Steven de Jaray filed a civil lawsuit against the Attorney General of Canada, claiming he lost millions in personal wealth after he was charged in 2010 with trying to export electronics that government officials said could be used in military weapons. De Jaray said the charges laid by the Canada Border Services Agency contributed to the collapse of his company and other business interests, before they were withdrawn in 2011.

The government reached an out-of-court settlement with de Jaray in 2013, he said. But he is prohibited from revealing the amount paid to him from Ottawa’s taxpayer-funded coffers.

However, CTV’s W5, in an investigative segment that airs Saturday, reports that de Jaray received the second-highest government settlement in Canadian history, estimated to be around $10 million.

Ottawa paid Syrian torture victim Maher Arar $11.5 million in 2007. David Milgaard, wrongly accused of murder, received $10 million from Saskatchewan in 1999. If the payment in this case is on that scale, why so high?

De Jaray’s lawyer, Howard Mickelson, won’t confirm the amount. But he described his client as a former successful businessman who cannot rebound professionally with the albatross of this case around his neck.

“I can’t discuss the settlement, but I don’t think there is any question that the economics of this on him was in the millions of dollars. The conduct of the government in this case happened to economically destroy someone who was a proven success,” Mickelson said.

He and de Jaray believe there was a larger issue at play in this story, although Mickelson acknowledges the theory has not been tested in court because the case was settled and did not go to trial.

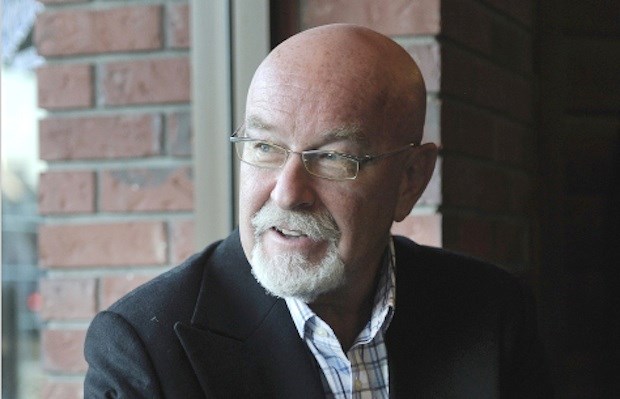

In an interview, de Jaray alleged that his company, Apex-Micro Electronics in Delta, was not accidentally accused by zealous Canada Border Services officers in 2008. Rather, he alleged, it was targeted to appease U.S. demands that Ottawa prove it could be tough on exporters of terrorism-related goods, at a time that Canada’s border was being called sieve-like.

“How did (the government) get it so wrong? They got it so wrong, the theory of the case being, that there was a need to prosecute somebody in Canada for some violation of this (Export) Control Act,” Mickelson said. “My client became that somebody.”

De Jaray is a victim with a blemished past, perhaps not unlike Milgaard who some say was wrongly pursued by police because of his troubled youth.

In 2004, de Jaray admitted to insider-trading reporting violations and to failing to install adequate compensation controls at a former company. was slapped with a $100,000 B.C. Securities Commission fine and a nine-year securities ban.

But he insists his more recent business Apex, which manufactured microchips and other electronics, was a very successful venture that was ultimately ravaged by an unfair federal government investigation.

He points to information posted on the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks. It reported on a May 2008 meeting in Ottawa in which U.S. officials said they would consider Canada’s request for the lifting of certain trade sanctions if Canada pursued prosecutions and jail time for exporters who posed potential security threats.

De Jaray believes he was caught in those political negotiations. Canada Border Services would not comment for this story, citing the Privacy Act.

The taxpayer-funded awards given to victims Arar and Milgaard were announced to the media and came with public apologies; whatever de Jaray received was settled out of court by the two parties, who say they are bound by an agreement not to reveal the monetary details.

===

CLICK HERE TO VIEW MORE PHOTOS, or tap and swipe the image on your mobile device.

===

Steven Allan Wylie de Jaray describes his former life, in court documents, as a high-rolling entrepreneur who founded at least seven companies between 1978 and 2002.

He lived in a West Vancouver mansion overlooking the Eagle Harbour Yacht Club — one of three local yacht clubs to which he held memberships. He mingled in elite social and business circles. He and his late wife, according to his civil suit, joined other parents in founding the prestigious private Collingwood school, and expanding Mulgrave prep-school, both in West Vancouver.

He built one of his companies, Aim Global Technologies of Delta, into a multi-million operation, listed on the Toronto and American stock exchanges. In 2000, it was named by Deloitte and Touche one of the fastest-growing technology companies in North America.

But in 2004 he entered into a settlement with the B.C. Securities Commission, admitting to improperly reporting insider trades; needing tighter salary rules after the board raised concerns he was overpaid by $400,000; and failing to disclose that he was given a Ferrari by a consultant who worked for the company.

Today, de Jaray admits he made mistakes at his former company, although he insists they were unintentional ones not meant to harm the company or its shareholders.

“I made a mistake on the filings. I was happy to accept that and I paid the fine,” he said.

In 2002, de Jaray founded Apex, which he estimated grew to more than 200 employees and $40 million annually in sales by 2008.

