Deep beneath the ocean’s surface off the west coast of Vancouver Island lies a mountain range of about 50 underwater volcanoes — measuring from 1,000 to 3,000 metres high.

These seamounts, as they’re more accurately named, are here for the same reasons there are earthquakes and tsunamis along British Columbia’s coast, says Cherisse Du Preez, head of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s deep-sea ecology program.

“We have tectonic activity that is very active and very close to shore,” she said. “It’s like the Rocky Mountains down there.”

On June 16, Du Preez and a team of researchers embarked on an ambitious three-week deep-sea expedition to study and monitor these ecosystems.

The collaborative expedition involving DFO, the Council of the Haida Nation, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council and Oceans Network Canada will provide baseline data for scientific monitoring and research for a number of existing and planned Marine Protected Areas.

“We are going to habitats that nobody’s mapped before, that nobody’s seen before — and we’re seeing animals that science didn’t know existed,” said Du Preez, the lead scientist on board for deep-sea ecology.

About 75 per cent of Canada’s seamounts are contained within the expedition’s study sites, which extend from 200 kilometres west off the northern tip of Haida Gwaii to the southern edge of Vancouver Island — an area roughly four and a half times the size of Vancouver Island.

When you’re approaching the seamounts by boat, Du Preez said, whale sightings become more frequent and seabirds more abundant.

The research vessel’s echo sounder — which calculates the water’s depth — will start pinging shallower and shallower, she said. Suddenly, it will jump from reading three-and-a-half kilometres deep to just a couple hundred metres deep.

“And you realize that this mountain has just risen up underneath you and you’re sitting at the top of it,” she said. “And the reason why there’s animals everywhere is because there’s so much life on this mountain that would otherwise be just like a desert of water.”

Seamounts provide habitat for animals that usually have to compete with humans for resources, Du Preez said.

“Out there, there’s just this island oasis where they get to exist away from us,” she said. “We find corals and sponges and fish and sharks and octopus all living on the seamounts.”

Outside of this region, seamounts are most commonly found in the high seas, which Du Preez described as “the wild, wild west.”

But because these seamounts are within Canadian waters, Du Preez said this multi-nation and federal government partnership has the power to protect them.

“If you’re going to protect a place in the ocean, why not protect where everything comes to feed or to nurture their young?”

Like a ‘fire hose’ blasting from the earth

What makes the study sites even more rare is that they contain 100 per cent of Canada’s hydrothermal vents.

Typically, water at the bottom of the ocean is around 3 C, but Du Preez said hydrothermal vents gush out water that can be up to 400 C.

“This geothermal-heated water blasts out of the earth like a fire hose all of the time,” she said. “It’s not your average seawater. It’s like super-enriched seawater.”

A whole host of animals depend on these hot springs, which are highly rich and only exist within hydrothermal vents, Du Preez said.

These chemosynthetic animals live in the absence of sunlight and depend on the chemicals produced by hydrothermal vents for food.

“It’s like a slightly alien world that we didn’t know existed because we thought everything on the planet required sunlight,” she said. “It’s this incredible, weird place where life can’t exist unless you’re these specialized life forms.”

Hydrothermal vents were only discovered 30 years ago, and the first seamount was identified around 90 years ago, said Du Preez.

“We know more about the surface of the moon than we do the deep sea,” she said. “We joke in deep-sea science that it’s not rocket science — it’s harder.”

130 countries tune in

A team of around 15 experts with diverse backgrounds — including two representatives from Haida Nation – has been tasked with exploring, documenting and providing science-based solutions on how to best manage and monitor these environments.

Irine Polyzogopoulos, Uu-a-thluk communications and development co-ordinator, said a Nuu-chah-nulth representative is not onboard this year’s expedition, but they hope to have someone onboard next year.

“The timing just wasn’t right,” she said.

But Polyzogopoulos said they will be conducting student and public “ship to shore” virtual outreach events, as well as sharing information through social-media channels to keep people connected to the work taking place at sea.

The public can tune into these events online and virtually ask questions to crew members in real-time, Polyzogopoulos said.

Joshua Watts was a Nuu-chah-nulth representative aboard the 2019 deep-sea expedition. At the time, he was studying ocean and atmospheric science at the University of Victoria, so the experience “fit perfectly,” he said.

Including a Nuu-chah-nulth worldview as part of the conversation is “invaluable,” said Watts.

“Responsible decision-making is at the forefront of our minds,” he said. “We’re thinking 10 generations down the line. How are our decisions going to affect our descendants?”

When Watts thinks about the different species found within the deep sea, he said the Nuu-chah-nulth way of teaching comes to mind.

“It’s always been through experiential learning,” he said. “Through first-hand knowledge.”

Because of that, Watts said a major part of his role involved sharing what he had learned on the expedition with his community and the younger generation.

“My experiences can only go so far, but if I share them they reach other people,” he said. “And I think it has a lot more impact.”

Du Preez said a major objective of the expedition is to resolve how important these “very localized spots of increased diversity and biomass” are for the overall health of the ocean.

