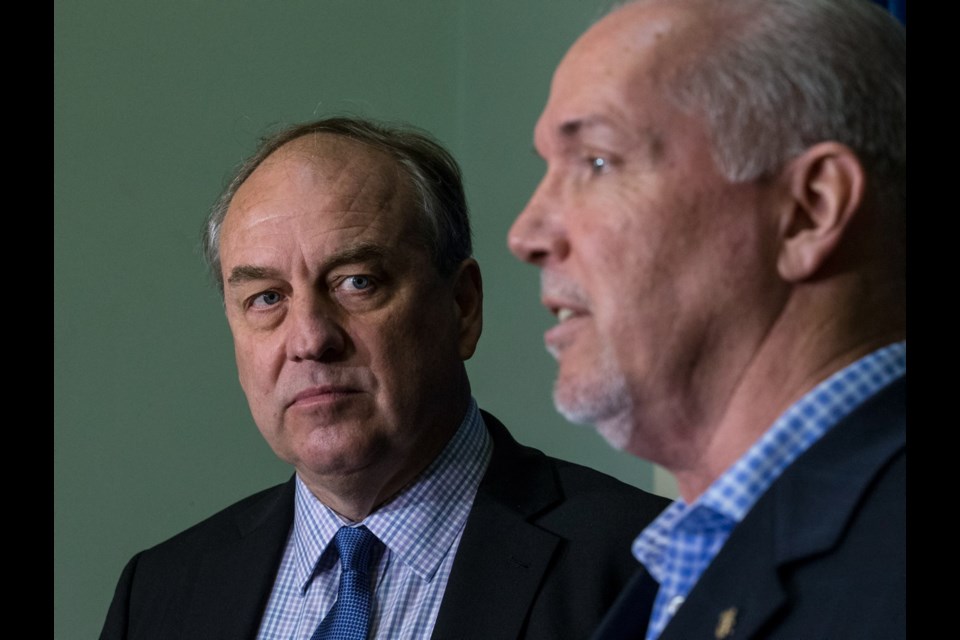

After two and a half years in power, B.C.’s minority New Democrat government enters 2020 under a new cloud of uncertainty. The departure of B.C. Green Party Leader Andrew Weaver could destabilize a power-sharing deal that’s allowed Premier John Horgan to govern in relative security since July 18, 2017.

In the short term, the NDP-Green deal still stands. Green MLA Adam Olsen is the party’s interim leader, and he’s pledged his six-month tenure will ensure ongoing support for the NDP.

But much depends on who wins the permanent job this summer, and whether that person decides to continue the confidence and supply agreement signed between the three Green MLAs and the Horgan government.

“Andrew’s leaving and he’s the signatory to the agreement,” Horgan said. “We don’t know what will emerge from the Green caucus. So I tell my colleagues: ‘Work today like it’s your last day.’ ”

Just as much unsteadiness is emanating from within the NDP itself, as strategists debate the merits of a snap election when opponents are at their weakest, Horgan’s popularity is at its height and the economy is still strong.

“I think with minority governments, any time we could go [to an election],” said Bob Dewar, the NDP’s 2017 campaign director and special adviser to the premier. “Especially 28 months into it, which is much longer than an average minority government.

“We have an agreement that says we’ll be here four and a half years. So if all things were equal, I think that might happen. But I’m not sure how equal they are anymore, with Andrew saying he’s not going to run again and the fact he’s stepping down as leader.”

Officially, the premier says he’s not enthusiastic about an early trip to the polls.

“No one wants an election except the hyper-partisans,” he said. “But regular people are happy. The books are balanced. Services are being delivered. Medical Services Plan premiums are gone. People are happy about a lot of things. So why would I disrupt that?”

Unofficially, his party, like the Liberals and Greens, is planning for just that scenario in mid-to-late 2020.

The case for an election

Some NDP strategists can boil the merits of an election down to one simple point: better to go now, before things get worse.

