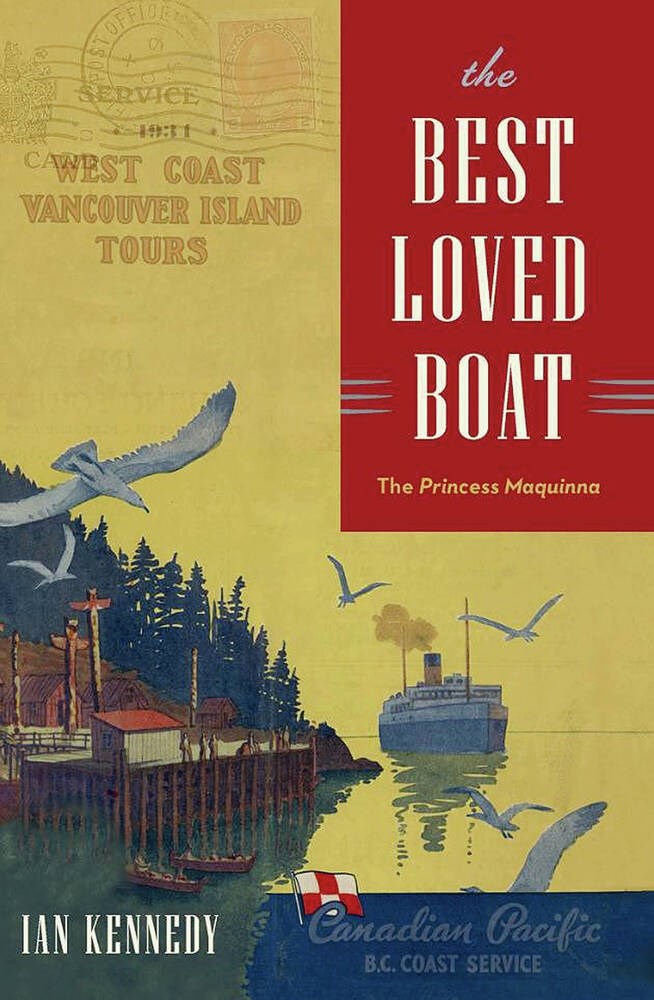

The Best Loved Boat: The Princess Maquinna

By Ian Kennedy

Harbour, 240 pages, $34.95.

Reviewed by Dave Obee

For 39 years, through two world wars, a depression and more, Princess Maquinna served the west coast of Vancouver Island as a proud member of the Canadian Pacific coastal fleet.

She was a lifeline for the west coast in those years before air or road access. Her passengers were varied — tourists, Indigenous people, missionaries, settlers, cannery workers, loggers, prospectors, politicians, business leaders and more.

Princess Maquinna stopped at up to 40 ports between Victoria and Quatsino Sound, close to the north end of the Island, during her seven-day runs. She was a cruise ship for her day, and for her purpose. Most of the people on board needed a place to sleep during their journey, so the ship had staterooms for those who qualified and lounge chairs for those who did not.

The “best loved boat,” as described by Ian Kennedy, was designed specifically for the rough conditions along our west coast. She was not pretty, but she was tough as nails — and a proud product of an Esquimalt shipbuilder.

Canadian Pacific already had ships serving Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle and the Gulf Islands when attention turned to the west coast of Vancouver Island, which had several major communities, many smaller ones, and less than adequate transportation service.

The west coast was rocky, with Pacific swells that meant riskier sailing than in the protected areas that the company already served. As a result, plans for the new vessel included a double hull, a low upper deck structure, and other features designed to make it safer and more comfortable in rough seas.

Those plans were submitted to shipyards in Britain as well as to William Fitzherbert Bullen’s B.C. Marine Railway Company, which used the old Royal Navy graving dock in Esquimalt to repair and build ships. Bullen’s bid of $250,000 matched those of the overseas shipyards, so he won the contract.

Princess Maquinna was notable as the largest steel steamship built on the coast. She was also notable for her name; other Canadian Pacific coastal ships carried the names of European princesses, but the new vessel was named for the daughter of Chief Maquinna, already a legend in the Nootka Sound area.

As a result, when she went into service in July 1913, she was the first CP ship to carry an Indigenous name.

By the numbers, Princess Maquinna was 1,777 tons, 244 feet long, 38 feet wide and with a draft of 17 feet. She could carry 400 day passengers, and had about 50 staterooms with upper and lower bunks.

But while numbers are interesting, they don’t tell the full story — and this is where Kennedy excels.

The Best Loved Boat is more than just the story of Princess Maquinna. Kennedy places her in time and in place, making his book a travelogue with snippets of local history and vignettes of local people along the coast.

He takes the reader on an imaginary voyage in 1924, allowing him to weave together a series of short stories along the way. His idea works, because it makes it much easier for everyone to envision what the service was like and what the coast was like, back when this princess ruled the waves.

The story is not always glowing. Asian and Indigenous passengers were not welcome to use the staterooms, for example, and in 1942 the ship was used to take Japanese-Canadians on the first leg of their journey to internment.

In simple terms: The Best Loved Boat is not simply the story of the boat, as loved as it was, but is about what the boat did. That is not a minor distinction.

By 1952, when Princess Maquinna was showing her age, she was already facing competition from new roads and new air routes. When her boilers gave out that September, it was decided that she was not worth saving. Stripped of her engines and much of her personality, she served as a barge for a decade before being scrapped in 1962.

But her spirit lives on, through the continuing interest in the ships that served us — and through books such as this one.

The reviewer is editor and publisher of the Times Colonist.