Were you to find yourself among the million or so pilgrims who visit the 7th-century Ise Grand Shrine every year, as a westerner you might be forgiven for asking your Japanese companion: “But is it real?”

This is the holiest of Japan’s Shinto shrines, which until recent times housed the Imperial crown jewels. You are not allowed into the shrine complexes themselves.

If you could, you would see an enclosed range of timber structures, but nearby a duplicate set under construction. This is because ever since it was first built, the shrine has been ritually duplicated every 20 years. Your colleague would insist it is the authentic Edo Period shrine.

Problems, mainly and supposedly ethical, surrounding the reconstruction of historic buildings, or even large bits of them, have long bedevilled architectural conservationists.

Ever since a group of European conservator-savants began discussing the issue at meetings starting in Paris in 1956 (and culminating in the Venice Charter for professional ethical practice in 1964), recreating large parts, let alone whole buildings, has been frowned upon.

Even the massive historical reconstruction programs to recreate the bombed-out city centres across post-war Europe were viewed as fanciful at best, deceptive at worst. The result was the doctrine of “minimalist intervention.”

In part, this was a reaction to 19th-century restorations during which large parts of monuments, particularly churches, were enthusiastically rebuilt, or even “completed” by somehow entering into the spirit or collective mind of the original builders.

In Britain, William Morris and his circle decried the activities of the restorationists at the time. He opposed any stripping away of later changes or additions to historic monuments, insisting that these were important as evidence of the evolution of buildings over time.

The technical term for the reconstruction of buildings from original or new elements is “anastylosis.” Rigorously applied, any new parts should be readily distinguishable from the original. This is an intellectual ideal, of course. In practice, it often doesn’t play out that way.

The heritage conservation program for Victoria’s Old Town has evolved since its beginnings in the 1960s. Indeed, changes in restoration practices mark the Canadian development of the profession itself.

So, it is not surprising that the local industry, and even the city’s conservation policies, are guarded on the practice of recreating lost parts of buildings, and pretty much silent on recreating entire structures.

But conservation thought and practice are changing. The idea of the urban landscape as an archaeological site, or agglomeration of artifacts, is increasingly challenged by the view that buildings are a repository of our communal heritage, that is memory, traditions, stories — our culture.

Completeness, “the thing as it originally looked,” is much more highly valued — at least in the popular imagination.

Recently, the Globe and Mail, on discovering that a local developer had reconstructed the long-lost lantern tower on a 19th-century hotel in Cabbage Town, Toronto, found the idea so novel that it devoted a full page to a description of the project.

One can see these ideas play out in local restoration projects such as the one at the southeast corner of Yates and Broad streets. An early rehabilitation project, this was a range of structures popularly known in recent years as the A&B Sound building.

Before that, it was occupied for many years by one of Victoria’s most popular boutique hotels, the King Edward. Three of Victoria’s most prominent architects contributed to its evolution from 1895-1906: Thomas Trounce, John Teague and Francis Mawson Rattenbury.

The restoration, to say the least, was certainly restrained. The facades were stripped of stucco overlay; a minimalist skirt at the first-floor level now binds them together. But little survives of the richly decorated Victorian frontage of the original hotel. Stripped of its Late Victorian finery, today its rather sad façade hardly hints at its celebrity design lineage or storied life as one of Victoria’s finest early boutique hotels.