Horgan’s approval rating of 51 per cent is as high as it has ever been, making the premier a popular asset, rather than a scandal-plagued liability, on the campaign trail.

A snap election would see the NDP able to tout the benefits of a strong economy, prudent spending and several balanced budgets. With darkening economic forecasts, a collapsing forestry sector and a shrinking $148-million budgetary surplus, the economy might not be a positive talking point for the NDP much longer.

A lack of money could also limit the government’s agenda for the final two years in office, disappointing its allies as it limps into the scheduled election date of October 2021 on the back half of a mandate that required spending cuts rather than fulfilling its ambitious promises for social spending.

Even worse, the provincial treasury could tilt into deficit over issues like the Insurance Corp. of B.C., despite an internal scramble from Finance Minister Carole James to cut discretionary spending. That would open the NDP up to attacks that it chronically mismanages B.C.’s finances.

“The financial situation for the B.C. government is deteriorating rapidly, and that’s going to come back to bite the NDP,” said Opposition Liberal Leader Andrew Wilkinson.

“So there are lots of reasons for a spring election.”

The Liberals recently opened the nomination process for candidates in 11 ridings, and a new batch is expected in early 2020. Party volunteers are spending Saturdays knocking on doors, and the Liberals tout an already-vetted list of candidates with 350 credible names to be matched with ridings.

The NDP, meanwhile, has been out-fundraising the other parties, under a law it created that bans corporate and union donations. New Democrats have the financial advantage over a Liberal party still heavily in debt from the 2017 campaign, and a Green party more focused on an internal leadership race than a provincewide campaign.

The Green instability factor

Candidates for the Green leadership have until April 15 to declare. Rules include three public debates, $16,000 in fees to the party and campaign spending limits of $300,000. The winner will be named at a convention in Nanaimo on June 28.

Weaver intends to remain an MLA, despite resigning as leader. That means the three Green signatories to the NDP confidence agreement will continue to side with government to give it a 44 to 42 vote advantage over the Liberals in the house.

If Cowichan Valley Green MLA Sonia Furstenau wins the permanent position, she too would be bound by the confidence and supply agreement. In that scenario, the NDP could coast to the next scheduled provincial election in October 2021.

But if anyone other than Furstenau wins the Green leadership, they would not be required to continue to prop up the NDP.

“In theory, a new leader would not be bound by [the agreement],” Weaver said. “But I don’t see a new leader coming in and wanting to blow everything up. Why would they do that? So I could see the new leader wanting to work within [it].”

There could also be other complications.

If the victor of the Green leadership race is not Furstenau, and therefore not already an MLA, Weaver said he may choose to resign his seat in Oak Bay-Gordon Head so that the new leader could run in a byelection to try for their own seat in the house.

“Let’s suppose that somebody emerges from Prince George, and they win leadership of the party, and then obviously they’ll come knocking on the door and say look, you know, I would like to be in the legislature to build presence, and that’s a conversation I’m open to because that’s the honourable thing to do,” Weaver said.

“When new leaders come in, the honourable thing to do is if that new leader is not already MLA is to step aside and let them.”

However, winning Oak Bay-Gordon Head would not be a cakewalk for Weaver’s Green replacement.

Weaver upset a Liberal cabinet minister to win in 2013 and become the first Green MLA in B.C. history. His personality and work ethic appears to have carried the riding since then. But it remains one of the most affluent in the province, and has strong Social Credit and B.C. Liberal roots.

Were the Liberals able to win it back in a byelection sparked by a new Green leader, that would deadlock the legislature in a 43-vote tie and almost certainly trigger a provincial election.

That scenario has crossed the mind of NDP strategist Dewar.

“If it’s just three [Green MLAs], that’s fine. But if it goes down to two, that means somebody has left and it’s a hung parliament,” Dewar said.

“This is Oak Bay-Gordon Head and yes, Andrew won it in 2013 and 2017, and we won it in a byelection back in the 1990s and one other time, but every other time than that it has been Liberal or Socred.”

