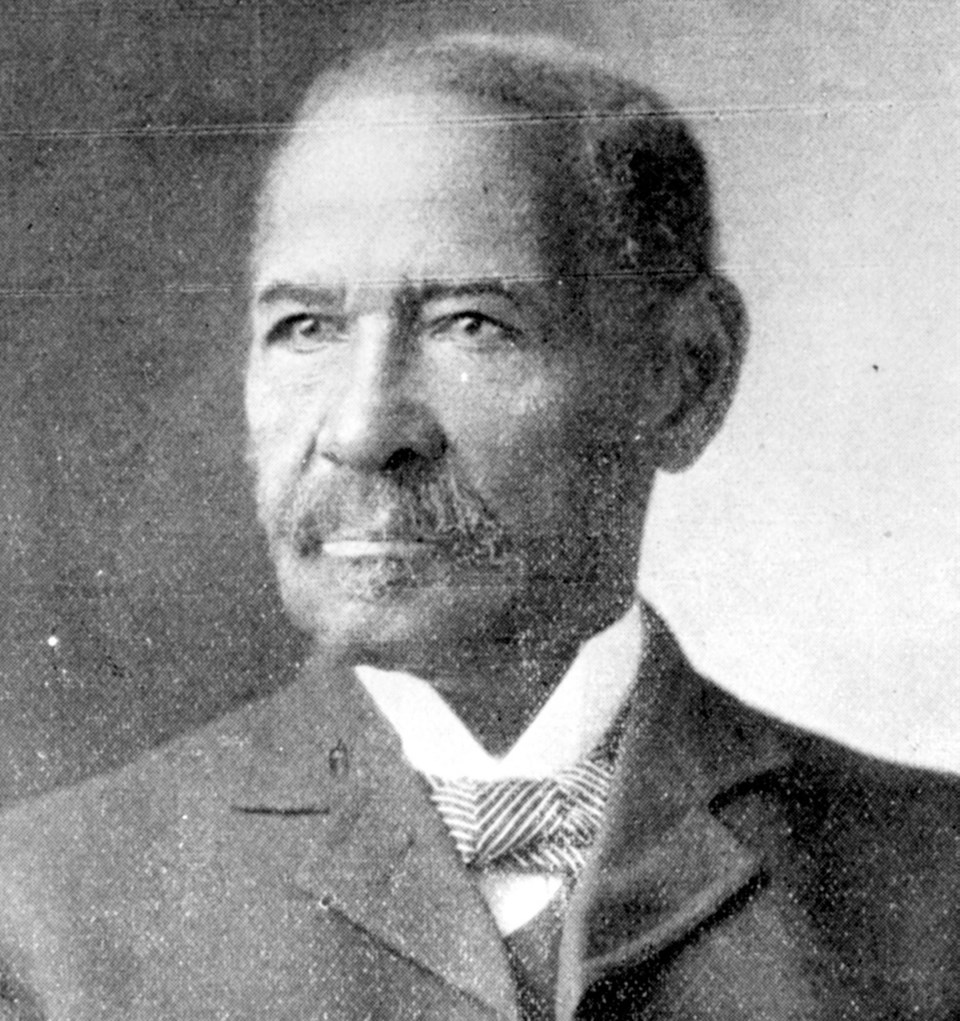

The City of Victoria has declared today to be Mifflin Wistar Gibbs Day, in honour of Gibbs becoming the first black elected official in Canada on Nov. 19, 1866, 150 years ago.

Gibbs served on city council for three years before returning to the United States.

Today is also Douglas Day, in honour of Sir James Douglas, and marks the anniversary of Douglas proclaiming British Columbia to be a Crown colony in 1858.

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs and Nathan Pointer were probably not looking for trouble when they took their wives to a benefit concert in Victoria’s theatre on Wednesday evening, Sept. 25, 1861.

Trouble found them, though, because of their skin colour. They were the first blacks to take seats in the theatre, and that caused problems.

Emil Sutro was one of the first to object. He had been scheduled to play in the orchestra, but refused to take the stage unless the “coloured people” were moved out of prominent seats in the dress circle.

The performance went on without Sutro, but as it neared its end, someone threw a package of flour on Gibbs and Pointer. Gibbs responded by punching a man named William Ryckman.

As the British Colonist reported the following day, a general row started, with several persons knocked down and trampled. The fire bells rang and the police were called to put an end to the disturbance.

“No one can defend the particular act by which several of our coloured citizens were gratuitously insulted,” the Colonist said in an editorial. “They bought and paid for their tickets for the concert; took the seats the tickets called for; and consequently the right they thus acquired ought in all cases to be maintained.”

The newspaper’s position was clear.

“It matters not whether a man carried a black skin or a white one under his shirt,” said the editorial, which was probably written by Amor De Cosmos, the newspaper’s owner at the time. “If he has lawfully purchased a privilege to attend a concert no one should interfere with his enjoyment.”

The editorial provides a window into 19th-century attitudes about race in Victoria. It said many people in the community believed in the “superiority of the Caucasian over the African,” and added that the majority of people in the community would not want to attend concerts if it meant they would be in close contact with blacks.

Further riots were possible, it said, with a risk of loss of life. “That our coloured population will ever succeed in being admitted into our theatres to mix promiscuously with the whites we do not believe,” the Colonist said.

“Coloured amusement-seekers will either be excluded or will have to be content with a place by themselves.”

The theatre ruckus dominated the headlines for several days. The Colonist ran a letter from someone identified only as “an offended Englishwoman,” noting that Sutro, a Jew, was himself part of a much-persecuted race, and as such his sympathies should have been with the blacks.

Another letter, from “an Englishman,” said that the concert had been a swindle because the organizer had not warned patrons that blacks would be admitted.

On Sept. 30, the matter went to court. Gibbs and Pointer accused Ryckman of flouring them, while Ryckman countered with charges of assault against Gibbs and Pointer.

Gibbs pleaded guilty, and the charge against Pointer was dismissed for lack of evidence. A few days later, after several witnesses testified that Ryckman could not have thrown the flour, the charges against him were dropped.

Gibbs was fined five pounds and ordered to pay for a new coat for Ryckman. Two other men, J.A. McCrea and Edward F. Boyce, were charged with conspiring to cause a riot at the theatre.

Sutro, Gibbs and Pointer had all come to Victoria from San Francisco in 1858, when the Fraser gold rush lured thousands of people north. For Sutro, it was a chance to make some money, while for Gibbs and Pointer, Victoria represented a chance to escape some of the racism they endured in California.

Gibbs had helped organize the emigration, which started in April, and made the trip north in June. He and his business partner, Peter Lester, opened a store that was said to be the first in Victoria not run by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

He was elected to Victoria city council in 1866, representing the James Bay ward, and helped push for British Columbia’s confederation with Canada.

After dissolving his partnership with Lester, Gibbs became involved in coal mining in the Queen Charlotte Islands, and had 50 men working for him.

With the end of the Civil War, many of the American blacks in British Columbia returned to the United States. Gibbs left in 1869, and by 1871 was working as a lawyer in Arkansas. He was a delegate to the Republican national conventions in 1880 and 1884 and held a variety of government and judicial positions over the years.

Gibbs served as the American consul in Madagascar from 1897 to 1901, and then became the president of a bank in Little Rock, Arkansas. In his autobiography, Shadow and Light, he wrote fondly of his time in Victoria.

Pointer remained in Victoria, staying active in business with a clothing store, and died here in 1903 at the age of 81.

A few years after the flour incident, Sutro returned to San Francisco and became a banker. One of his cousins was one of the most prominent businessmen in California at the time.