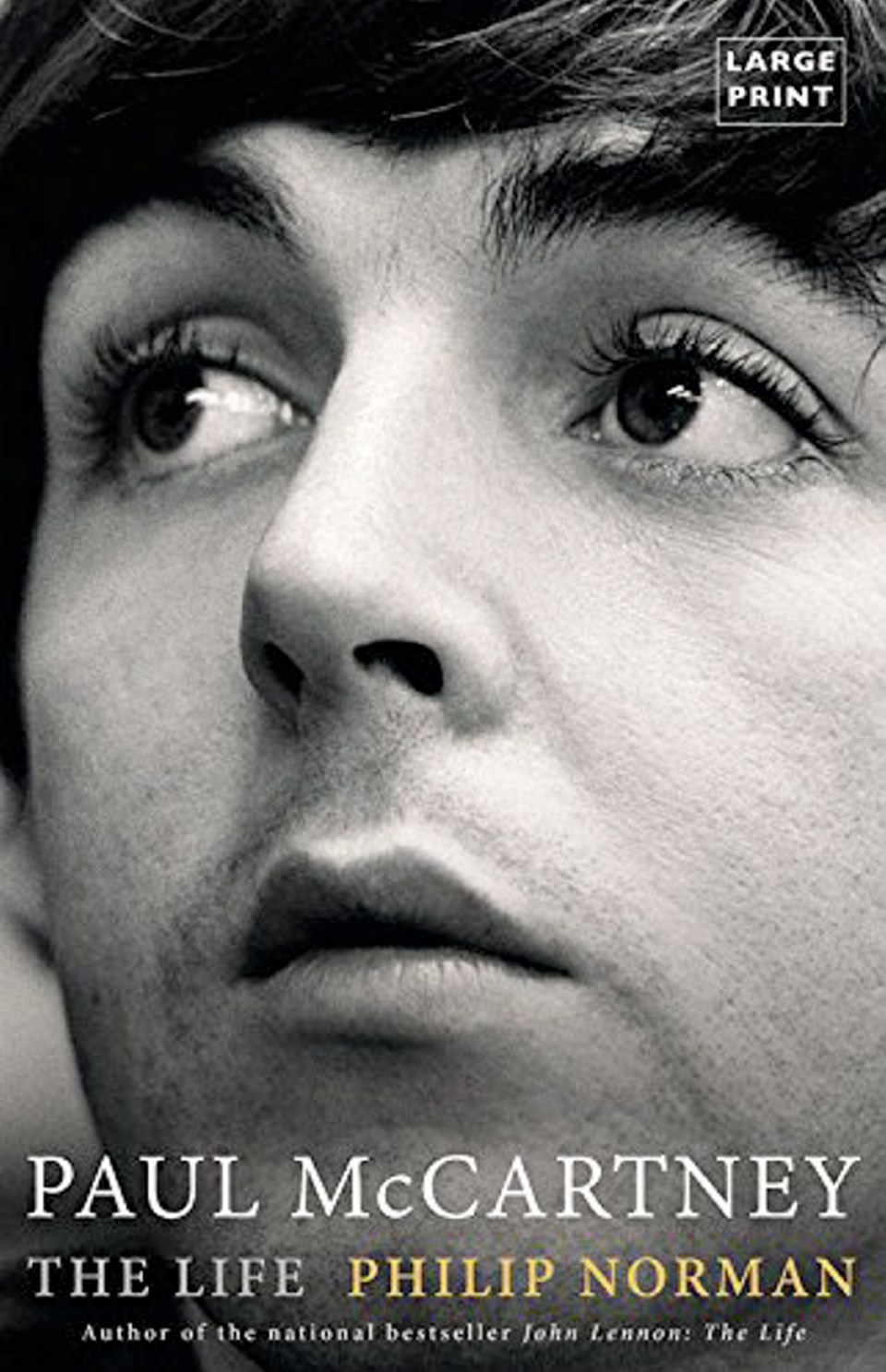

Paul McCartney: The Life

By Philip Norman

Little, Brown, 853 pp., $40.50

Behind the double thumbs-up, impish smile and round, half-moon eyes lies a Paul McCartney more complex than public perception lends itself to.

As biographer Philip Norman writes in Paul McCartney: The Life, McCartney is more than just the “cute Beatle” thumping away on a left-handed violin-shaped bass or the elder statesman of rock who continues to sell out stadium concerts lasting more than three hours. McCartney is, in fact, a “workaholic and perfectionist who, despite his vast fame, has been underestimated by history and who, despite his undoubted genius, is in his own way as insecure and vulnerable as was his seeming total opposite, John Lennon.”

