Fairy Creek protester Forest was 17 when she was arrested at Clayoquot Sound in 1993.

During a trip to Long Beach, near the shores of the sound, she saw firsthand the effects of clearcut logging in the area. (While her employer gave her its blessing to take time off to join the effort, Forest — like many others — uses an alias because participating in the Fairy Creek protests may compromise her livelihood.)

Forest decided then that she was going to be a part of the War in the Woods, as the mass protests against logging in the Clayoquot Sound area were dubbed.

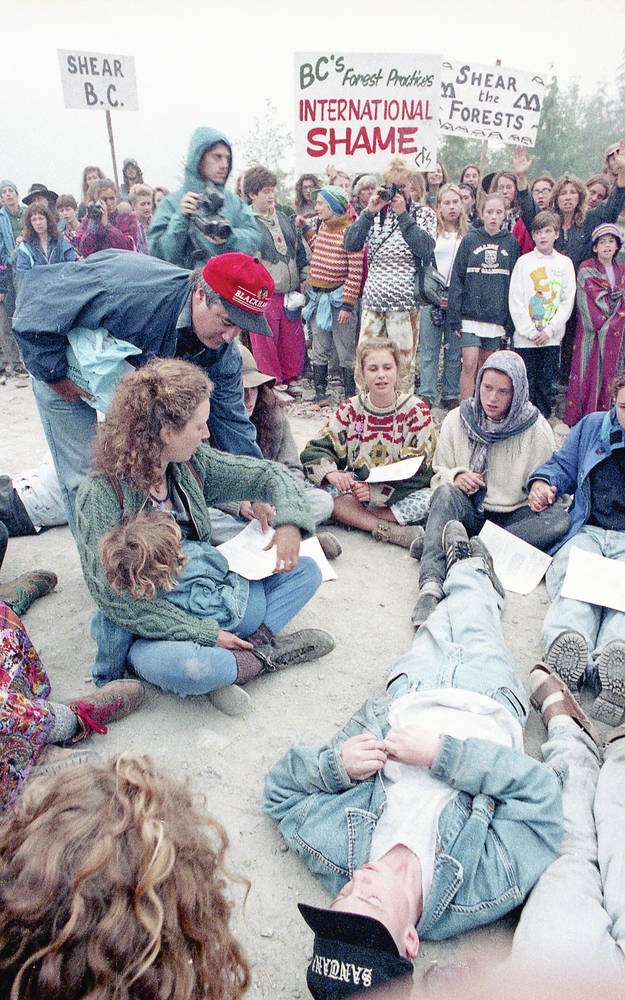

For three months, she participated in the protests, doing anything she could do to help the movement until the day she was arrested. She was one of 856 people arrested in the internationally covered six-month uprising before the campaign ended in October of 1993.

Like those who would follow them in recent months at Fairy Creek near Port Renfrew, Forest and the other Clayoquot protesters often found themselves cold and wet, soaked by near daily rainfall. They would get up early, between 4 and 5 a.m., and head down the road to Kennedy Bridge, where most loggers had to pass to access the pristine old-growth forests of Clayoquot Sound.

At Fairy Creek, as at Clayoquot, there’s a kitchen that feeds protesters three meals a day, workshops are available to newcomers on topics ranging from being arrested to forest education, and a dedicated core of mostly young people takes charge of the daily operations and organization of the camps.

There are other similarities between the two campaigns. For both 1993’s War in the Woods and 2021’s Fairy Creek protests against old-growth logging, an NDP government was in power in B.C. and Canada was recovering from a global recession.

But there are stark differences, too. This time around, far more attention in the protest camps is being paid to the role of Indigenous people. And many protesters who were involved in both efforts say the relationship with police was friendlier at Clayoquot, that the daily arrests were more of a ritual where everyone played their part.

While there was intensity to the Clayoquot protests, at Fairy Creek there is something closer to a desperate urgency, said Tzeporah Berman, a lead organizer and prominent voice of the protesters during 1993’s War in the Woods.

“Every minute matters,” said Berman, who was arrested at both Clayoquot Sound and Fairy Creek.

In the era of the Clayoquot protests, there was much more old-growth forest left in B.C. compared to today, she said. Studies now suggest there is as little as three per cent of old-growth forest left in the province.

