They’re called “key biodiversity areas,” and seven swaths of land across British Columbia — including Tofino’s mudflats, the Trial Islands and Fort Rodd Hill — now have that international designation, which is meant to prevent the decimation of wild animal and plant species before it’s too late.

Under the key biodiversity area umbrella, more than a dozen conservation organizations have identified, mapped and helped monitor more than 16,000 key habitats around the world — from terrestrial forests, deserts and grasslands to mountains, marshes and reefs.

The global database allows scientists, conservationists and policymakers to prioritize what species need the most help, says Birds Canada’s James Casey, a Fraser River estuary specialist.

“It’s a massive transition that's happening,” said Casey of the KBA classifications.

Casey added that by mapping out the habitats of Canada’s most threatened and endangered species, individuals, non-profits and governments can “drive conservation on the ground.”

Unveiled to the public this month, the designation now includes a patchwork of 73 key biodiversity areas across the country. More than 900 more locations are currently being assessed to be added in the coming years.

Some of the biggest tracts of land identified as KBAs in Canada include a whooping crane nesting area bordering Alberta and the Northwest Territories, a large part of the Canadian shoreline of Lake Superior in Ontario, and a stretch of rugged mountains, boreal forest and Arctic tundra in the Yukon known as Tombstone Territorial Park. Home to grizzly bears, caribou and a rare mountain lemming, the park also shows evidence of human use dating back 8,000 years.

The designation is not legally binding, but Casey says the more data fed into the maps, the better groups like Birds Canada, the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada and NatureServe Canada — which make up Canada’s KBA Secretariat — can make the case to governments that they should conserve critical habitat.

Citizen scientists play a key role, largely by uploading animal or plant sightings through apps like iNaturalist. But while that data is vital for conservation, others are warning of staggering losses of wildlife.

A steep decline

Last month, the latest State of the World’s Birds report warned 49 per cent of global bird species (5,412) are in decline, with another one in eight critically endangered and under threat of extinction.

The slide matters, not only for bird populations, but the rest of ecosystems they are connected to.

“By collating and analyzing bird data, we not only understand their condition, but also gain an unparalleled insight into the health of the natural world as a whole,” states the report.

“In effect, birds act as barometers for planetary health, allowing us to ‘take the pulse of the planet.’”

One global study published this month found wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69 per cent since 1970. The staggering rate of loss includes 5,320 species of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians, but not spineless invertebrates.

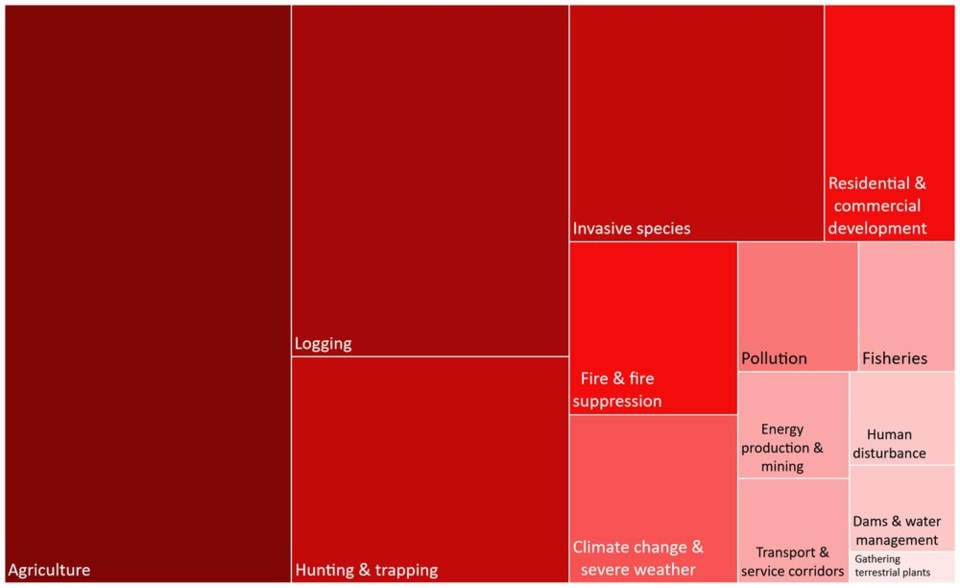

When it comes to birds, species decline is overwhelmingly caused by human activity: destroyed habitat due to expanding agriculture and logging, the rise of invasive species, residential and commercial development, and ongoing hunting and trapping practices.

