On June 1, Stan Proboszcz loaded up his kayak and caught the ferry from his home in Powell River to Comox on Vancouver Island. The ensuing two-hour drive would take him past snow-crested peaks and deep forested valleys until he reached a boat launch in Gold River.

Dipping his kayak into the waters of Muchalat Inlet, Proboszcz set out on an 18-kilometre paddle toward the open Pacific Ocean — and he did it all on an anonymous tip.

A tipster had told Proboszcz, a fisheries biologist at Watershed Watch Salmon Society, that salmon farms off the coast had been experiencing mysterious and massive die-offs and nobody was saying anything about it.

“Yeah, it was a little crazy,” said Proboszcz of his decision to make the long trip. “But he didn’t know why they were dying.”

Before Proboszcz left, a colleague had tracked a number of boats that were allegedly bringing fish all the way around the south end of Vancouver Island and into the Nanaimo area. But the boats had nearly finished shuttling all the fish, according to the anonymous source.

Desperate, Proboszcz had tried to hire a skiff and even a helicopter to see what was going on. But nothing worked out, and so he decided to take matters into his own hands.

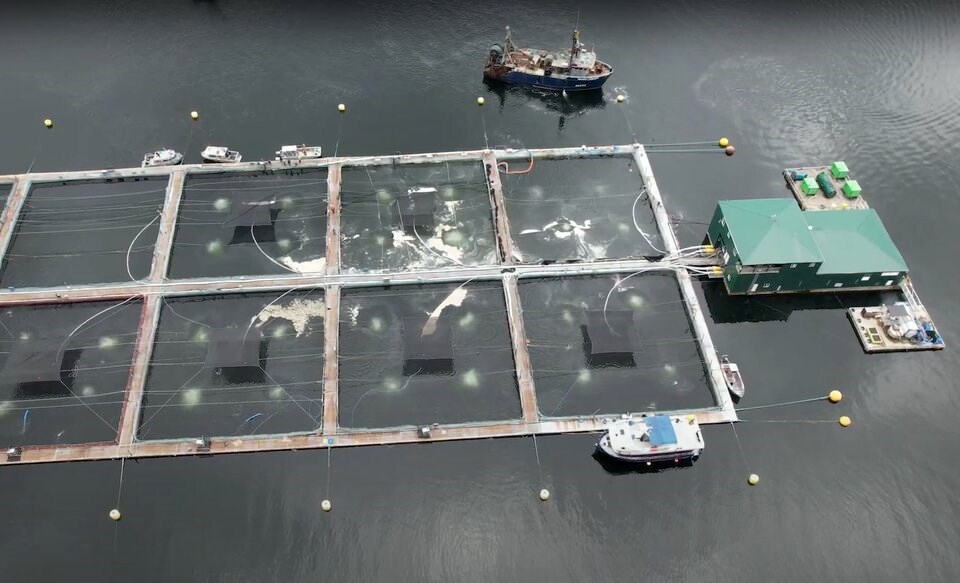

Five hours into Muchalat Inlet, Proboszcz reached the fish farm he figured was the site of a big die-off. He sent a drone into the air and captured images of what he described as “plumes” coming off the farm’s surface.

“It’s like a sheen, like an oil sheet. Maybe it’s rotting, like dead fish oil coming from the farm,” he said.

A vessel, Knight Dragon, appeared to be pumping something out of the farm, while another hose appeared to be discharging water from the ship into the open ocean.

Proboszcz said he suspects they were sucking out dead fish that had sunk to the bottom of the farm’s nets, then blowing the sucked-up water out of the ship’s hold.

But without evidence, he could prove nothing and figured he had come too late to see the scale of the mortality event.

The scientist camped on the nearby coastline, and when he returned, he contacted the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Up to 1,000 tonnes of fish lost on one farm

In emails seen by Glacier Media, Brenda McCorquodale, DFO’s senior director of aquaculture management, said in a response to Proboszcz that the department was investigating the die-off allegations and couldn’t comment further.

McCorquodale told Proboszcz the die-offs were not isolated to a single farm, but “that elevated levels of mortalities have been occurring recently among farmed fish at farm sites in Clayoquot Sound, Port Hardy, Clio Channel, Esperanza, and Nootka.”

McCorquodale said three of five open-net pen farms run by Grieg Seafood had reported mortality events in recent weeks. The highest was at Muchalat North, the farm Proboszcz had kayaked by, where McCorquodale said that over a 10-day period, 23 per cent of the farm’s stock was lost.

The farm is licensed to hold up to 4,100 tonnes of salmon, meaning a 23 per cent loss could have meant nearly 1,000 tonnes of dead salmon.

When Glacier Media asked a DFO spokesperson about the death rates, they said cumulative mortalities at each salmon farm ranged even higher — from four per cent to 26 per cent between mid-May and early June.

DFO biologists and veterinary staff travelled to Nootka Sound. They “confirmed that the mortality events were caused primarily by environmental conditions: extremely low oxygen events and harmful plankton in the marine environment,” wrote the spokesperson.

The DFO spokesperson said rain followed by sunny weather have led to algae blooms and low oxygen in the past.

In her emails to Proboszcz, McCorquodale pointed to an event in 2019, when a plankton bloom in Clayoquot Sound led to “significant losses for a number of farms.”

DFO did not answer questions about why oxygenators on the farm did not prevent the death of the fish, and whether sea lice or other pathogens played a role.

A spokesperson for Grieg Seafood turned down a request to answer several questions over the mortality event, instead referring to a news release on its website. The release echoed statements from DFO, saying the die-off was a result of low-oxygen conditions.

“Due to these adverse environmental conditions and in order to preserve the welfare of our salmon, we were unable to handle and perform sea lice treatments during this time, resulting in higher-than-normal sea lice counts for a short period of time,” the statement said in part.

It later added: “We remain committed to minimize interactions with wild salmon in the areas where we operate.”

Proboszcz said he has asked for veterinary reports from DFO but has not received them. He said the whole incident, in particular the reason given for the die-offs, concerns him because the farm he visited had triple the allowable limit of sea lice, while a nearby farm had 10 times that threshold, according to numbers companies are required to publish online.

“They’re having all these die-offs. Are the high sea-lice levels contributing to that? Because sea lice have been known to kill as well. We don’t really know,” said Proboszcz. “The big concern is juvenile salmon are migrating by this area. I witnessed that myself.

“What risk is that to wild fish?”

Rsearchers warn of increase in mass die-offs

Mass die-offs of farmed salmon are increasing around the world, with Canada experiencing some of the biggest and most frequent mortality events, according a study published in March.

“The worst of the worst cases are getting larger,” Gerald Singh, a researcher in the University of Victoria’s School of Environmental Studies and the study’s lead author, said at the time.

The latest die-off in Nootka Sound comes as the department works to phase out open-net pen farming of Atlantic salmon in the West Coast.

On Wednesday, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Jonathan Wilkinson said the government would provide a five-year licence extension for 63 open-net pen Atlantic salmon farms in B.C., not phasing them out until the end of June 2029, when they would be banned in favour of closed-containment systems.

Proboszcz said he was “not thrilled” about the five-year extension, but has already heard from DFO staff that the announcement Wednesday will likely be followed by a new regulatory regime that will enshrine the ban into law.

He said that should come with added surveillance of the industry, more investigations and more fines. When farms fail pathogen tests, they should have their licences revoked or be forced to cull farmed fish to protect wild salmon, he said.

Even then, however, Proboszcz does not expect the mass die-offs to end.

“We’re not going to stop watching the salmon farms,” said Proboszcz. “We just have to be vigilant.”

— With files from The Canadian Press