Alison Acker of Victoria spent three weeks in jail for blocking loggers’ entry across Kennedy Bridge at Clayoquot Sound. Now 92 and equipped with a walker, she has visited the Fairy Creek protests several times in hopes of being arrested again. The atmosphere, she says, was much more jovial at Clayoquot. “It was very much like a pageant or staged event.”

The RCMP would arrive and spray-paint orange lines on the ground to separate onlookers from the action as they approached the protesters for arrest. Most protesters walked out peacefully alongside officers as they were taken into custody.

Protesters who were there say there was little tension or animosity between the two groups in the daily ritual. For the arrestees, it was about making a statement — they wanted to show the world that their cause was worth being arrested for, that the forests of Clayoquot Sound should be saved.

However, there were some protesters who chose to “hard block” the RCMP, refusing to move and forcing the police to carry them off. At Clayoquot, this often took the form of acting like a “limp noodle,” said Forest.

“I don’t know anybody who had a bad time with the RCMP [at Clayoquot],” said Acker. “There was no fear.”

“They were sweet as pie with me,” Forest said of how the RCMP treated her when she was arrested at Clayoquot Sound.

The night before Forest’s arrest, there was a large windstorm and almost all the protesters fled their encampment for shelter in the nearby town of Ucluelet. Forest stayed behind with a small number of others. During the night, a young logger came to the camp and offered the remaining protesters refuge from the storm — where they kept a low profile to avoid being spotted by the logger’s neighbours.

First thing the next morning, after the storm had passed, she went straight out to Kennedy Bridge. Few people were there because of the storm, so Forest felt the need to fill the gap and put herself forward to be arrested.

“Everybody has a moment where they grow up,” said Forest, who credits her arrest at Clayoquot with helping her develop into the person she is today.

Now, 28 years later, she has taken time off from working in the security sector for industries such as fishing, mining and forestry to participate in the protests.

At Fairy Creek, “hard blocks” are a gruelling fact of everyday life and much more intense. Arrests are daily and protester resistance is gritty. “Out here, it’s a war zone. It’s literally a war zone and [that’s] not an exaggeration,” Forest said.

Protesters lock their arms in the ground in homemade devices called Sleeping Dragons, made of a PVC pipe set in concrete. They sit chained atop metres-high tripods made of three or more logs or trees — sometimes assembled in a hurry when RCMP are unexpectedly spotted — putting their bodies on the line to slow the RCMP’s progress in clearing roads leading to old-growth trees. The contraptions protesters devise can take hours for the RCMP to dismantle safely, since failing to go slowly can cause serious injury.

The goal for the protesters is to hold out as long as possible — they see every extra minute gained as a small victory.

But long extractions can be an overwhelming and stressful ordeal for even the most dedicated to the cause, involving loud and heavy tools such as jackhammers and hand saws and use of a full-on construction-site excavator digging centimetres from them. For some, it’s just too much, and they voluntarily unshackle themselves and walk away with police to avoid an hours-long arduous process.

Berman says there was a casual and friendly nature to the relationship between the protesters and the RCMP at the Clayoquot Sound protest that she hasn’t seen at Fairy Creek. Many officers at Clayoquot were on a first-name basis with Berman, and water-cooler-like conversations were common throughout the day in between periods of action.

By contrast, at Fairy Creek, RCMP are blocking media and supporters of the protesters from accessing the area entirely in what Berman sees as a very heavy-handed approach. “I’ve experienced RCMP exclusion zones [at Fairy Creek] that, in my opinion, threaten the safety of and rights of citizens.”

Yvon Raoul, who was at both protests, said the way journalists have been treated is very different at Fairy Creek. “I feel like journalists have been hampered from doing their job [at Fairy Creek],” Raoul said. “At Clayoquot, it wasn’t like that. It was totally open.”

Journalists were free to go where they wanted at the Clayoquot Sound protests, he said, while at Fairy Creek, police have made it very difficult — requiring media to have an RCMP escort and keeping them well back from protester “extractions.”

In fact, RCMP restrictions on journalists within the injunction zone have prompted a coalition of Canadian media outlets and groups to take the Mounties to court.

Sgt. Chris Manseau, media relations officer for the B.C. RCMP, said he feels the overall relationship the RCMP has built with the media at Fairy Creek has been strong, but safety is the priority when granting access to media.

“I put out a media invite every day. Media are being invited in to film wherever it’s deemed safe,” he said.

