What: The Artist Herself: Self-Portraits by Canadian Historical Women Artists

Where: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

When: Opens Friday, continues to Jan. 3

Admission: $2.50, $11, $13 (free for children under five)

Thanks to Facebook, people are more open-minded as to what constitutes a self-portrait, art expert Alicia Boutilier says.

Boutilier is the co-curator of The Artist Herself: Self-portraits by Canadian Historical Women Artists — a new exhibit at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria featuring the work of 41 female artists.

Many items on display are not what most people consider “self-portraits.” There are conventional self-portrait paintings, of course. However, the exhibition also includes a vintage crazy quilt, an early 1900s sewing roll, a 19th-century sampler and an Inuit amauti (or parka).

There’s a painted cookie tin from the 1960s, created by Nova Scotia folk painter Maude Lewis. Boutilier contends even the interior of Lewis’s one-room home (apparently she painted on every available surface) can be viewed as a self-portrait of sorts.

And, Boutilier says, if people today are more accepting of such a notion, Facebook is a factor.

“I think now, people are more receptive to expanding the definition of self-portraiture because of the proliferation of selfies. We’re really exploding this notion of what visually can represent us,” says Boutilier, curator of Canadian historical art at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont.

She notes people on Facebook not only post selfie photographs, but portray themselves with a kaleidoscope of images, such as pets or meals. In this way, the definition of the self-portrait is expanded beyond the literal.

The Artist Herself arrives in Victoria following its opening exhibition this summer at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. Boutilier says this is the first significant exhibition in this country using the female self-portrait as a theme. As such, it’s a landmark in Canadian feminist art history.

Victorians surface several times in the exhibition. For instance, there are paintings by Emily Carr, as well as photographs by Hannah Maynard.

Carr’s Emily and Lizzie, painted in about 1913, is an early work showing the artist with her eldest sister. Carr portrays herself as a dark silhouette in contrast to her sister, bathed in light. This may indicate her sense of “psychic isolation,” Lisa Baldissera writes in the exhibition’s catalogue.

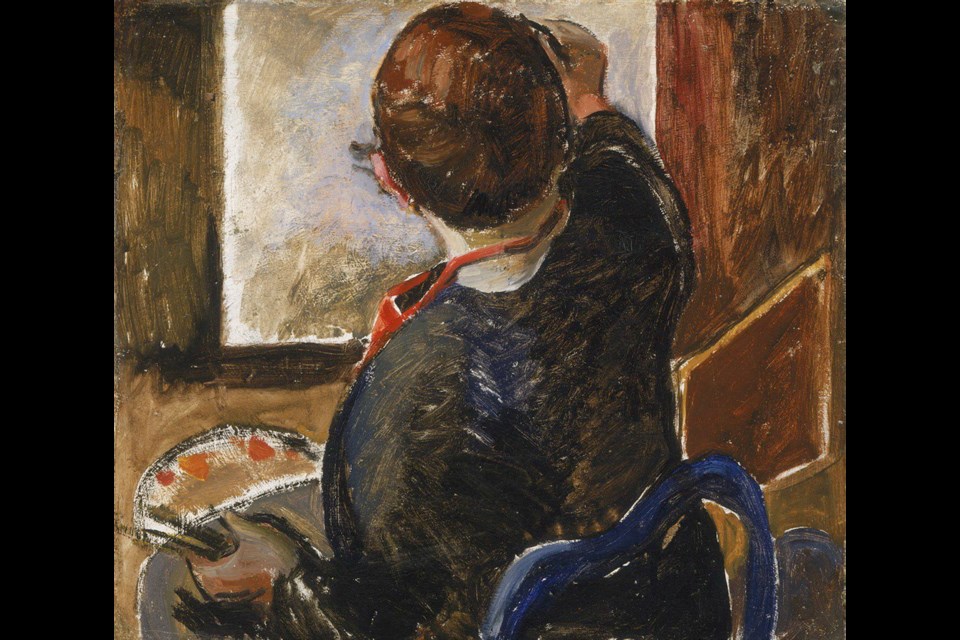

In an untitled self-portrait painted about a dozen years later, Carr presents herself in an even more unorthodox way. She is portrayed as an artist with brush in hand; however, the viewer sees only the back of her body and head.

“It’s very odd,” Boutilier says. “Some of the portraits are like that, either unintentionally or intentionally being self-effacing. Making themselves smaller, or showing the back of the head or being absent from their studio. I wonder if that speaks to a certain gender divide.”

Maynard, who was active in the late 1800s, was the Victoria Police Department’s first official photographer. Today, she’s known best for eccentric self-portraits that, using photographic tricks, showed her as multiple images in the same frame. Untitled (Tea Time) portrays two Hannah Maynards, identically garbed in Victorian dresses, having tea with one another. Meanwhile, what appears to be a painting of Hannah Maynard on the wall mischievously pours tea on one of the seated Hannahs.

Boutilier notes with such a photograph, Maynard satisfied social expectations of the time. Despite the zaniness of Untitled (Tea Time), she’s still dressed as a conservative matron. Another multiple-image self-portrait — Untitled (Winding Yarn) — shows Maynard doing embroidery, an acceptable practice for any respectable Victorian woman.

A highlight of The Artist Herself are items associated with Emily Pauline Johnson. Popular in the late 19th century, Johnson was a writer and performer who was the daughter of a Mohawk chief and an English woman.

She dubbed herself Canada’s Indian Princess. Dressed in a buckskin dress with a bear-claw necklace, she would recite poems. Then Johnson would change into a Victorian gown for her finale. (The exhibition in Victoria features her gown and a poster; however, the owners of the buckskin dress would not allow it to travel here because it is too fragile.)

Like Maynard, Johnson was clever enough to acquiesce to social convention while getting her own message across. She would play the part of the “Indian princess” — a romanticized notion expected by Euro-Canadian audiences. At the same time, her poetry exposed the plight of First Nations people to white audiences, a rare thing, especially coming from a woman.

The exhibition also includes works by Molly Lamb Bobak, Mary Hiester Reid, Florence Carlyle, Elizabeth Simcoe, Bertha May Ingle, Pitseolak Ashoona and Kenojuak Ashevak.

Boutilier and co-curator Tobi Bruce will lead a tour of The Artist Herself at the AGGV on Friday from 2 p.m.

to 3 p.m.

[email protected]

-thumb.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)