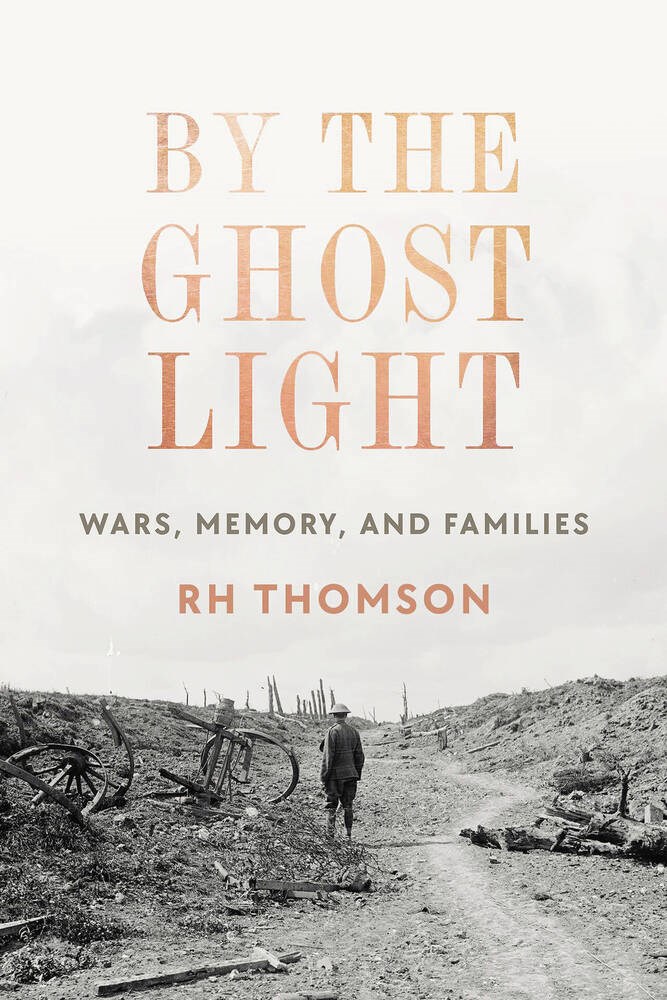

By the Ghost Light: Wars, Memories and Families by R.H. Thomson (Penguin Random House, 336 pages, $36.)

The name of Cuthbert Holmes is well-known in Greater Victoria, more than half a century after he left us, thanks to the Saanich park that was named in his memory soon after he died in 1968.

The lasting tribute to Holmes – better known as Major Holmes – is in recognition of his community accomplishments, including his work on behalf of the preservation of green space and improvements to traffic flow.

He was also successful in business. He joined his father-in-law Fred Pemberton’s real estate company, and renamed it Pemberton Holmes after he assumed the presidency in 1933.

Holmes was seriously wounded in fighting in Ginchy, France in 1916. He returned to Victoria to marry Philippa Pemberton, and they lived in France for a couple of years after the First World War, when Holmes was serving with the British section of the Supreme War Council during the negotiations at Versailles.

One of Cuthbert’s brothers was killed in the war; two of Philippa’s brothers were also lost in battle.

That is a local point of interest in By the Ghost Light: Wars, Memories and Families, a thought-provoking book by actor and author R.H. Thomson, a grandson of Cuthbert and Philippa.

It is but one of many points in this multi-layered book, which draws heavily on letters about the war experience, written by the author’s relatives, as well as his own research – but it is not specifically about either world war.

It is loaded with information on the Holmes, Pemberton, Stratford and Thomson families, but it is not about family history. Thomson takes the reader on a journey through war letters, to the ways we memorialize war, to Voyager 2, to executive compensation, to British Columbia’s 1862 smallpox epidemic – with a peek or two behind the curtains at theatrical productions thrown in.

By the Ghost Light is a natural project for Thomson, who has appeared in film and theatre across Canada, and has also worked on several history/arts projects. One of them was his play called The Lost Boys, based on 700 letters that his great-uncles sent home from First World War battlefields.

For the centenary of the First World War, Thomson built The World Remembers / Le Monde Se Souvient, an international exhibit now at the Canadian War Museum.

Thomson’s goal with The World Remembers was simple, but undeniably ambitious and probably impossible. He wanted to name every soldier who had died in the First World War — every soldier, regardless of which country they were from.

There was a story behind every one of those dead soldiers. There were more stories about the ones who survived, but were shattered, physically or mentally. And what about their families? It all matters.

Many communities found that it was difficult to accurately collect the names of local soldiers to include on a cenotaph. Thomson’s goal has been much, much greater than that, because different countries have different thoughts about noting those who had served. In some cases, lists are not available.

As Thomson writes, for his massive project to be successful, he needed to appreciate the war through the eyes of all the countries involved. Canadians were on the winning side, so our understanding of the war would not be the same as it was for the Germans or the Serbs.

Thomson’s background in theatre helped, because a good actor knows that to credibly portray a person, the actor must see the world from that person’s perspective.

Thomson gets into his characters, and does it well.

A couple of decades ago, I spent two weeks in France and Belgium, visiting battlefields and trying to understand the Great War, a war that defies logic in so many ways. I visited John McCrae’s grave in Wimereux, France; I visited the Vimy Memorial; I visited more war cemeteries and museums than I can remember.

I will never forget, however, that the head of the Passchendaele war museum had me sweating in fear as he walked me, along with the ghosts of the Canadian forces, into the village against the ghosts of German machine guns.

I am sure that Thomson and I probably crossed paths in the fields around Ieper (Ypres), but he has me beat.

For example: His great-uncle George Stratford was buried by the explosion of an incoming shell. Stratford was dug out alive, then carried on Private Ross’s shoulders to a casualty dressing station, where doctors declared him dead. It took Ross 12 minutes to get to the casualty station.

How does Thomson know that? Because he determined where the explosion happened and where the casualty station was. Then he carried a friend from one spot to the other, burdened by the weight and counting the minutes.

As he says, he needed the learn the details to appreciate what had happened.

The fighting just west of Passchendaele continued after George died, and the crosses and graves of the war dead were disturbed and scattered around. As a result, George Stratford’s name appears on the Menin Gate in Ieper, along with about 55,000 others whose final resting place is not known.

What is the meaning of the book’s title? Thomson writes that after a theatre performance, he often lingers by the ghost light – a single lamp left to burn all night – and he tries to hear the echoes of the characters’ lives that were played out that evening.

By the Ghost Light is a perfect title for a book that does not celebrate war, but forces us to reconsider it, look at it from several points of view, and best of all, attempt to hear the echoes of those who fought.

It is a complex, fascinating, and passionate book that, despite side journeys, never strays from the main theme of wars, memory and families.

Cuthbert and Philippa Holmes are both long gone – but R.H. Thomson, their grandson, is doing all he can to ensure that their wartime contributions, along with thousands of other Canadians, your families and mine, will never be forgotten.

The reviewer is editor and publisher of the Times Colonist.

-thumb.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)