It’s the 25th anniversary of the 1994 Commonwealth Games, and a whole generation has no recollection of the moment many long-timers consider a seminal part of the region’s past.

The joke used to be that many of the 14,000 volunteers would wear their Easter-egg coloured uniforms until they became worn and threadbare. Indeed, for many years after, they could be found on the backs of former volunteers or in thrift or second-hand stores.

But 25 years is a long time.

A quarter-century ago, Jean Chrétien was a year into being prime minister and Bill Clinton in his first term as U.S. president. Prince William was 12 and Prince Harry nine. Hong Kong was still in the Commonwealth and South Africa was just making its return after apartheid. The Vancouver Canucks barely missed winning the Stanley Cup in Game 7 at Madison Square Garden. A white Bronco raced down Los Angeles freeways with the police in pursuit and the world watching.

You would be hard-pressed now to spot any 1994 Games clothing in passing (even those powder-blue 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics volunteer ski jackets are become scarce). But the event galvanized this city in a way few have.

Even the Games’ most high-profile critic, the late four-term Victoria mayor Peter Pollen, came around — to a point. “The Games were a joyous occasion, but boosterism is a poor direction for a city to take,” Pollen told the Times Colonist in 1998, giving in a little but still holding to his beliefs.

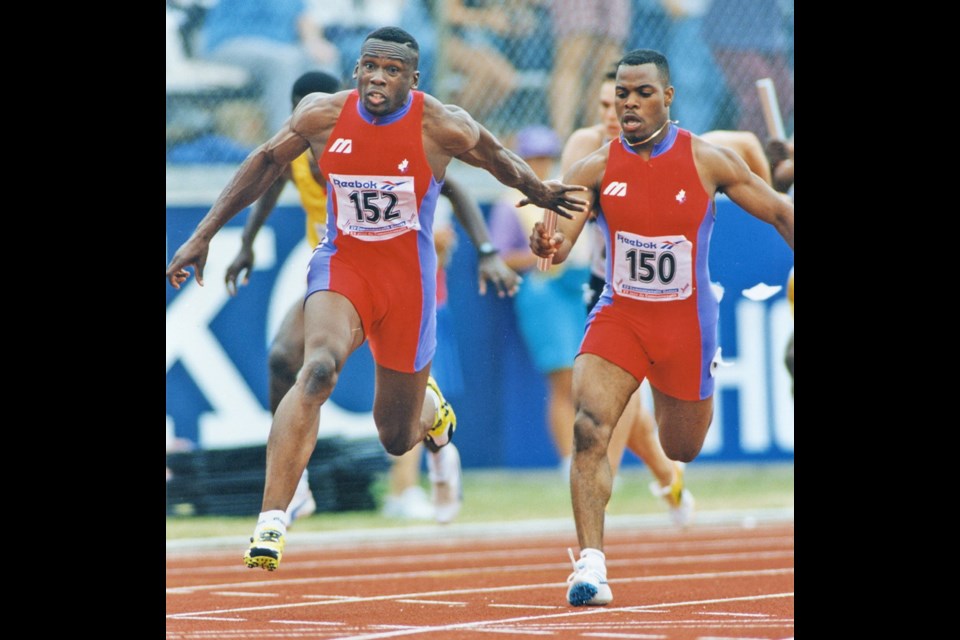

But a city that too often defines itself by what it shouldn’t be got a glimpse of what it could be. Hosting the 1954, 1962 and 1982 Commonwealth Games helped transform Vancouver, Perth and Brisbane from provincial backwaters to cities with broader, more international visions. The same could be argued of Victoria. The Games attracted 3,700 athletes from 64 countries and territories from Aug. 18-28, 1994.

Then there are the legacies. The $29-million Athletes Village, for example, is now a well lived-in townhouse complex, part of the University of Victoria’s residences.

Saanich Commonwealth Pool has gone on to host the likes of Michael Phelps in the 2006 Pan Pacific championships. It has produced Olympic medallists such Ryan Cochrane and Hilary Caldwell and continues to churn out medal-winning swimmers — right up to this month in the 2019 Pan American Games in Lima, Peru.

Velodromes are usually the lumbering white elephants of any summer Games. But the 1994 Games facility in Colwood has proven a success story.

The Island cycling community rallied to save it when it was threatened with destruction. Since then, it has produced 2019 Lima Pan Am Games silver-medallist Erin Attwell, 2012 London Olympic bronze-medallist Gillian Carleton, 2015 Toronto Pan Am Games gold-medallist Evan Carey and 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games bronze-medallist Jay Lamoureux.

There is also the nearly $20-million legacy fund that continues to fuel Canadian national team athletes through the 94 Forward committee.

Team events — even in such popular Commonwealth sports as field hockey and rugby sevens — weren’t part of the 1994 Games. Triathlon and mountain biking had yet to be introduced to the Olympics. And yet the ‘94 Games are helping influence those sports through the fund.

But what happened a quarter-century ago was much more than a sporting event. The medal ceremonies, at night in the Inner Harbour, were joyous — think Symphony Splash crossed with Canada Day and then turbocharge even that.

The question will be asked whether we should attempt to do it again. The idea has already been politely rejected by the current provincial government. With the reverberations of 2010 long muffled, it said no to B.C. Place hosting games in the 2026 soccer World Cup, and no to a Victoria bid for the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

Even Calgary, host of the 1988 Olympics, voted 56 per cent against bidding for the 2026 Winter Olympics in a referendum last year, even thought the Games were Calgary’s and Canada’s for the taking. Meanwhile, the 2015 Toronto Pan Am Games came and went without much national notice and were no more than a blip.

The topic will come up again, as Canada is the sentimental choice for the 100th anniversary Commonwealth Games in 2030. The first Games were held in Hamilton, Ont., in 1930.

Past host cities Hamilton, Edmonton and Victoria have been talked about as possible hosts as the nascent bid process begins. But will the Canadian public mood swing back to major public sporting spectacles?

Twenty-five years on, that is really the question — especially in light of the ridiculous cost escalation, which topped out at the $51 billion Putin put into the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. The 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics opening ceremony alone cost just under the entire $162-million budget of the Victoria Games.

In light of all those epic pictures of unused and decaying post-Olympic facilities in Athens and Rio, even the IOC is asking host cities to put on more modest Games.

What seems to be more popular now are niche or boutique special-interest Games that cost a fraction of major Games. The City of Victoria was all over the bid for the 2020 North American Indigenous Games, which utlimately went to Halifax. And the site visit is taking place this weekend regarding Victoria’s bid for the 2022 Invictus Games for injured military personnel.

Whether the appetite again returns for such mega events remains to be seen. But good or bad — from Montreal’s staggering debt to Sidney Crosby’s golden goal — they have left indelible imprints across the Canadian landscape.