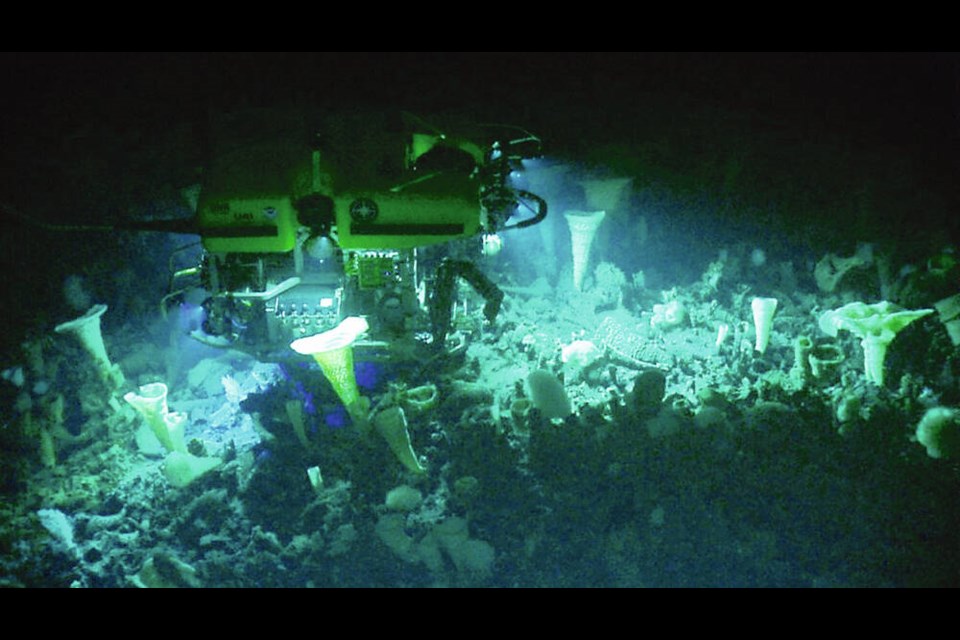

To do this, they’re relying on a submersible — a robot the size of a small car with cameras, sensors and arms — that will be sent about three kilometres deep into the ocean to explore and collect samples.

Onboard the ship, the team of experts maneuvers the robot from a control room while live-streaming the footage globally.

During past expeditions, Du Preez said, up to 130 countries were tuned into the live-stream at the same time.

Through live-chats, researchers and scientists from across the world can help identify which animals have never been seen before, Du Preez said.

“We rely on that connectivity with the world because we need people to be watching in real-time to help us,” she said. “This is an investment in global biodiversity.”

Feds take sole jurisdiction

The expedition is endorsed by the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, and funded by DFO, with resource support from Ocean Networks Canada.

Although they were only recently discovered, these deep-sea environments are already being affected by climate change, Du Preez said.

In the last 60 years, the ocean has lost 15 per cent of its oxygen, she said.

“And because these animals are so fixed in space [with] where they can exist, they don’t have the option of migrating as easily as other animals,” Du Preez said.

Sometimes, Du Preez said, it feels as if she’s just watching the decline of these ecosystems.

“But then I remember that if we have a Marine Protected Area, we can mitigate,” she said. “We can stop everything in our control.”

The federal government is committed to conserving 25 per cent of Canada’s land and oceans by 2025 and continues to advocate internationally to protect 30 per cent of the world’s ocean by 2030, according to DFO.

One of the expedition’s study sites includes a large offshore block west of Vancouver Island that was identified as an area of interest in 2017, opening up the process of designating the region a Marine Protected Area, entitled Tang.ɢwan-ḥačxʷiqak-Tsig̱is.

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Judith Sayers said this was decided without any input from the First Nations whose territories fall within the proposed Marine Protected Area, including the tribal council and Haida Nation, as well as Quatsino and Pacheedaht First Nations.

“We have told [DFO] from the very beginning that if they want to have this Marine Protected Area, we have to have co-management of [it],” Sayers said. “This [MPA] is within our territories and we really need to be able to protect them.”

Conversations between the nations and DFO have been ongoing since 2018, Sayers said.

“We’re trying to define collaborative governance and management,” she said.

According to Sayers, DFO argues that because the proposed Marine Protected Area is within an international economic zone, “it has to be the sole jurisdiction of the federal government.”

A statement from DFO said that it is “committed to working with partners to provide the best science available, achieving domestic and international biodiversity conservation targets through co-management and science-based decision-making.”

Limiting marine traffic to reduce noise pollution and potential oil spills, along with limiting fishing, is one way to “give these environments the best opportunity to survive that we can,” said Du Preez.

While they help, Du Preez was careful to note that Marine Protected Areas don’t “solve everything.”

“Despite our best efforts, despite everything we’re trying to control, climate change is still going to take away this biodiversity in the ocean,” she said. “If we’re not going to do something on a larger scale about climate change, this is what we have to be willing to lose.”