I followed Emily Carr into the wilds of Haida Gwaii.

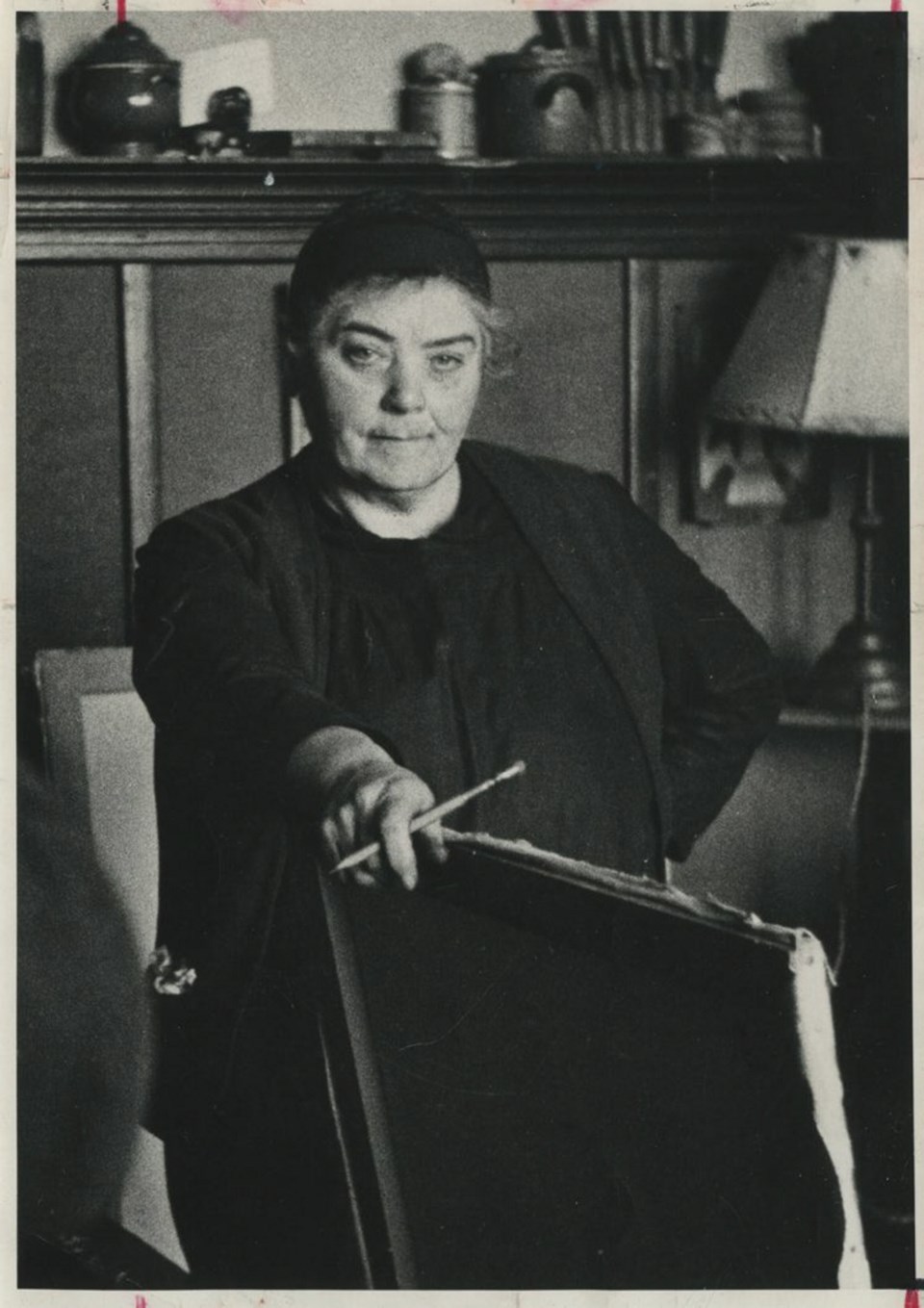

To prepare for a sailing trip aboard the Maple Leaf schooner in 2004, I visited her paintings in the Victoria and Vancouver art galleries, marvelling at the lightness of her sea and sky paintings, her dark, brooding forests, the powerful portraits of ravens, eagles and totem poles.

In early May, my friend and I drove up Vancouver Island to Port Hardy and boarded an early-morning ferry that, by nightfall, would take us north 274 kilometres to Prince Rupert. A second, overnight ferry would take us to Skidegate a few days later.

I thought of Emily Carr chugging across Hecate Strait in a small boat driven by a First Nations couple, Jimmie and his wife, Louisa. I imagined Carr, dressed in long skirts, petticoats and a corset, jumping in and out of boats and canoes, struggling through salal to explore the villages of Tanu, Skedans and Cumshewa.

In the warmth of the Maple Leaf’s galley, the night before we went ashore on Tanu, we read aloud from Klee Wyck, Carr’s first book, which won the Governor General’s Award in 1941. Carr captured her arrival at the abandoned Haida village perfectly, an experience that our own would mirror.

“It was so still and solemn on the beach, it would have seemed irreverent to speak aloud; it was as if everything were waiting and holding its breath. The dog felt it too; he stood with cocked ears, trembling,” she wrote.

It’s hard to imagine that this writer, this painter, was born in an Italianate-style villa with an English garden in James Bay.

