A group of researchers working in British Columbia and Russia has discovered a new supergroup on the tree of life — microscopic predators that both swallow whole and nibble their prey to death.

The discovery, recently published in the journal Nature, reveals 10 strains of what the researchers are calling provora, or “voracious predators” — complex single-cell organisms collected during a decade-long hunt across the planet’s seas, beaches and lakes. Together, they begin to fill a blind spot in cellular evolution and bring scientists one step closer to piecing together the tree of life.

“It’s like saying that we just discovered animals existed for the first time,” said Patrick Keeling, a professor of biology at the University of British Columbia and one of 12 co-authors on the study.

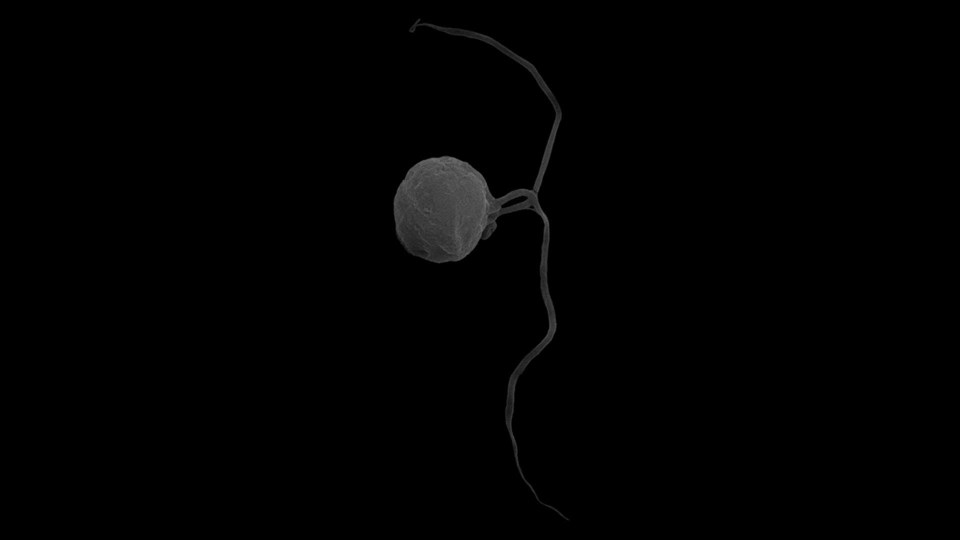

Roughly five micrometres long, provora measure less than a third of the width of the smallest human hair. That makes them invisible to the human eye.

But peer down at one through a microscope, and you will see a complex cell possibly chasing down prey with the swish of flagella — microscopic tails that can whip cells into motion.

There wouldn’t be much distinguishing the two classes of provora: nebulidia and nibbleridia. But watch them for a time and you would see two different beasts.

“They have different behaviours. One group eats its prey. It literally just swallows cells whole. The other has a tooth — they’ll gang up in a swarm and nibble it to death,” said Keeling, who prefers calling provora “nibblers and lions.”

That prey includes other complex cells, which themselves eat bacteria. If the microscopic world were transposed to the Serengeti, it would be like lions eating wildebeest, and wildebeest eating grass, said Keeling.

Only in the case of provora, there’s a vast world of larger predators ready to devour them and pass their nutrients up the food chain.

The star of life?

The discovery of the new supergroup marks a major advance in the understanding of the diversity of life, but it also underscores how much we don’t know about ecosystems playing out at a microscopic scale.

Keeling has been working his whole career to piece together the history of life on the planet. In recent years, he says, scientists have found the diverse kingdoms of animals and fungi — two separate twigs on the tree of life — share a close evolutionary relationship. Until recently, the two kingdoms were thought to make up one of six supergroups of complex cellular life.

That is, until nibblers came along. Their discovery adds a seventh supergroup, a branch so different it likely diverged from the tree of life a billion years ago, said Keeling.

“They’re as different from each other as humans are from bakers’ yeast,” he said.

