Victoria-based author Moira Dann has always been fascinated by Confederation-era social history. As the current president of Craigdarroch Castle Museum Society’s board, she has become intimately familiar with the many objects Victoria’s bonanza castle has to offer visiting guests. Although today’s visitors are relegated to booking a time in advance and all tours are self-guided due to COVID-19 restrictions, Dann and others are eagerly waiting to return in droves, squeezing past unknown attendees to get a glimpse of something glamorous from a bygone era.

In Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures (available April 20), Dann whisks readers through the many rooms of Robert and Joan Dunsmuir’s Castle — no elbowing necessary — regaling readers with the bounty of treasures collected over the decades, including stained-glass windows, an ancient intercom system and pianos, like the ones mentioned here.

Some might say it’s preposterous to think an overview of a massive story repository such as Craigdarroch Castle can be reduced to not even two dozen objects. …

Why twenty-one objects? The number may seem a bit arbitrary, but it comes from the desire to vary the story of the castle’s nineteenth-century beginnings and carry it forward to the current century for contemporary readers and for future generations, with each object used as a hook on which to hang a story and offer some context and tangential information.

Craigdarroch Castle houses more than just the stories of the shipping, railway, and coal baron (and western Canada’s richest man, for a time) Robert Dunsmuir, his wife, Joan, and the fractious, fractured family he left behind. It also cradles the stories of the maimed and shell-shocked men sent home by the Empire after the Great War and cared for from 1919 to 1921 at Craigdarroch Military Hospital, as well as those of Victoria College, the Victoria Conservatory of Music, the Victoria school board, and the efforts of the Craigdarroch Castle Historical Museum Society.

It is a collection that allows us a peek into the lives of different people in a different time and provides us a bit of context for our lives in the twenty-first century. The objects range from world-class stained glass to tatting shuttles to a young officer’s sabretache and spurs that speak of the military expectations of young men in the early twentieth century. Tales of class distinction are revealed through the examination of radiator brushes used by servants and the story of a piano ordered by one Dunsmuir brother and ultimately delivered to another brother in another city.

It is a collection that allows us a peek into the lives of different people in a different time and provides us a bit of context for our lives in the twenty-first century. The objects range from world-class stained glass to tatting shuttles to a young officer’s sabretache and spurs that speak of the military expectations of young men in the early twentieth century. Tales of class distinction are revealed through the examination of radiator brushes used by servants and the story of a piano ordered by one Dunsmuir brother and ultimately delivered to another brother in another city.

These objects can set our imaginations alight. Imagining an earlier time helps us create a better now and imagine a better future.

FROM CLASSIC STEINWAY TO MELODEON: CRAIGDARROCH KEYBOARDS

Music was often heard at Craigdarroch Castle. The Dunsmuir family enjoyed listening to it as well as making it. It was a feature when they entertained in the drawing room or just spent time there together as a family, and certainly when they hosted big events in the dance hall on the top floor.

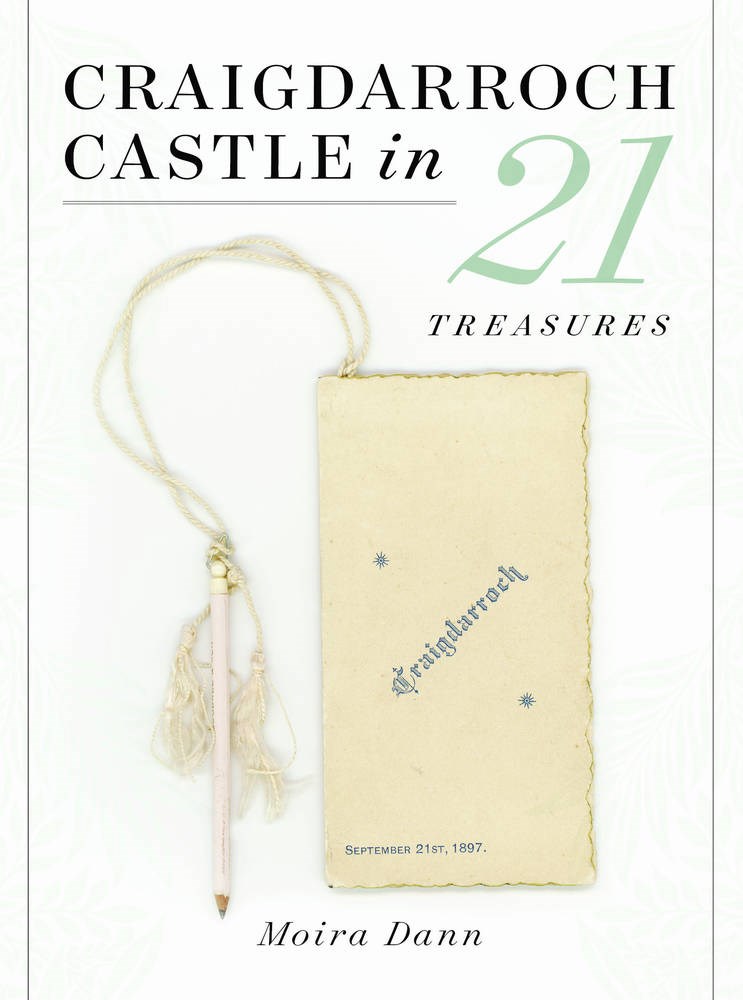

Those events—such as the evening in 1894 when it’s said 110 Victorians danced, and for which there is a gold-coloured dance card with its own golden pencil —were among the few socially sanctioned places where young men and women could gather to meet, dance, and “court,” with an eye toward matrimony. There were also elaborate events held when some of the Dunsmuir daughters came out and made their debut and were officially presented to society.