Another threat, and one that’s most prevalent in Canada, warns the State of the World's Birds report, is human-driven climate change.

Many threats build on one another, with deforestation and climate change increasing the risk of extreme wildfire, the report notes.

When it comes to birds, species decline is overwhelmingly caused by human activity: destroyed habitat due to expanding agriculture and logging, the rise of invasive species, residential and commercial development, and ongoing hunting and trapping practices.

Another threat, and one that’s most prevalent in Canada, warns the State of the World’s Birds report, is human-driven climate change.

Many threats build on one another, with deforestation and climate change increasing the risk of extreme wildfire, the report notes.

With birds often touted as bellwethers for environmental change, perhaps it’s no surprise that their sanctuaries make up a vast proportion of the areas identified as critical habitat under the Canadian KBAs.

In B.C., the estuary of the Lower Fraser River is among the province’s most important habitats that require protecting, according the to KBA mapping project.

During the spring breeding migration, over a million western sandpipers have been observed foraging on the intertidal mudflats surrounding B.C.’s biggest cities.

“Any given year, you get 30 to 40 per cent of the world population of sandpipers using it as a stopover site oversight,” said Casey. “That makes it super important.”

“It is Western Canada’s most significant bird site.”

But at the same time, Casey added, the Fraser delta region is interlaced with Western Canada’s largest urban population and the largest industrial port.

“We’ve got Roberts Bank Terminal 2 project, which is putting the world population of western sandpipers at risk, as well as threatening southern resident orcas and salmon,” he said.

Meanwhile, invasive species like the European green crab are destroying many of the shellfish beds several migratory birds rely on to sustain them on their journeys. And across Canada, domestic cats are thought to kill between 100 and 350 million birds every year.

Add climate change to the mix and more than 100 species of birds across the Metro Vancouver region are facing less than a 50 per cent chance of surviving over the long run, says Casey.

The importance of conserving B.C.’s wetlands and intertidal mudflats, however, is not limited to the Metro Vancouver area.

Another B.C. KBA surrounds the Vancouver Island town of Tofino, where six distinct mudflats support a rich community of plant and invertebrate life, which, in turn, sustains a massive migrating bird population.

Among the migrating birds are roughly 600,000 western sandpipers, which arrive in the spring to replenish critical fat reserves before continuing north toward Alaska.

Scientists have found there’s something hidden in the mud, said Casey.

In the past, researchers thought the sandpipers only fed on invertebrates in and on the mud. But recent studies have shown a handful of bird species — including the sandpipers — consumer large quantities of something called “biofilm” off the surface of the mud.

The thin mucous layer contains a number of single-celled plants and other micro-organisms. When spring meltwater comes into contact with the salty ocean, the micro-organisms are thought to produce essential fatty acids that act as fuel and flight-performance enhancers for the birds’ long migration.

The birds’ body and behaviour also appear to be carefully adapted to rely on the biofilm. With a bristly tongue “like Velcro,” they can consume up to 20 per cent of their body weight in biofilm every day, Casey says.

The sandpipers also appear to time their migration with the spring melt, scientists have found.

“If they don’t get enough fuel, they don’t successfully migrate that far,” said Casey.

Little-known species on the edge

So far, seven key biodiversity areas have been mapped across B.C., though Casey says he is working with the KBA Canada Secretariat to assess another roughly 100 critical habitats in the province.

Outside of the mudflats in Tofino and the Fraser estuary, here's a glimpse of where conservationists think B.C. needs to start paying attention to threatened and endangered species.