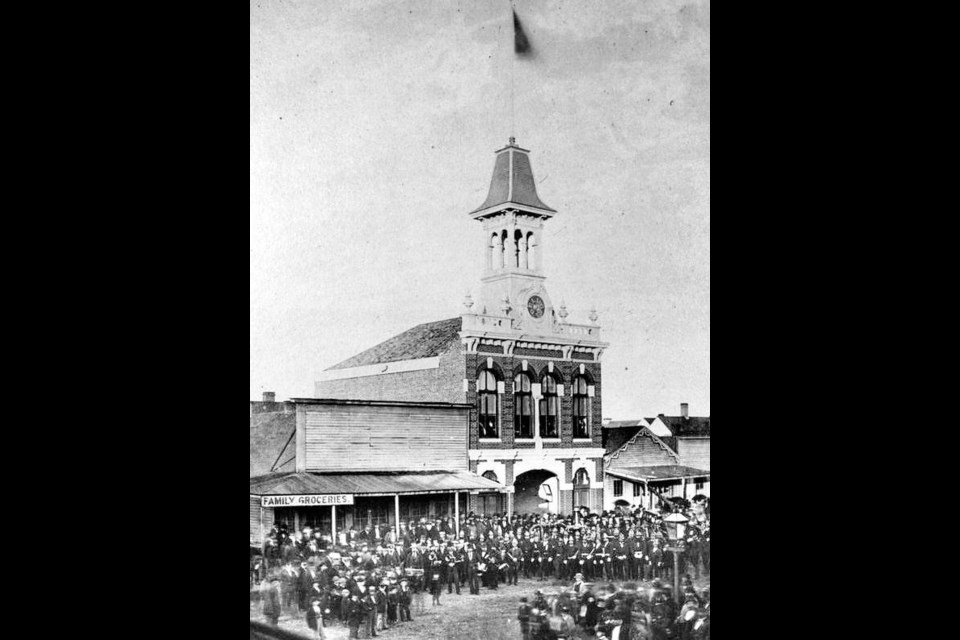

The remains of the King Edward are in sharp contrast to the Deluge Fire Hall across the street. Meticulously restored under the direction of architect Nicholas Bawlf, this 1877 ornate Italianate building designed by John Teague marks the era of the firefighting companies that openly competed both for your protection and for monumental presence on the street.

Unfortunately, it has lost its unique identity as a firehall, as the distinguishing bell tower is long gone and was not reconstructed as part of the restoration.

The nearly adjacent Reynolds Block commanding the northwest corner of Yates and Douglas streets has suffered similar ignominy. The elaborate façade, constructed in 1889 in the eclectic style of the Late Victorian period, was revealed after the removal of several billboard-size advertising signs some years ago.

However, the distinctive conical tower that anchored the street corner awaits reconstruction. This feature was probably a hint at monumentality on the part of its first occupant, Kellog the druggist, and also an attempt to upstage Thomas Shotbolt, who operated a competing pharmacopeia under one of the most elaborate pieces of cornice art a few blocks away on Johnson Street.

A couple of years earlier, Shotbolt had aggrandized his own shop at 585/7 lower Johnson St. by dressing it up and adding a rooftop shrine containing the signature of his trade, a mortar and pestle.

It signalled not only the success of his business but also his rising status as an investor in numerous enterprises, and the completion of a fine house and country estate occupying most of present-day Gonzales. Here is another case for recreation. The entire upper floor — a masterpiece of the tinsmith craft — is now gone.

Other lost towers in the Old Town include the lantern tower above the 1883 Oriental Hotel, once a major landmark, atop the otherwise exemplary rehabilitation of an iron-front building on lower Yates Street.

Old Town’s Victorian cornice work, limited only by the creativity of the designer, talents of the tinsmith and pocketbook of the owner, once constituted the city’s most vibrant public art form. Age, along with weather, fire codes, seismic risk, but particularly the dreaded scourge of “modernization,” has severely depleted the stock of these often-delightful examples of roof-top whimsy.

It was therefore a bit of a disappointment to see that the ornately bracketed parapet, once the crowning glory of the recently restored 1991 Adelphi Hotel (formerly Fields Shoes) at the corner of Government and Yates, could not be included in the developer’s budget. Perhaps another time!

The Victoria Civic Heritage Trust offers special grants for cornice restorations, but a glimpse at the streetfront elevations of Old Town suggests the opportunity this funding provides has not been accessed nearly enough.

A quick look at the Edwardian-period benevolent-society buildings that anchor Chinatown reveals an interesting distinguishing feature, upper-floor inset balconies.

A common amenity tracing its heritage to the streets of Hong Kong or Shanghai, wooden multi-storey balcony verandahs once towered above the sidewalks of Fisgard and Herald streets.

Historically most significant, and originally very imposing, was the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society Building on lower Fisgard.

Unfortunately, only fragile-looking metal appendages that replaced the elaborate multi-storey timber galleries can be seen today. Given the importance of Chinatown as a National Historic Site, at the very least the verandahs should be rebuilt.

Beyond missing parts of buildings, however, there is also the question of missing buildings. On lower Yates Street, in the otherwise near-complete 500 block of restored 19th-century buildings, a gaping hole displays the steel structural reinforcing buttresses for the two adjacent imposing warehouses.

These constituted one of the earliest restoration projects in Old Town. The decision to remove the street-front façade rather than stabilize it as a screen was taken at the last minute. Reconstructing at least the frontage should be reconsidered.

Adding back missing parts, or even immediately reconstructing buildings lost to catastrophic circumstances, is less controversial than recreating buildings that were demolished in the distant past.