But Carr burst out of this manicured environment into nature. She was often seen pushing a pram through Beacon Hill Park with her monkey, Woo, and her dogs, admiring the pine trees and the broom, the fawn lilies and the blue camas.

Carr died 75 years ago, on March 3, 1945, at St. Mary’s Priory, a convalescent nursing home that is now the James Bay Inn. She has left a powerful legacy and continues to inspire artists, poets and environmentalist.

Carr attended the best art schools in San Francisco, London and Paris, but soon realized she was not a traditionalist.

“I drew away from the old-school methods of teaching, realizing the cramped style of London and Paris could not adequately describe Canada,” she said at the time.

Jan Ross, the former curator of the Emily Carr House at 207 Government St., said Carr remains relevant because she was on the same spiritual quest as many people are today.

She wasn’t religious, but she was a very spiritual person, said Ross. She talked about “the tabernacle in the woods,” and said “the woods are my cathedral.” She would just go off into the forest knowing there were wolves, cougars and bears.

“It took an incredible amount of physical courage, but she didn’t see it that way. It was her connection to God. That’s something that’s really strong in her journals. Her painting, and particularly going out into the forest, was her spiritual path to the Creator,” said Ross.

Carr was also an environmentalist long before the term came into use. She painted stumps and clearcuts and spindly pine trees struggling to reach the sky.

“There’s a torn and splintered ridge across the stumps I call the ‘screamers,’ ” Carr wrote in 1935. “These are the unsawn last bits, the cry of the tree’s heart, wrenching and tearing apart just before she gives that sway and the dreadful groan of falling, that dreadful pause while her executioners step back with their saws and axes resting and watch. It’s a horrible sight to see a tree felled, even now, though the stumps are grey and rotting.”

Carr was worried about forestry practices even then, said Ross.

And she moved among Indigenous people for years. Ross knows of four First Nations artists who have been inspired by and have their own artistic relationship with Carr, including poet laureate Janet Rogers, Witness Blanket installation creator Carey Newman and artists Sonny Assu and Hjalmer Wenstob. “We call it Emily Carr’s legacy of inspiration,” said Ross.

“That’s what she leaves with you. And we see it all the time, people coming to the house, people coming to British Columbia and Vancouver Island and it’s not just Victoria. They are on a path, a pilgrimage to see where Emily lived and painted.”

Over the course of a summer, hundreds of people come specifically to Victoria because they’ve read her books or read about her, said Ross. They’ve seen her work and they’ve seen films inspired by her.

American author Susan Vreeland wrote a book about Carr called The Forest Lover that has brought many American visitors to Victoria, mostly women who are in book clubs, said Ross. “And they are coming to B.C. and specifically Vancouver Island and they are starting with her birth house and are going to the places Emily painted. They’re going to Haida Gwaii.”

Ross heard her favourite story about Carr’s influence from a pedicab driver who picked up two well-dressed African women in front of the Empress Hotel several years ago. They were in their early 80s and they had come to Victoria to stay at the Empress because of Carr, said Ross.

When they said they wanted to go to Emily Carr’s house, the pedicab driver started to tell them about the famous artist. But they interrupted him and they told him all about Carr, said Ross.

“They discovered her when they were little, little girls. They went to a mission school and they were given Emily Carr’s books to learn how to read. They became very successful because no one in their village knew how to read and write. These two women helped their families, their village, themselves. They became very successful businesswomen because they learned how to read. The books the missionary had were Emily Carr’s Book of Small and Klee Wyck,” said Ross. “The story still gives me chills.”

Carr’s writing speaks to a lot of people, said Ross. Some people say they aren’t really fond of her art but they love her writing. “Then they come to B.C. and they understand it. People complain that her paintings are so dark, but they go into our rain forests and they say: ‘Oh, I get it,’ ” said Ross.

In Carr’s birthplace, there is a shelf of poetry books that have been inspired by her.

“She still does inspire,” said Ross. “It’s her art. It’s her writing. It’s how she lived her life. It’s her fierce independence. These are things that ring true to people.

At the end of her life, when Carr could not get into the forest because of ill health, she would walk to Dallas Road. It’s where she painted a whole series of her sea and sky paintings.

“You can go to those exact spots and see what she saw. That’s my favourite place where she painted,” said Ross.

“You see them. And then you walk that same path and you go: ‘Oh I’m looking at those Olympics and they are that colour. You’re right, Emily.’ ”

Carr’s sea and sky paintings have been compared with the impressionist paintings of Vincent Van Gogh. They’re light and bright and completely different from her dark forest paintings, said Ross.

At times, her life was a struggle. But when you read the journals from the very end of her life, she appears to feel satisfied in many ways, because her goal was not to sell her paintings. Her goal was for people to understand her paintings, said Ross.

“They do start to sell and certainly she can use the money. But more than anything, she feels she is achieving that goal here of getting close to the Creator. Her life’s work was bringing her closer to the Creator. How wonderful. I kind of feel some hope,” said Ross.

“I think that’s why people today — men, women, all ages — this is what draws them to her and her art.”

Carr was also very loved by her sisters and by a close circle of friends.

At her final resting place, close to the sea and beneath the skies she painted, admirers have left feathers, money, paint brushes, paintings and poems.

Carr’s grave is the most visited in Ross Bay. This is where people make another form of pilgrimage “leaving little talismans for Emily,” Ross said.