For those of us among the ever-diminishing number of people who lived in Britain during the Second World War, Remembrance Day has a special significance. Most of us grew up in those grim and difficult years.

In most cases, finishing high school did not lead to a start of work or to further education. Careers had to be delayed as long as our country was fighting for its survival. On Nov. 11, my thoughts go back to my friends who died so young.

There are others whom I did not know personally who are also in my special memories. They are the aircrew who flew in Wellington bombers from the RAF Coastal Command Station at Chivenor in North Devon, England.

I had married my Canadian aircrew husband, Richard Higgins, in April 1943 and moved at the beginning of June from my home in Scotland to the village of Braunton, near the air base. The next five months were a strange mixture of emotions.

There were the happy days exploring the region on a borrowed bicycle or taking the train to the pre-war holiday resort of Ilfracombe. Some days we rode bicycles to the beautiful beach at Saunton Sands, where a very small part was marked as free of land mines.

The stressful times were the evenings when my husband was to be in one of the planes sent to patrol the Bay of Biscay for eight to 10 hours, searching for U-boats. When we said goodbye, I always added: “See you in the morning,” but would I?

By the end of August 1942, 12 young men in two crews had completed the final phase of their training at No. 3 Operational Training Unit at Cranwell and were ready for posting to a squadron. The two crews had been selected to join 172 Squadron RAF Coastal Command on anti-submarine patrols over the Bay of Biscay.

After the fall of France in 1940, French west coast ports became convenient bases for Germany’s submarines that were ordered to attack all shipping bringing supplies to the beleaguered island nation. By 1942, the losses continued to be staggering. Allied naval vessels were unable to provide adequate protection, stretched as they were following the surrender of France and the addition of Italy to the Nazi side.

Between January and July 1942, Allied shipping losses by U-boats amounted to more than three million tons. It was imperative that intelligence be improved and that more attacks on submarines be made from the air. In March 1942, prime minister Winston Churchill sent a message to U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt explaining how the Admiralty and RAF Coastal Command had evolved a plan for a day and night attack on German U-boats departing from their Biscay bases.

Formed in April 1942, 172 Squadron was ready to do its part in attacking those submarines while on the surface. With the powerful searchlight called the Leigh Light slung underneath the fuselage, a crew would be able to illuminate their target for accuracy in the attack. In addition, the 22-million candle-power beam would cause confusion in those being attacked.

The new crews had arrived at Chivenor anxious to use their training and participate in this new aspect of the war. The one aircrew log book in my possession refers to their first “U-boat hunt” over the Bay of Biscay as being on Oct. 5, 1942. I do know that the crews would fly long hours at night on different routes to cover an extensive area.

One night, when the two most recent crews were both out on patrol, one was shot down. The red fire in the sky could be seen miles away, and the realization that it was their friends was to be the first of several sad incidents.

Arriving in Braunton, I had entered a very different world, where large planes flew overhead practising in daylight and people in Air Force blue uniforms seemed to be everywhere. I soon became used to my routine following my husband’s night operations.

As there were several aircrew living off base, the village shops always seemed to be the centre for the latest news. I remember being told by a shopkeeper about a crew that did not come back that morning. I heard the name but debated whether I should wait until later or rush back to waken a tired young man with more bad news.

The weather was sunny and warm in North Devon, and the evenings were bright as Britain went on Double Summer Time during the war to permit more daylight hours for work. I have no memory of ever being out when it was dark.

Sometimes we went to the small local cinema, and I vividly recall the evening of Aug. 9 when a message flashed across the screen that Italy had surrendered. As the audience was mostly Air Force, the cheers were sudden and loud, as everyone stood up.

On a few occasions there were functions in the mess, which I attended with my husband. The guard at the gate inspected my identity card before I was permitted entry.

Some days I would wait outside the gate for my husband to come out on non-flying days. One day, I noticed an officer ride out on his bicycle with a little black spaniel running beside him. I spoke about this to my husband who identified the officer as their gunnery officer, Flight Lt. Leslie Burdon, from Edmonton, Alta.

On Friday nights, there usually was an exodus through the station gates as airmen and women rushed to get the train to Barnstaple where there was more entertainment than in any village nearby. Usually, this was to visit the favourite pub, and it seemed each crew even had its special place to sit. Although I did not drink, I remember sitting with the whole crew of six one evening. It seemed a happier and noisier group that poured out of the train compartments on the homeward journey.

