Proponents of British Columbia's move to provide free prescription contraception say the policy could spur other provinces to follow suit but a national plan would best serve people's reproductive needs and slash health-care costs overall.

Obstetricians and reproductive rights advocates say other countries, including the United Kingdom, already provide free contraception as part of their health-care plans.

One of those advocates is Grade 11 student Sophie Choong, who joined a campaign launched by a group called AccessBC to push the government to keep an election promise to provide free contraception.

She helped put up billboards on a highway in Victoria, home of the B.C. legislature, and was also involved in placing ads on transit in January.

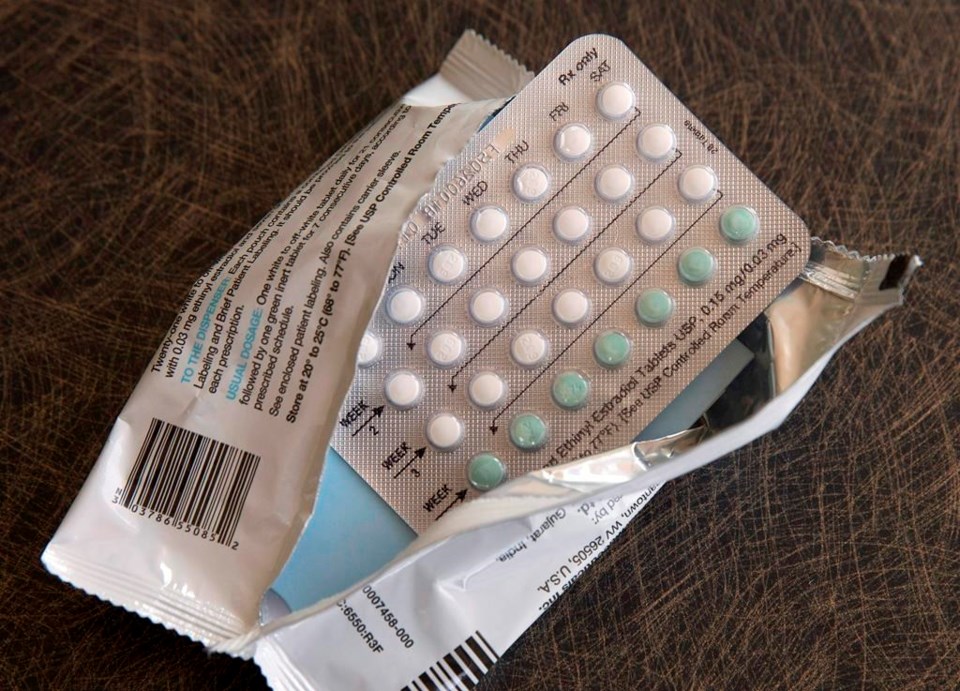

On Tuesday, Finance Minister Katrine Conroy announced in her budget speech that free prescription contraception would be available as of April 1 at a cost of $119 million over three years. The options covered will include oral hormone pills, contraceptive injections, copper and intrauterine devices and subdermal implants, along with so-called Plan B, also known as the morning-after pill.

Choong called that a "beacon of hope" for the rest of the country.

"There are many young people who do need access to contraception and that's just a reality," she said. "The other big problem is that many people don't have access to contraception because they don't get parental approval (to help pay) for it."

Teale Phelps Bondaroff, a spokesman for AccessBC, said the group has been pushing for free contraception in B.C. for six years and those fronting campaigns elsewhere in Canada, including Ontario, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, see B.C.'s decision as a catalyst for potential change in their jurisdictions.

"We've had tens of thousands of people from across British Columbia participate in multiple waves of letter writing," he said. "We lobbied politicians directly from all sides of the political spectrum."

Dr. Wendy Norman, family planning research chair with the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, worked to provide evidence to the B.C. government on the benefits of providing free contraception.

"We were able to conduct a door-to-door survey throughout the province and find out what people needed and put this into a cost-effective model," Norman said of the Contraception and Abortion Research Team (CART), a network of researchers and clinicians that she founded.

"We conducted a sexual health survey throughout the province, knocking on people's doors to ask them, would they tell us about their sexual health needs and behaviours and intentions? By using that data, we were able to see that 40 per cent of pregnancies were unintended, that people who wanted to prevent a pregnancy weren't able to afford their contraception."

The cost of preventing unintended pregnancy was the biggest challenge many cited, Norman said.

"If those contraceptives had been available to them, the savings to the government would be something in the order of $27 million a year," she said of the survey done in 2015. The results were presented to the B.C. government in 2018.

"In fact, when you want to try to manage your fertility, the most effective methods are the most expensive upfront for a patient," she said.

For women who may already be struggling with other health issues such as addiction and mental health, one of the potential outcomes of unintended pregnancy is complications requiring hospitalization and neonatal intensive care for the baby, Norman said.

"The system may be helping that family as they move forward. But that's not even included in those cost-effectiveness (models)," she said.

Along with doctors, B.C. pharmacists will later this year have the power to prescribe contraception and are trained to counsel people on hormonal contraception, said Norman, who is also a professor in the department of family practice at the University of British Columbia.

Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries already provide free contraception, she said.

The federal government is funding a national sexual health survey to be managed by Statistics Canada.

"We hope we can get the data for all the jurisdictions to be able to move forward and understand how best to serve health equity through public policies that support people to time and space the children that they'll have," Norman said.

Dr. R. Douglas Wilson, president of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, said support for "reproductive prevention" should be a national priority rather than provinces coming up with their own policies because the emotionally charged issue of abortion means access varies across the country.

"Some provinces are very conservative and have stronger opinions about the provision of abortion services. If we're looking at balancing health-care dollars, it's much better to prevent pregnancies than to have to deal with unwanted pregnancies that require both physical and potential emotional trauma for a termination of a pregnancy," he said.

"It really is the best thing to allow women and men to prevent pregnancies rather than to have to deal with the consequences of an unwanted pregnancy."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 1, 2023.

Camille Bains, The Canadian Press

Note to readers: This is a corrected story. An earlier version said Norman is an associate professor, instead of professor.