They are deemed gone forever, and if a replacement is needed to complete an historic streetscape, then a ubiquitous “sympathetic infill” is recommended. The Union building filling in the block between lower Fisgard and Pandora streets is an example. But this common practice of infill is being challenged.

European urban conservation practice today is increasingly embracing the idea of historic recreations.

Recently, the 1950s Modernist rebuild of Dresden’s central Neumarkt Platz was itself demolished in order to recreate the earlier Hanseatic merchant houses. The centrepiece, however, is the just completed Frauenkirche.

The reconstruction of this elaborate Baroque church, including its once renowned interior mosaic decorations, used traditional materials — albeit informed by the application of contemporary engineering algorithms and computer-assisted stone-cutting technology. The $1-billion cost was raised by public subscription.

Reconstructing historic monuments for political purposes is becoming an industry. The 18th-century Kazan Cathedral in Red Square, Moscow, completely demolished by Stalin, was fully rebuilt in 1993.

The Humboldt Centre recently opened on the Museumsinsel in the cultural heart of Berlin. It is the centrepiece of a set of monumental neo-classical buildings housing Germany’s national museums. The Humboldt is encased in a faithful exterior reconstruction of the earlier 18th-century Prussian Imperial Palace.

The original palace had been demolished in 1950 and replaced with a modern one to house the East German Parliament (Palace of the Republic). A new Modernist design that was proposed to replace the now-redundant parliament met with mass protests. As part of the campaign, activists mobilized 1,500 artists to create a full-scale five storey mock-up on site.

A more positive attitude toward historic reconstructions could play a significant role in repairing the historical integrity of Old Town.

The offer by a developer to reconstruct the Canada Hotel as part of the Duck Building rehabilitation should have been taken up. On Government Street at Johnson, the burned-out site of the former Century Inn, originally the Edwardian classical Westholme Hotel, awaits reconstruction.

A major gateway monument, the hotel marked an entrance to nearby Centennial Square and Chinatown.

But there is one major monument surviving as Old Town’s largest archeological ruin that does deserve some serious consideration.

The Wharf Street harbourside retaining wall visible from the parking lot below Bastion Square is the last surviving remnant of the massive Hudson’s Bay Company trading warehouse.

The warehouse was built in 1858 to assume the commercial activities of the fort as gold replaced fur as the economic foundation of the city.

This monumental building, which dominated the townscape for nearly 100 years, represented the very reason for Victoria: the HBC fort and its trading partners in the Songhees village ranging along the shoreline across the harbour.

The massive brick warehouse also symbolized a pivot point in Northwest Coast history when a fairly amicable accommodation between First Nations and the European fur trading companies gave way to formalized colonialism.

From the Songhees perspective, as John Lutz points out in his book Makuk, on the trading history of First Peoples in British Columbia, the notion that the Europeans were guests on Indigenous territory had started to evaporate.

Yet in all likelihood, Songhees skilled artisans were employed in the construction of buildings such as this, as they had been the fort.

The economic spinoffs from the Songhees acting as middle-men in coastal Indigenous trade, along with “hosting” the thousands of Indigenous visitors who arrived every year from as far afield as Alaska, produced considerable wealth for many local families.

For more than 50 years after the 1843 establishment of the fort, this relationship underpinned one of the richest potlatch cultures in the Pacific Northwest.

The ritual continued even after the dominion government banned potlatches in 1888 as both the local white and Indigenous communities ignored the Ottawa directives.

Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie, from his bench in the Supreme Court Building on the other side of Bastion Square, had long been sympathetic to the plight of First Nations now under Ottawa’s thumb. He threw out the first attempt at prosecution on the grounds that the law was unenforceable.

Would it be such an outrageous idea to imagine a reconstruction of the HBC warehouse, which could then contain a visitor interpretation centre telling the story about the 150 years of this highly complex trading economy, its replacement with settlement colonialism, and lessons to be learned from the resulting suppression of First Peoples’ rights and cultural expression?

Local architect Chris Gower has suggested we could reimagine the warehouse scale and form, but expressed in contemporary materials. His resulting design proposal could be adapted for use as a museum or festival centre.

At the very least, the surviving masonry wall, long neglected and it seems all but forgotten, deserves an interpretive panel explaining its critical but nuanced significance in the history of Victoria.

Martin Segger, a long-time resident of Victoria, is an architectural historian, two-term city councillor, and former co-chair of the Provincial Capital Commission. He is a research associate at the University of Victoria Institute for Global Studies.