There are three pianos (among four keyboard instruments) in Craigdarroch Castle. Each has a story, but the jewel in the crown is the Steinway grand piano in the drawing room. Known as an “art case” Steinway, the instrument has enjoyed regular, if not continuous, use over the last century. The term refers to the elaborate designs that make the piano unique. The Dunsmuir art case features floral swags and depictions of musical instruments and notation along with bouquets.

This piano ended up with a different member of the Dunsmuir family from the one who commissioned it from the Steinway factory in New York City in 1898. It was Robert and Joan’s younger son, Alexander Dunsmuir, who made the purchase for the grand California home he was building. When he bought it, he was in New York with the woman he called his wife but had yet to marry, to visit his stepdaughter, the actress Edna Hopper. But it wasn’t long before Alexander’s life was taken by the alcoholism that had long undermined his health. He died on January 31, 1900, in New York City on his honeymoon, and his wife, Josephine, died of cancer soon after.

His estate went in its entirety to his brother, James, so the piano was shipped to Victoria via Toronto from the Steinway facility in New York. It was a centrepiece at Burleith, the home of James and Laura Dunsmuir, and then it moved with them to Government House when James became lieutenant-governor in 1906. It later accompanied them to Hatley Castle when the family moved there in 1910. The greatest beneficiary of the instrument was Elinor Dunsmuir, the fifth-eldest daughter and seventh of James and Laura’s surviving twelve children.

Elinor (or Elk, as she was known in the family) was a big talent and very smart, but the social constraints on women of the day didn’t permit her to be part of the business or to do much else other than seek a good marriage. It’s believed Elinor was gay, so the marry-well-and-have-heirs route didn’t suit her. Her musical talent offered her a way out—talent she expressed on this piano. She spent much of her adulthood in Europe, studying and composing music for the stage and the ballet, and worked alongside greats such as Noël Coward. She also had a taste for gambling and did a lot of it in Monte Carlo.

The piano was used in performance of and to record some of Elinor’s music in 2018, for a recording titled “La Riche Canadienne” (as Elinor was known in Monte Carlo).

The piano was auctioned off for $500 in 1939 after Laura Dunsmuir died. James and Laura’s daughter, Muriel Dunsmuir, bought it back in 1953. It changed hands several more times before finding its forever home at the castle in 1985.

In many ways, even more remarkable than the New York–crafted Steinway in the drawing room is the upright piano in the third-floor billiard room. Its pedigree is strictly local, with its metal frame having been cast at Albion Iron Works, partly owned by the Dunsmuir patriarch, Robert, and situated on Government Street. The piano builders were Charles Goodwin and G.W. Jordan, whose firm had a short life; they were thought to have crafted only thirteen pianos. This Goodwin and Jordan piano is believed to be one of very few still extant. It came to Craigdarroch in the late 1800s.

Its other claim to fame is its ownership by Martha Harris, daughter of Sir James and Lady Amelia Douglas. Mrs. Harris left behind the vibrant correspondence she had with her father when she was in school in England. Later, after her parents died, she wrote a book, in which she shared the stories her Métis mother had told her when Harris was a youngster.

The third piano is the Collard & Collard in the fourth-floor dance hall that visitors are welcome to play.

Another keyboard worth noting is the melodeon in the dance hall. It came to Victoria from California in 1875, brought by Theophilus Elford, who established the Shawnigan Lake Lumber Company. The instrument was his wedding gift to his bride, Lillie Louisa Robertson, with whom he had six children. Lillie died in the Point Ellice Bridge collapse with their daughter, Grace Constance. The bridge collapsed on May 26, 1896, when a streetcar carrying 143 passengers on their way to celebrations of Queen Victoria’s birthday fell into the Gorge Waterway. Fifty-five people died. An investigation found both the Consolidated Electric Railway Company and the Victoria City Council responsible for the accident, as the bridge was not constructed to handle the heavy weight of a streetcar and inspection techniques undermined the structure.

A melodeon is a type of reed organ that was popular in the latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. A key-board wind instrument, it makes sound by drawing air (its suction created by a foot-pump bellows) over reeds. It’s the suction that makes it different from a harmonium, which pumps air through reeds to make sound.

The book launch for Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures on Thursday, April 22, will be hosted, virtually, by Craigdarroch Castle. Visit www.thecastle.ca for more info.

Excerpted with permission from Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures by Moira Dann 2021, TouchWood Editions. Copyright © 2021 Moira Dann.