That’s quite a turnaround from Norman, the author of several music biographies including the excellent John Lennon: The Life. Norman’s seminal 1981 biography of the Fab Four, Shout!: The Beatles in Their Generation, was on the receiving end of criticism for its “over-glorification of Lennon and bias against McCartney,” notwithstanding his pronouncement that Lennon was “three-quarters of the Beatles.”

If apology can take the form of biography, Paul McCartney: The Life is it and, thanks to “tacit approval” from McCartney to interview relatives and close friends, Norman delivers the most thorough and insightful biography of Paul McCartney to date.

Ruminations on the Beatles already fill the pages of countless books and websites, which is one reason why the success of Norman’s book lies not in its retelling of stories about performing Eddie Cochran’s Twenty Flight Rock or gruelling, Preludin-fuelled nights on Hamburg’s Grosse Freiheit and Reeperbahn streets, but in its depiction of McCartney as a son, friend, lover, avant-garde enthusiast, divorce plaintiff, vegetarian activist, DIY farmer and marijuana aficionado.

Some of the book’s best moments depict McCartney’s relationship with his father, Jim (the man who told his son it should be “She loves you, yes! yes! yes!”), and the lifelong influence his father had on him: “With Wings, his drive to reinvent himself … often gave way to a rather touching desire to please his father” by including songs that reflected his father’s taste in music.

On the Beatles’ breakup, Norman details the consequences of Allen Klein’s disastrous management and how McCartney was often on the losing end of three-against-one arguments over finances, album releases and his doubts about Klein: “Even the best-informed commentators knew nothing about the ostracism, marginalization, back-stabbing and humiliation within the band that he’d endured over the past months, yet still gone on trying to hold it together.”

Yet, McCartney at times could also be callous, bossy and demanding, and not just his in-studio domineering over George Harrison and Ringo Starr, each of whom briefly quit the band as a result. Apple Corps execs grew accustomed to “the bollockings he could deliver … and his way of emphasizing points with … pokes of a forefinger.” When first wife Linda began interviewing for a ghostwritten autobiography, McCartney’s hostility to a project that might shed light on their blissful marriage resulted in a shout of: “There’s only one effing star in this family!”

And, even into his 70s, McCartney is “still galled,” Norman writes, to see the order “Lennon-McCartney” on compositions that Lennon had little or nothing to do with.

Norman’s excellent insight into McCartney’s interest in the avant garde — which the author convincingly argues was far greater and pre-dated Lennon’s — is surpassed by his account of McCartney’s nine-day jail sentence for carrying marijuana into Japan in 1980.

Held at Kosuge Prison, prisoner No. 22 was awoken at 6 a.m. each morning for roll call, rolled up his thin sleeping mat, tasked with cleaning his 10-by-14-foot cell with a miniature dustpan, and was “terrified of being raped.” Two things helped McCartney survive the ordeal: entertaining his fellow inmates with a cappella versions of Yesterday and old standards beloved by his father, and the fierce “competitiveness that the other ex-Beatles knew so well.”

Such stories add up to make Paul McCartney: The Life an honest account of one of the most influential people of the 20th century — all without whitewashing or sensationalizing.

For everything the book excels at, however, there are some mistakes and odd phrases. McCartney’s expansive musicianship is deserving of its own book, and, typo or not, misidentifying the iconic Hofner 500/1 bass as “550/1” is a cardinal sin in the land of Beatles gear.

Norman’s occasional use of throwaway lines can frustrate as well. Writing that Wings was McCartney’s “creation of a band as big as [the Beatles had] ever been” is a bizarre claim — if not a laughable one — by any measure. Further, declaring that the “others really were just ‘sidemen for Paul’ as he pronounced their collective epitaph” on Abbey Road track The End is an odd way of describing a song that features Ringo’s one and only Beatles drum solo and Paul, George and John trading fuzz-drenched guitar licks.

But for each annoyance, Paul McCartney: The Life is loaded with wonderful passages, fascinating stories and cracking humour. In all, Paul McCartney: The Life is a largely masterful account, the kind of biography fitting McCartney’s continued prowess and genius.

Or, as McCartney said at the end of one Beatles take: “Keep that one. Mark it ‘fab.’ ”