Happiness in wartime is a fleeting condition, and tremendous shock and sadness was about to befall the squadron in late August. In the afternoon of Aug. 25, the whole squadron was positioned in front of a Wellington aircraft for a picture. In the centre of the first row sat the commanding officer, Wing Commander Rowland Musson, and his senior officers, who also formed his crew. Later that day, the CO’s crew and my husband’s were among several others who were to take part in anti-submarine patrols.

In the early evening, we said our goodbyes as usual. I knew there would be a meal and a briefing before the planes would take off.

About three or four hours later, my husband burst into the room with the dreadful news that the CO’s plane had blown up not long after takeoff. This had been visible to those waiting on the runway ready to leave.

All operations for that night were immediately cancelled. We sat for some time talking. My husband was devastated, and I spoke to him of seeing the gunnery officer and his dog. That picture has never left my mind after all those years. Aged 21, Burdon was the only Canadian on that plane.

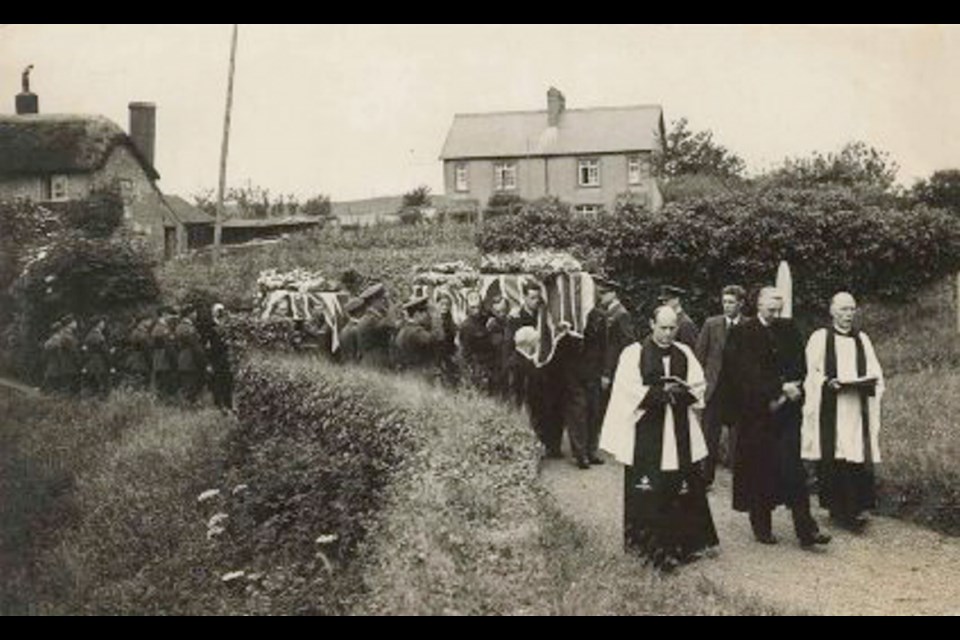

Several days later, the squadron marched up the narrow country road across from the station to St. Augustine’s Churchyard at Heanton Punchardon to lay their commanding officer to rest among his crew and so many others buried there. Following this tragedy, the RAF forbade senior officers from flying together. There would have been an investigation into this tragedy, but the result we never learned.

The night patrols continued, but the daylight practices intensified as rumours of an overseas posting were discussed. Finally, on Oct. 29 the senior crews were sent as a detachment from their home base to increase the coverage of the Biscay area. First, they spent several days in Gibraltar before moving to a new base in the Portuguese islands of the Azores.

I knew I had been fortunate in those five months to live among brave young men, to listen to their chatter and to feel some of the tension they must have experienced on those dark nights alone for hours flying over water. Now thinking back, they were all so young.

Years later, on a visit to the New Zealand Air Force Museum in Christchurch, my attention was drawn to a figure of a man in aircrew uniform standing in a display that included a poem. I stood there for a few moments and let my mind drift back to those days so long ago as I read the words:

My brief sweet life is over,

My eyes no longer see,

No summer walks —

no Christmas trees —

No pretty girls for me,

I’ve got the chop, I’ve had it,

My nightly ops are done,

Yet in another hundred years,

I’ll still be twenty-one.

Stella Higgins was a Scottish war bride who became one of the original students at the University of Victoria and received a master’s degree in history. She has spent many years doing research and writing on military topics.