Little Quarry Lake

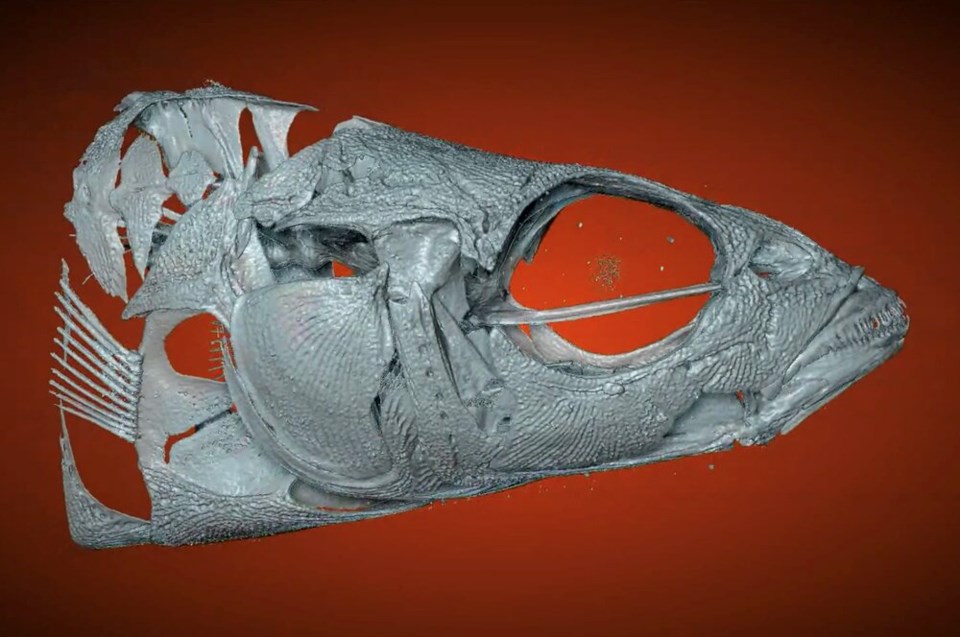

On an island off the Sunshine Coast, Little Quarry Lake has managed to keep the world out for a long time — long enough to support the evolution of a unique three-spined stickleback population.

At just over 20 metres deep and bounded by old-growth trees, the lake is only connected to the sea by a single high-angle stream. To keep the species alive in more than the pages of a book will require keeping outsiders out.

“Ensuring no invasive species are introduced is essential,” notes the KBA Secretariat.

Trial Islands

More than 160 kilometres south, off the southern end of Vancouver Island, lie the Trial Islands — five islets home to “exceptional assemblages of rare and endangered plant species,” including the “globally critically imperilled Garry oak” ecosystem, notes the KBA description.

Fort Rodd Hill

Nearby in the City of Colwood, Fort Rodd Hill’s Coastal Douglas fir and Garry oak ecosystems are “among Canada’s rarest,” notes the secretariat.

In addition to a number of imperilled plants, the woodlands and rocky bluffs offer a home to great blue herons, barn swallows and olive-sided flycatchers, a migrating consumer of flying insects assessed as threatened in Canada.

Pemberton

In the Coast Mountains, another area identified by the KBA Canada Secretariat is found north of Pemberton, where a junction of two ecosystems has produced a unique habitat and the only place in Canada where scientists have found a unique sub-species of sharp-tailed snake.

Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi'it (Tobacco Plains) Reserve

Go to the shores of the Koocanusa Reservoir between Fernie and the U.S. border, and you’ll find the only Palouse Prairie ecosystem in Canada, a unique habitat caught between two mountain ranges.

The very dry and very hot forests and grasslands are the only place in the country you can find the endangered Spalding's campion, a long-lived flowering herb.

The Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi'it First Nation regularly monitors for the rare flowering plant on its lands. Members are also working to control invasive plants and are removing cattle from their reserve this year to provide respite.

But the biodiversity hot spot still needs help. According to the KBA Secretariat, that could take the form of managing invasive plants and cattle grazing on provincial lands.

Another big concern is the encroachment of forests onto the grasslands, the result of decades of fire suppression.

Explore all of Canada's Key Biodiversity Areas in this interactive map.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated that in the Fraser estuary, more than 100 species of birds face less than a 50 per cent change of survival over the long-term. In fact, the number of organisms in the region facing a local risk of extinction includes 102 species of birds, fish, bats and marine mammals.