A study of sea lice on wild and farmed salmon by Canadian scientists found a “positive trend” of sea lice on wild salmon in the areas studied, but “no statistically significant” association that could be attributed to fish farms.

The Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat response is based on a national peer review process, with contributions by a dozen Fisheries and Oceans Canada scientists, two CSAS scientists and a data scientist from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.

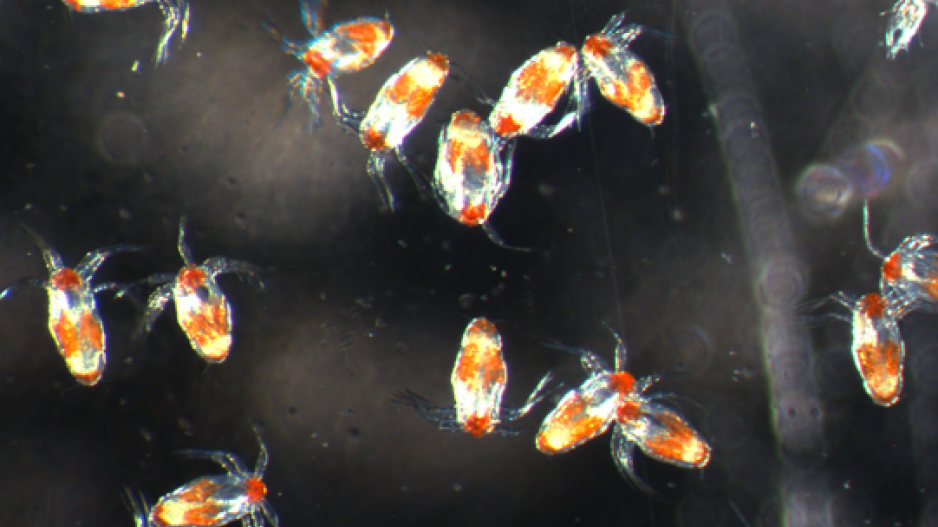

“Our analyses provided quantitative estimates of the association between the weekly number of farm-origin L. salmonis copepodids (salmon louse) in the marine environment in British Columbia and their contribution to infestations on wild juvenile Pacific salmon under current farm management thresholds,” the report states in its discussion summary.

“We saw a positive but statistically insignificant association in all four regions studied.”

The report states it is “accepted” that fish farms are “potential reservoirs” of sea lice.

“What is still debated is the effect of sea lice infestations on wild salmon populations, and the importance of the contribution of L. salmonis originating from farms to the overall sea lice burdens observed on wild salmon.”

The report acknowledges previous studies that found correlations between sea lice infestations in salmon farms in B.C. and wild salmon, including a 2018 study by Omid Nekouei et al.

That report used sea lice count and management data from farmed and wild salmon over 10 years (2007–2016) in the Muchalat Inlet area. It concluded: “Our analyses indicated a significant positive association between the sea lice abundance on farms and the likelihood that wild fish would be infested. However, increased abundance of lice on farms was not significantly associated with the levels of infestation observed on the wild salmon.”

The CSAS report notes that data for Muchalat Inlet was not available for the latest study, which is based on surveys in six coastal regions: Broughton Archipelago, Discovery Islands, Port Hardy, Central Coast, Clayoquot Sound and Quatsino Sound.

The report notes that other studies (Morton et al., 2004; Krkosek et al., 2005; Price et al., 2011) were based on sea lice counts on wild salmon before and after migrating past salmon farms, and used modeling and-or statistical analysis to draw associations between sea lice in farmed and wild salmon.

“With or without farm sea lice infestation or environmental data, these studies identified increases in sea lice … infestation on wild salmon after migration past one or more salmon farms which they attributed to the farm(s).”

The research used for the latest CSAS response had greater access to sea lice data from salmon farms.

“In the present study, availability of farm-level data provided an opportunity to better estimate the association between sea lice on salmon farms and sea lice infestations on wild Pacific Salmon,” the CSAS response states.

It notes that a number of natural environmental conditions can result in increased sea lice infestations in wild salmon, including salinity and water temperature.

“Across all years, the mean prevalence of L. salmonis infestation was highest on wild juvenile chum salmon in Clayoquot Sound and lowest on chum and pink salmon in Discovery Islands.

“No statistically significant association was observed between infestation pressure attributable to Atlantic salmon farms and the probability of L. salmonis infestations on wild juvenile chum and pink salmon in Clayoquot Sound, Quatsino Sound, Discovery Islands, and Broughton Archipelago,” the report concludes. “However, the data suggests a positive trend in all studied areas.

“The lack of statistical significance implies that the occurrence of L. salmonis infestation on wild migrating juvenile Pacific salmon cannot be explained solely by infestation pressure from farm-sourced copepodids.”

The First Nation Wild Salmon Alliance (FNWSA), which has lobbied for the removal of all open-net salmon farms from B.C. waters, is criticizing the CSAS report.

“How could this internal DFO reach a conclusion that conflicts with decades of peer-reviewed research?” the FNWSA asks in a news release.

The FNWSA says DFO scientists “relied exclusively on salmon farm industry data,” and questions why data from fish farms in Muchalat Inlet was not available for the latest study.

“This is the only region in the world where data was taken prior to arrival of the farms,” the FNWSA notes.

The FNWSA also alleges that the salmon farming industry “under-reports their lice by up to 50 per cent at times when their count is audited by DFO — which is why industry data on sea lice on wild salmon never aligns with research from Canada’s universities and research stations.”

The B.C. Salmon Farmers Association says the CSAS report is just the latest to conclude that open-net salmon farms have minimal impact on wild salmon in terms of transmitting disease.

“This comprehensive CSAS report adds to the nine previous CSAS science reviews (2020) on salmon aquaculture in B.C. that concluded ‘minimal risk’ to Fraser River Sockeye salmon from all relevant fish pathogens of concern,” the association said in a statement.

“The current report indicates that there is no statistical correlation between sea lice counts on wild and farmed populations of salmon — meaning that the presence of farmed salmon does not appear to have a measurable impact of sea lice counts on wild salmon populations.”