The byelection scenario is one of the reasons the NDP remain on high-alert election readiness.

Weaver said he knows the NDP is calculating how to take advantage of the instability.

“Bob Dewar is a brilliant political strategist, without any doubt, so I’m sure he’s worked through every possible pathway and narrative,” Weaver said.

“If I were Bob, and I’m a strategist for a party and I saw this leadership change, I’d be working out all sorts of different potential trajectories. I’m sure he has.”

How an election would — or more likely, wouldn’t — work

There are several ways the NDP could force an election, if the Green instability fails to trigger one organically. But each method is fraught with political risk and potential voter backlash.

The easiest way would be to slip a poison-pill policy into an upcoming budget, throne speech or key piece of legislation the government designates as a matter of confidence — perhaps something like a renters’ rebate (which the NDP campaigned on but the Greens have blocked).

Whatever the issue, the NDP could select something deliberately designed to force the Greens to vote the government down, but also popular enough to serve as the launching pad for the NDP’s election campaign platform.

Given the two parties work closely together, with top cabinet ministers and Greens meeting to consult on priority items on a weekly basis, such a move by the NDP would be tantamount to a sneak attack.

Another scenario could see Horgan simply walk into Government House and ask Lt.-Gov. Janet Austin to dissolve parliament and call an election. By convention, the viceregal representative of the Queen is supposed to listen to the advice of her first minister unless it would harm the democratic interests of the province.

One complication, though, is the fact that the confidence and supply agreement with the Greens also binds the NDP. “The leader of the New Democrats will not request a dissolution of the legislature during the term of this agreement, except following the defeat of a motion of confidence,” reads the document signed by Horgan and each of his NDP MLAs.

A second complication is B.C.’s fixed election date law.

“The LG is bound by convention to act on the advice of the premier to call an early election,” said Andrew Heard, a political-science professor who specializes in constitutional issues at Simon Fraser University.

“That’s not to say the premier is free to call an early election whenever he likes. The spirit of the fixed election date legislation is that fairness for all parties requires set election dates. The possibility of an early election was really thought to be available only following a loss of confidence or a some really extraordinary circumstances that justified going to the electorate.

“In my view a convention has been established that the fixed election dates be respected, but it is of a type of convention that occasional breaches don’t undermine the general rule. I think the principle of fair elections would be seriously undermined if premiers felt they could simply disregard the need to wait four years.”

It’s not an opinion the premier seems to share.

“I could call an election tomorrow,” Horgan said. “That’s my prerogative as premier. But it’s not my intention to do that.”

Horgan has also spent much of his first two years in power boasting how his minority government is accomplishing its agenda and working well with its Green partners. To trigger an early election would be an abrupt and dramatic reversal of his entire message.

“With everything staying the same as it is right now, I don’t think we could engineer an election,” Dewar said. “I think it’d be very difficult to do. I have seen, in the past, governments engineer elections when the time wasn’t ready.”

The 1975 NDP government of Dave Barrett attempted a similar manoeuvre, triggering an early election that year. An angry electorate refused to return the party to power. A book on the Barrett government successes and mistakes was later written by veteran journalist Rod Mickleburgh and NDP strategist Geoff Meggs — the latter of whom is now Horgan’s chief of staff and top political adviser.

The NDP minority government is now 28 months into its tenure — longer than the Canadian average for a minority of government of around two years. It could sail the full four and a half year term, or end in a matter of months, depending on the events of early 2020.

“We need to be prepared at all times,” Horgan said.

“I’ve taken every day as it comes. And that I think is the strength of our government. What are the circumstances that are in front of me, how do we as a group deal with those, always mindful that it’s about people? And if we keep focusing on the services that we want to deliver, the calibre of policy changes and what they mean for communities, I think we’ll be fine. Because if we’re on the right foot, in all of these situations, the public will say carry on.”