Canada’s federal minister of the environment has recommended an emergency order to halt logging on 2,500 hectares of old-growth forest, home to the last known wild spotted owl, Glacier Media has confirmed.

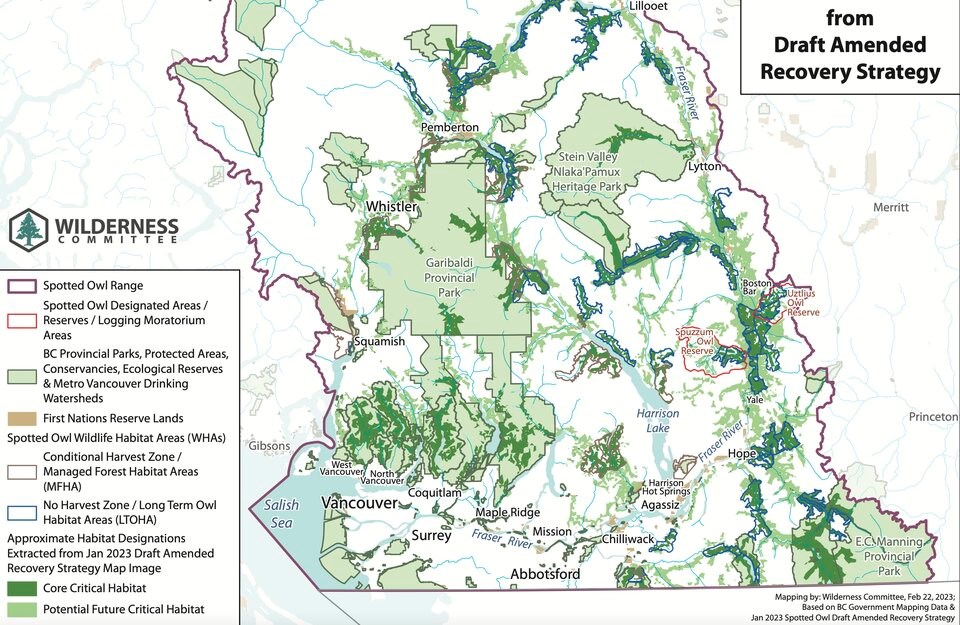

The recommendation from Steven Guilbeault, which still needs cabinet approval, would protect two patches of forest near Spuzzum and Utzlius creeks in the Fraser Canyon. Core critical habitat for the northern spotted owl stretches from the Lower Mainland, through the Squamish Valley to Whistler, Pemberton, down the Fraser Canton and south past Hope.

But many of those areas have seen high-intensity logging over the past two decades as the province has missed conservation deadlines and green-lighted harvesting of old-growth stands, said Charlotte Dawe, a conservation and policy campaigner with the Wilderness Committee.

“Ever since 2003, we’ve known the spotted owl has been at risk of extinction,” said Dawe. “There’s one spotted owl left that we know of.”

“This is the federal government saying ‘enough is enough.’”

About 40 centimetres tall with dark plumage, dark eyes and no ear tufts, the northern spotted owl ranges from southern B.C. through Washington, Oregon and into northern California. A subspecies of the spotted owl, it was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2008.

The recommendation to protect two swathes of land near Spuzzum Creek and Utzlius Creek come after an "imminent threat assessment" examined the impact logging had on the owl’s habitat, according to a letter from Daniel Wolfish, director general of the Canadian Wildlife Service’s regional operations directorate.

The threat assessment indicated logging “poses an imminent threat to the survival of the species” and that 2,500 hectares of land in the area have a “high potential to be harvested over the next year,” according to the letter seen by Glacier Media.

Allowing the logging of the two areas would make recovery of the species “highly unlikely,” added Wolfish.

If passed, the emergency protection order would be an intermediate step in a federal recovery strategy currently open to public consultation.

In an emailed statement, Guilbeault said he is “of the opinion that the Spotted Owl species faces imminent threats to its survival and recovery.”

“I am aware that British Columbia is considering extending the temporary timber harvesting deferrals in the Spuzzum Creek and Utzlius Creek watersheds. These deferrals are essential for the survival of the species,” he added.

Guilbeault said the latest threat assessment was made with the objective of recovering the spotted owl’s Canadian population to at least 250 individuals.

A spokesperson for the B.C. government wasn't immediately available for comment.

Recovery of the species is possible through breeding programs and introduction of wild owls from the United States, says Dawe. But first, the owls need intact old-growth forests, where they nest in woody cavities and broken large diameter trunks.

A few patches of unconnected old-growth forest won't be enough for the northern spotted owl to survive. That's because the owl species only flies over old-growth canopy, and when fledglings are born, they need connected forest corridors to spread out into new territory.

“Those new owls can’t stay in the same polygon as their parents. They’ll kill each other,” said Chief James Hobart of the Spô'zêm First Nation, whose territory overlaps with the Spuzzum Creek watershed.

Hobart says at one point, Environment Canada, the province and his nation were in the same room speaking about this same thing: protecting vast swath of forest for the spotted owl.

Then “things slowly started to go sideways.” Hobart says the province granted some logging companies permission to harvest in old-growth corridors flagged for owl habitat.

“This move with the federal government is huge,” said the chief.

For the Spô'zêm people, the northern spotted owl is more than one data point on a growing list of endangered species.

Members of the Fraser Canyon First Nation would traditionally pick up the owl's feathers and use them for their most honourable ceremonial regalia.

“They are more respected than the bald eagle,” said Hobart.

“To us, part of the reason they have that value is they are messengers of the forest. They communicate the health of the old growth.”