conservation areas on the river better than a 50 per cent chance of thriving, with seven having a better than 60 per cent chance.

But even a $20-million yearly investment would boost 14 of the 19 salmon populations above the 50 per cent threshold — a cost equivalent to $4.25 per B.C. resident.

Add to that a new model in co-governance between First Nations, the federal and provincial governments, and another five conservation areas climbed above a 60 per cent chance of thriving.

Chalifour said the $647 million the federal government promised last year to restore Pacific salmon could cover “some good chunks” of what’s needed. But even at the low end, it would fall far short of bringing wild salmon populations back to sustainable levels across the province.

Chalifour says the federal Pacific salmon strategy means that money is spread out over a broad mandate that sometimes includes species that aren’t even salmon.

More importantly, says the researcher, there’s no framework set up to prioritize where the money goes in a strategic way. In other words, there’s no scientific or community-level accountability for how that money is spent.

“We do need to know what those costs are,” she said. “…otherwise we're just throwing money, somewhat blind, and not knowing whether we're getting the biggest bang for our buck.”

No amount of money can abate all the pressures facing wild Pacific salmon.

At sea, salmon are threatened by everything from climate change-driven ocean heat waves to overfishing and potential drops in food resources.

“Water is still going to warm up to some degree,” said Chalifour.

Some worry climate change could shift the nature of prey relationships with sea lions. Others say warmer waters could push returning salmon to make landfall further north in Alaska, where they could get scooped up by fishing boats before returning to B.C. waters.

“There are limitations, for sure,” said Chalifour.

On the other hand, not all the money required to help safeguard wild salmon will disappear into the landscape or underwater.

Tearing down barriers and restoring wetlands will require people, and Chalifour says any significant investment would help provide jobs in green infrastructure, restoration and seismic works.

But rolling out any future management strategy first requires understanding the state of salmon today, and Chalifour says current federal management strategies are failing in two glaring ways.

First, due to a lack of monitoring, B.C. fisheries lost their sustainable status over the last few years. In their report, the researchers point to Canada’s fisheries management bodies and their conflicting roles in managing the recovery of salmon all while supporting commercial fishing interests.

“This conflict has contributed to the slow reaction of management bodies to address these pressures,” write the researchers.

And second, building out a co-governance model with First Nations to manage wild salmon, clearly net massive gains for salmon and people.

“This framework can easily be adapted to any study region,” Chalifour said. “We can just get more and more efficient.”