He also started a winery in Oregon, promising it would quickly become one of the state’s largest and most popular labels. Newspaper stories about the venture featured de Jaray sipping vino by rows of barrels.

That flamboyant life began to unravel days before Christmas in 2008, when Apex shipped two boxes of electronics — including microchips that could be used in products such as flatscreen TVs and video game consoles — to Hong Kong. This was routine for the company, which made or sourced components for major electronics manufacturers in the aerospace, telecommunications, medical and automotive industries.

The boxes, labelled “printed circuit board assembly,” were flagged as suspicious at the Vancouver airport.

A CBSA officer who thought the contents could violate export laws contacted the Department of Foreign Affairs. Based on specification sheets found on the Internet, Foreign Affairs deemed the parts could be used in weapons — and therefore were not allowed to be exported without permits.

De Jaray said he consistently told federal officials that the components were not in violation of export laws and could not be used for military purposes. His lawsuit alleges government officials never called the manufacturer of the components to check if the specifications were being interpreted accurately.

“The notion you could use these for anything remotely strategic is ridiculous. These were common, available every day, old technology,” he said in the recent interview.

CBSA officers raided de Jaray’s Delta offices and West Vancouver house in February 2009. He says that ruined his reputation in social and business circles, contributed to the collapse of Apex and the Oregon winery, and alienated family and friends. He moved abroad, he said, because the investigation destroyed his financial interests and personal relationships.

“The impact on my life was horrific,” he said.

More than a year went by before the CBSA issued a press release in May 2010 saying it had charged de Jaray and his daughter, then 26 and working with him at Apex, with exporting goods without a permit under the Export and Import Permits Act, and failing to report the exporting of goods under the Customs Act.

The press release alleged the electronic chips in the boxes were dual-use goods — they could be used commercially or for “a significant military application” — and were restricted under Canada’s Export Control List.

The director of CBSA’s criminal investigations division is quoted in the release, saying “Canada has a responsibility to ensure that goods entering the international market from Canada do not pose a threat to international peace and security.”

De Jaray’s civil suit says the press release “branded (him) as the equivalent of a terrorist or weapons dealer.”

His wife died of cancer in December 2010, not knowing the outcome of her daughter’s legal nightmare.

De Jaray alleges in his lawsuit that he hired a former deputy director of Foreign Affairs’ export control division, Tom Jones, who had worked with the Export Control List and runs a consulting business, Canadian Export Consulting Services, in Ontario. His company’s 2011 review determined Apex’s microchips were not designed for miliary use and not prohibited from export.

The government had said the microchips were military grade mainly because of the temperature range in which they could operate, essentially from arctic to desert environments.

De Jaray claimed the consultant’s report said the proper interpretation of the manufacturer’s specification sheets was that the microchips had survived stress tests at high and low temperatures — but could not operate in those extremes without suffering degradation.

The lawsuit quotes from the report: “It is our opinion that the (components) are not enumerated in the ECL (Export Control List) and consequently not controlled.”

Four months after de Jaray’s lawyers provided this report to federal lawyers, the charges against de Jaray and his daughter were stayed, in August 2011.

Mickelson said no explanation was given for the stay, but noted Jones and his colleague are the top experts in the country on the Export Control List.

De Jaray, Mickelson said, has not received a public apology from the federal government.

“It would be nice to have a very public vindication, but unfortunately that can be one of the sacrifices that have to be made in order to reach a compromise.”

In Oct. 2012, in response to the civil suit, the federal government maintained it had its own expert report indicating the components were problematic, and would only say the decision to drop the charges was “a matter of prosecutorial discretion.”

It disagreed that de Jaray deserved any payment from Ottawa.

But the government appears to have changed its tune at some point in 2013, when it settled out of court with de Jaray.

“It was such a head-scratcher,” Mickelson said. “And you wonder how did this happen? It just so happened WikiLeaks gave us the (alleged) explanation.”

American documents posted on WikiLeaks chronicle a May 2008 meeting in Ottawa, attended by Frank Ruggiero, deputy assistant secretary in the U.S.’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, to discuss Canada’s export controls. The cable said Canada expressed confidence it had addressed U.S. concerns about inadequate screenings of goods leaving the country, and asked for American restrictions to be eased to allow an easier flow of certain goods across the border.

Ruggiero said, according to WikiLeaks, this could be considered if Canada achieved “substantial progress on two current law enforcement issues” in which U.S. officers alleged they were “not getting Canadian co-operation.”

Also at the meeting were two American Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers, who asked Ruggiero to press Canadians for better co-operation on export files.

“The ICE officers argued that until the price to be paid for export control violations is the same in Canada as it is in the U.S. — prison — adversaries will persist in abusing Canada as a venue from which they can illegally procure and export U.S. defence technologies,” the WikiLeaks report says.

De Jaray alleged in his lawsuit that Canada’s negligence led to the wrongful criminal charges.

“We were completely innocent people who CBSA conspicuously used in trade to the USA,” de Jaray said.

With the facts never tried in court and the federal government refusing to discuss the file, it may be impossible to ever know who did what and why in this case.

And exactly how much money taxpayers financed in the court settlement.