What: 2020 DOXA Documentary Film Festival

Where: doxafestival.ca

When: June 18-26

Admission: $6-10 per ticket; $60 for a festival pass from doxafestival.ca or 604-646-3200 (tickets allow viewers to unlock a program for 24 hours for home viewing)

COVID-19 restrictions mean the 19th edition of Western Canada’s largest documentary film festival will be moved entirely online this year.

But with the pandemic-spurred rise in TV and film viewership, Vancouver’s DOXA Documentary Film Festival can expect a sizable audience for its 64 shorts and features, streaming online June 18 through June 26 on the festival’s website.

The lineup includes three documentaries with deep Victoria connections: two shorts by Victoria-raised director Carmen Pollard, and another shot in Victoria by Vancouver filmmaker Joel Salaysay.

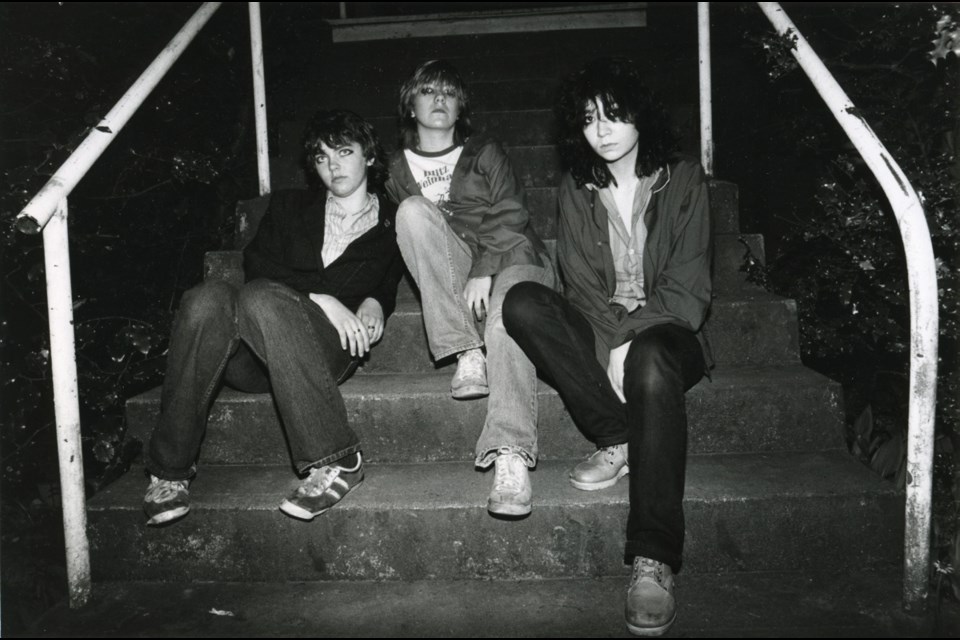

Red and Madame Dishrags, which Pollard made with partner Brock Ellis, formerly of Victoria group the Vinaigrettes, are bios of Vancouver’s Red Robinson, the most famous radio disc jockey in B.C. history, and the Dishrags, a key but little-known female punk group from Victoria.

The documentaries co-written, produced, directed and edited by Pollard are part of Dancehalls, Deejays & Distortion, a 10-part series Pollard made for Knowledge Network to celebrate the province’s music community.

With the series scheduled to air on the network in 2021, Pollard’s contributions — completed shortly before the festival’s submission deadline, when the pandemic was beginning to take hold — serve as a sneak peek.

Finishing the docs during the pandemic had its challenges, she said. “That is when I needed to be in the mix and in the room with the colourist, and suddenly [we] had all these restrictions that we needed to abide by.”

The documentary on Comox-born Red Robinson covers familiar ground — Robinson interviewed Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Buddy Holly and others during their heydays — but The Dishrags are considerably more obscure.

Turning a camera on the punk scene of the late ’70s was an obvious move for the 47-year-old filmmaker. Pollard is several years younger than the members of The Dishrags, but grew up in the same area of Central Saanich as members Chris (Dale Powers) Lalonde, Carmen (Scout) Michaud and Jill (Jade Blade) Bain. “I always admired them from a distance, but had never met them until I made the film.”

The Dishrags are considered the first punk band ever in Victoria, and one of the first all-female punk acts in North America. Following a move to Vancouver, the band opened for The Clash at the Commodore Ballroom in 1979, during the British band’s Canadian performance.

Pollard could have shot the modern-day interviews for Madame Dishrags at the hallowed hall, a popular concert venue to this day. But she chose to set the interview in what would have been the principal’s office in the band’s former Mount Newton High School in Saanichton, now home to Butler Concrete & Aggregate Ltd.

These were the humble beginnings for The Dishrags, who would become an influential act during their three-year run, Pollard said. “Jade talked about how much their high school experience influenced them to follow the punk rock ethos. It seemed obvious to us all that that was where we should shoot the film.”

Salaysay chose a setting for his documentary that was similarly close to home: His grandmother’s kitchen in Victoria. Three generations of the director’s family are the focus of Home Cooking, which explores Salaysay’s “elusive relationship” with his grandmother, who was born in China and speaks very little English.

Salaysay, who is of Chinese/Filipino descent, joins his mother, Hwee Ming Salaysay, and his 85-year-old grandmother, Kit-Kit Lin, in the kitchen for a cooking lesson. Through the process of making bak chang, a traditional rice-dumpling dish, he discovered as much about his grandmother as he did about his own culture.

“When people ask me the question, ‘What are you?,’ which is a question I get quite often, the practical answer is Canadian through and through. My only real connection to my [Chinese] heritage and that culture is the food that I was introduced to growing up. This was an opportunity to explore that.”

It was also a way to spend time with his grandmother and learn a recipe he didn’t know, Salaysay said.

“But I also learned about who she is and about her relationship with my mom. When I was growing up, these two people, who were very warm to me and my sister, were not always the warmest toward each other. I certainly learned a little more about the nature of their relationship.”

-thumb.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)