Ombudsperson Jay Chalke’s office investigates complaints from citizens about the services of 1,000 British Columbia public bodies.

But there is an important one that is missing: BC Ferries.

This year, the beleaguered ferry corporation received a $500-million infusion from government and went through an executive shuffle. The management-heavy company continues to grapple with staffing shortages that have delayed or cancelled sailings.

In 2003, the BC Liberal government transformed it from a Crown corporation into a private company with one shareholder: the government.

“One of the things that they did was they specifically provided in the Coastal Ferries Act that the Ombudsperson Act does not apply to things done under the Coastal Ferries Act,” Chalke said in an interview.

“So we don't have jurisdiction. We do have jurisdiction over the ferries commissioner, but we don't have jurisdiction over BC Ferries itself. I do think that the public have a right to seek some sort of external complaint mechanism and it's something I'd like to see returned at some point in the future."

The Office of the Ombudsperson isn’t facing any shortage of requests for help. There were 7,323 complaints and inquiries last year, with 1,367 files assigned to an investigator, according to the annual report.

The main reasons for complaints? Citizens disagreed with public body decisions or outcomes (1,828 files), process or procedure (1,611), or communication (978). ICBC attracted the most attention (493 files), followed by the Ministry of Children and Family Development (381) and Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (380).

Chalke said that his office has seen an increase in complaints about local governments, Crown corporations and health authorities.

The report said a third of files are closed in 30 days and 30 per cent in up to 90 days. But 16 per cent take up to six months and six per cent need between six months and a year to resolve. Chalke said complaints that are urgent and relate to life, health or safety get immediate attention, but he acknowledged backlogs have developed because government has become bigger and citizen complaints more complex since 2020.

“We have had the non-urgent assignments down to as short as two weeks a few years ago, but the pandemic has definitely had an impact,” he said. “Instability in public services – we investigate 1,000 public bodies – but you probably can't think of one that didn't change its service delivery during the pandemic.”

The office was allotted $12.8 million for operations this year. On Oct. 25, Chalke tabled his funding request for next year to the B.C. legislature’s Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services. He is seeking $14.8 million for each of the next three fiscal years. That includes an additional $692,000 for inflationary wage increases, $244,000 for Indigenous services and $146,000 for outreach.

“Lots of people don't know much about an ombudsperson’s office, it's a weird Swedish word,” Chalke conceded.

Sweden pioneered the ombudsman concept in the early 19th century. Canada’s first was at Simon Fraser University in 1965.

B.C. was the second-last Canadian government to appoint an independent ombudsperson in 1979.

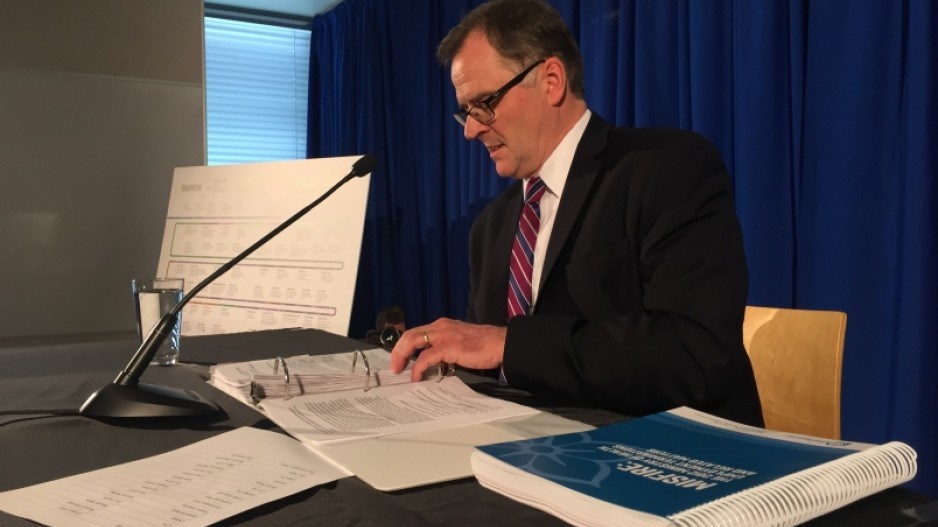

Chalke’s office also takes on complex investigations that sometimes have a lasting impact. One of the most famous – 2017’s Misfire – examined the unjust firings of Ministry of Health researchers and included a key recommendation to enact whistleblower protection.

B.C. was the last province to do so and Chalke has overseen the gradual implementation of the Public Interest Disclosure Act (PIDA). By the end of next year, when post-secondary employees are included, 300,000 public employees will be covered.

The act protects workers when they disclose wrongdoing internally or to come to the ombudsperson if they are more comfortable doing so.

“A lot of the time that I spend talking to leaders of public bodies who are about to be covered by the Act, I say, ‘This is your opportunity to really speak up as an organizational leader about the value of integrity and the importance of speaking up and welcoming your employees who speak up when they see something wrong,” Chalke said.

Chalke said PIDA does not yet cover local governments, but hopes that will be raised when a legislature committee is struck next year to undertake the statutory, five-year review of the ombudsperson’s enabling legislation.

After July’s Time to Right the Wrong report, Chalke said he was encouraged that the government will finally apologize to the children of Sons of Freedom Doukhobors, the religious group that survived confinement in New Denver between 1953 and 1959. He still hopes the government includes financial compensation.

Chalke found that the Ministry of Children and Family Development misled a 17-year-old in foster care about post-secondary education support eligibility and failed to advise her that she had a right to legal advice. But September’s Misinformed report did not result in government accepting recommendations.

“That doesn't happen very often in our world,” he said. “I will say that the only other time, and I've been the ombudsperson now for more than eight years, I did a report with respect to WorkSafe[BC], and that's the only other time that I've had a report where government has been as unwilling as they were in Misinformed to address our recommendations.”

The Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness was decidedly more receptive to Chalke’s early-October Fairness In a Changing Climate report on the wildfire and flood emergency support programs in 2021. That report found programs were outdated, under-resourced, inaccessible and poorly communicated. The NDP government promised to do better on multiple fronts.