Manseau said he couldn’t comment on protesters’ accounts of differences in the relationship between protesters and Mounties at Fairy Creek and Clayoquot Sound, because he was not there when the actions took place 28 years ago — in fact, he was still in high school.

He previously told the Times Colonist, however, that police at the blockades are just doing their job in enforcing the injunction obtained by Surrey-based Teal-Jones Group, the forestry company that owns Tree Farm Licence 46, against those blocking access to logging areas. “Laws are being broken and I’m a police officer, and I have to uphold the laws in Canada because that’s my job.”

Another big difference at Fairy Creek is the involvement of the Indigenous community.

“Nobody ever mentioned the First Nations [at Clayoquot],” said Acker.

As at Clayoquot Sound, the Fairy Creek headquarters, and other camps, hold evening meetings for everyone and encourage newcomers to partake. This time around, however, Indigenous voices are a core focus of the protest movement.

Decolonialization workshops and lectures are held and marches are led by Indigenous youth and elders such as Victor Peter, seen by protesters as the Pacheedaht hereditary chief, and Pacheedaht elder Bill Jones.

It’s important to note that the title of hereditary chief is disputed. Frank Queesto Jones is recognized by the Pacheedaht elected council as hereditary chief. The Pacheedaht band council has also not welcomed the protesters and their actions. The Pacheedaht have released multiple statements since April asking protesters to leave and to respect their authority over their land. Protesters say that they have been invited and given permission to be on the territory by elder Bill Jones.

Newly arrived protesters are greeted at the entrance to the headquarters camp by a checkpoint manned by several protesters. They are asked to read a several-page pamphlet from the protest group Rainforest Flying Squad before entering, explaining the group’s reason for taking action to protect old-growth trees. The pamphlet explains how to create safe spaces for Indigenous people and people of colour, with instructions such as: “explicitly avoid acts of any cultural appropriation” and “avoid tokenizing or fetishizing people of colour or Indigenous people.”

The pamphlet urges newcomers to educate themselves on Indigenous issues by reading the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and reports from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People and the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls inquiry.

At the evening circles, Grandma Losah, an elderly Tla’amin woman, and Indigenous youth teach the mostly white protesters about Indigenous issues within their territories. Protesters are asked not to talk while she speaks. Her meetings commonly end with Indigenous songs, often focusing on the important role of women in their movement and in their cultures.

“I do appreciate all the settler support. It’s something I’ve never seen before,” says Sage, a 23-year-old Nuu-chah-Nulth woman who is part of the protest.

Sage — who asked that her real name not be used because she has already been arrested and been served an order preventing her from returning to the injunction zone — says for her, the protest is about more than just saving old-growth trees. Her great uncle went to the same residential school as elder Bill Jones. So, when she heard the call from Jones and his niece, Kati George-Jim, she came to give them her support.

If the trees are gone, so, too, is the hope of being able to reclaim their culture, their teachings, their language and the ability to reconnect, Sage said.

“It’s so important for us to protect this land because that’s the way we learn. We learn our tradition and our ceremonies on the land with our ancestors — which are these trees,” she said.

Sage’s role is to maintain the sacred fire, create “safe spaces” for Indigenous people and help in the “decolonization” effort through workshops.

The protest camps offer a place for Indigenous youth to learn how to reconnect with their culture, she said. They learn their songs, their language and art forms such as wood carving.

“For all of us, we’re doing this dance of protecting the land so we can continue learning from it, because that’s how our people learn,” Sage said.

Ultimately, the Clayoquot Sound protesters’ actions led in 2000 to the entire sound being designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

This time around, the province has agreed to a two-year deferral on old-growth logging in the Fairy Creek watershed and Central Walbran — affecting about 2,034 hectares of old-growth forest — at the request of the Pacheedaht, Ditidaht and Huu-ay-aht First Nations, who say they want the time to prepare stewardship plans for the areas in their territories. Teal-Jones Group has said it will abide by the nations’ request and put a stop to harvesting and road-building in the deferral areas.

It’s a small win for the protesters, but in their eyes, there is still a long way to go. They want to see all old-growth in the province protected, not just trees in the deferral areas.

“Fairy Creek is the tinder that could relight international controversy in what’s happening in British Columbia’s old-growth,” said Berman. “And that’s what happened last time. Clayoquot was the spark.”

Norman Galimski is a 2021 graduate of the Langara College journalism program.