With half a million mail-in ballots still being counted, the exact seat totals from last Saturday’s election remain uncertain. But what we do know is that the NDP won an outright majority, and a crushing one at that.

If the count remains as it stands, John Horgan and the NDP will have 55 seats, a gain of 14 and an all-time high for the party.

Andrew Wilkinson’s B.C. Liberals will lose 12 ridings, leaving them at 29. And Sonia Furstenau’s Green party will have three seats, the same as they won in 2017.

The big question is what happens now. Wilkinson has already accepted the voters’ verdict and announced he will step down as soon as a replacement can be found.

While there is no getting around the fact that he led a lacklustre campaign, let’s grant him this as he departs. Wilkinson is an honourable and decent man who would have made a good premier. But he ran into an immovable barrier.

From the outset of this election, the only serious concern on people’s minds was the COVID-19 pandemic, and the NDP owned that issue.

Furstenau’s job is not at risk. The party’s vote declined slightly, and with the NDP no longer dependent on Green support, it’s hard to see what meaningful role remains. Nevertheless, none of that is Furstenau’s doing. Her mission now is to use her personal popularity to boost the party’s standings, and hope for better times.

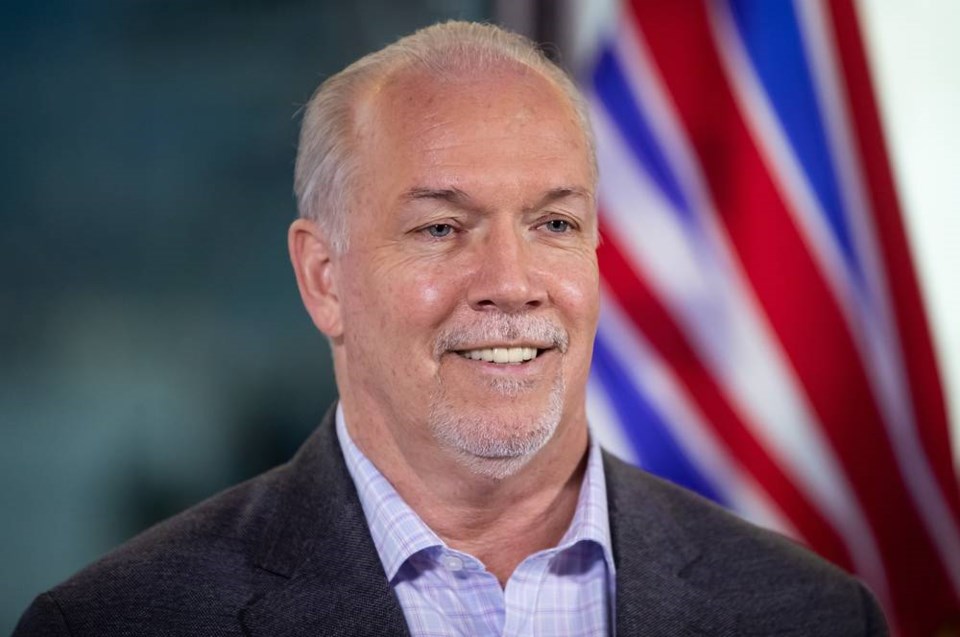

Ironically, though he pulled off a historic victory, becoming the first two-term NDP premier, Horgan’s position is more complicated than it might appear.

Previously, as leader of a minority administration, he could demand caucus support and get it. Any defections would have brought his government down.

Former premier Glen Clark enjoyed a similar degree of authority. After taking over from Mike Harcourt, and narrowly rescuing his party from near-certain defeat, he ruled with an iron hand. His word was law.

But Horgan now has that most delicate of tasks — guiding an NDP caucus overflowing with large personalities and demanding to be heard.

And he must not only rule, he must reward. There were 20 ministers and eight parliamentary secretaries in the outgoing government, along with various committees and task forces to be chaired.

With only 41 MLAs, that meant jobs for nearly everyone. But now that the caucus has swollen to 55, it seems a near certainty that some members will have to be left out in the cold.

It’s not the Liberals or Greens Horgan must worry about: It’s being stabbed in the back by a mutinous rump in caucus that feels disrespected and ignored.

One solution is to add a host of new ministries. This has been done before. Horgan himself divided the Health Ministry by setting up a parallel department of mental health and addictions.

Gordon Campbell, who had an enormous caucus to satisfy, created a ministry of health planning, separated from the parent health department for no other reason than to give a needy MLA employment.

More troubling, Horgan must also be concerned that with a parliamentary majority assured, the activist wing of his party will push for the kind of spendthrift and doctrinaire polices that ruined the NDP in the 1990s. We already know his government is headed for a deficit in the $14 billion range next spring. But that money is already either spent or spoken for.

The premier’s immediate task won’t likely be retiring that deficit. It will be preventing it from growing any larger.

And this is the real challenge he faces. Once the COVID-19 crisis passes, can he steer a path back to financial stability? During the NDP’s 10 years in office during the 1990s, there were only two balanced budgets, and one of those was razor thin.

This led to a general belief that the party could not be trusted on money matters. The result was an electoral wipeout, and 16 years of Liberal rule.

For now, that suspicion has been set aside. But if four years from today, huge deficits persist, and still more loom ahead, the ghost of earlier years will return.

To slay that ghost, Horgan must show his caucus and his party that he’s in charge.