Since its earliest conceptions, the tree of life has been reworked as scientists learn more. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution still underpins humans’ understanding of how life has changed over billions of years.

But at the viral or bacterial level, research into lateral gene transfer — which involves one organism absorbing stray genes from its environment rather than its parents — has led some to rethink whether a branching tree accurately represents how life has evolved on this planet.

Keeling, whose PhD supervisor, W. Ford Doolittle, was a major contributor to the understanding of lateral gene transfer in the evolution of certain cells, says a version of the tree of life still has explanatory power when trying to envision the planet’s web of complex life.

Consider a star instead, suggests Keeling. Provora would represent a ray striking from one point to another.

“It’s a new branch,” the researcher said.

Scouring the planet for invisible predators

The discovery would never have been possible without exploration. Over a decade ago, Keeling met Russian scientist Denis Tikhonenkov at a conference. Soon, Tikhonenkov was travelling from Russia to British Columbia every year for four months at a time to collaborate with his Canadian colleagues.

One of the first discoveries of a provora was almost by accident. Tikhonenkov had arrived at Keeling’s lab at UBC and thought he would see what would sprout up if he added some growing medium to a dirty piece of equipment left behind by another scientist. What came to life was unlike anything they had ever seen.

“We sequenced and took pictures. But it didn’t fit anywhere in the tree. We thought, ‘Gosh, is this an orphan? Has everything related to it gone extinct, or is this the tip of the iceberg?’” said Keeling. “It turns out it was the latter.”

In the coming years, the researchers would collect provora samples across the world, from the Arctic Ocean to the coral reefs of Curaçao and the Red Sea. One species — dubbed Ubysseya fretuma — was found 220 metres below British Columbia’s Strait of Georgia between Richmond and Gabriola Island.

Much of the work would be impossible to complete in the same way in recent years. First, the COVID-19 pandemic restricted travel; second, Russian and Canadian scientists, once close colleagues, are increasingly separated by the war in Ukraine, says Ryan Gawryluk, a biologist at the University of Victoria who helped sequence the provora’s DNA.

Some of the samples in the study were taken from Sevastopol Harbour, where the Russian navy keeps its Black Sea Fleet. In November, a co-ordinated naval drone attack is thought to have damaged a frigate near the harbour, and this week, Russian forces claimed to have shot down an aerial drone after a powerful explosion was heard nearby, according to one Ukrainian news outlet. In short, war has returned to Russian-occupied Crimea, making science a near impossibility, says Gawryluk.

“Sending DNA and RNA for sequencing, it would definitely be difficult now,” he said. “It probably wouldn’t have been possible.”

Both B.C. scientists say Tikhonenkov has a knack for finding tiny creatures. When or if the researchers can once again carry on their work could affect what more is learned of the new supergroup. And there’s a lot more provora waiting to be discovered, suggests the group’s genetic analysis.

“There’s a rare biosphere of predators out there that are numerically rare but important,” said Gawryluk. “We just don’t know what’s there.”

Supergroup illuminates evolution and crisis

Finding the rest of the provora supergroup would help give scientists a fuller picture of how life evolved. Because there are no fossils of microbes, scientists like Gawryluk have to work backwards from what’s living now, deducing what life’s common ancestor might look like — or as Keeling put it, “basically billion-year-old archaeology.”

“These very open-ended studies involve flipping over rocks, digging in the dirt and scraping the ocean floor,” said Gawryluk. “Sometimes you hit it big and find things that fundamentally helps you understand the evolution of life on this planet.”

But understanding the breadth and diversity of microscopic life also matters to those who still inhabit the Earth, says Keeling.

Species across the planet are going extinct at a rate not seen since the disappearance of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Nearly 200 countries are currently working toward a global agreement to halt and reverse biodiversity loss — nature’s life-support system — at the COP15 summit in Montreal. Through it all, we must not forget about lifeforms invisible to the naked eye, Keeling says.

“There’s a system on this planet that makes it habitable to us and everything else we love,” he said. “The foundation of this system that keeps us alive is not dolphins and marmots on Vancouver Island.

“It’s microbes.”