The Royal Canadian Navy says it takes great pains to protect whales, so it was a shock in August when skippers of Victoria-based whale-watching boats reported ugly confrontations with sailors during blasting on Bentinck Island.

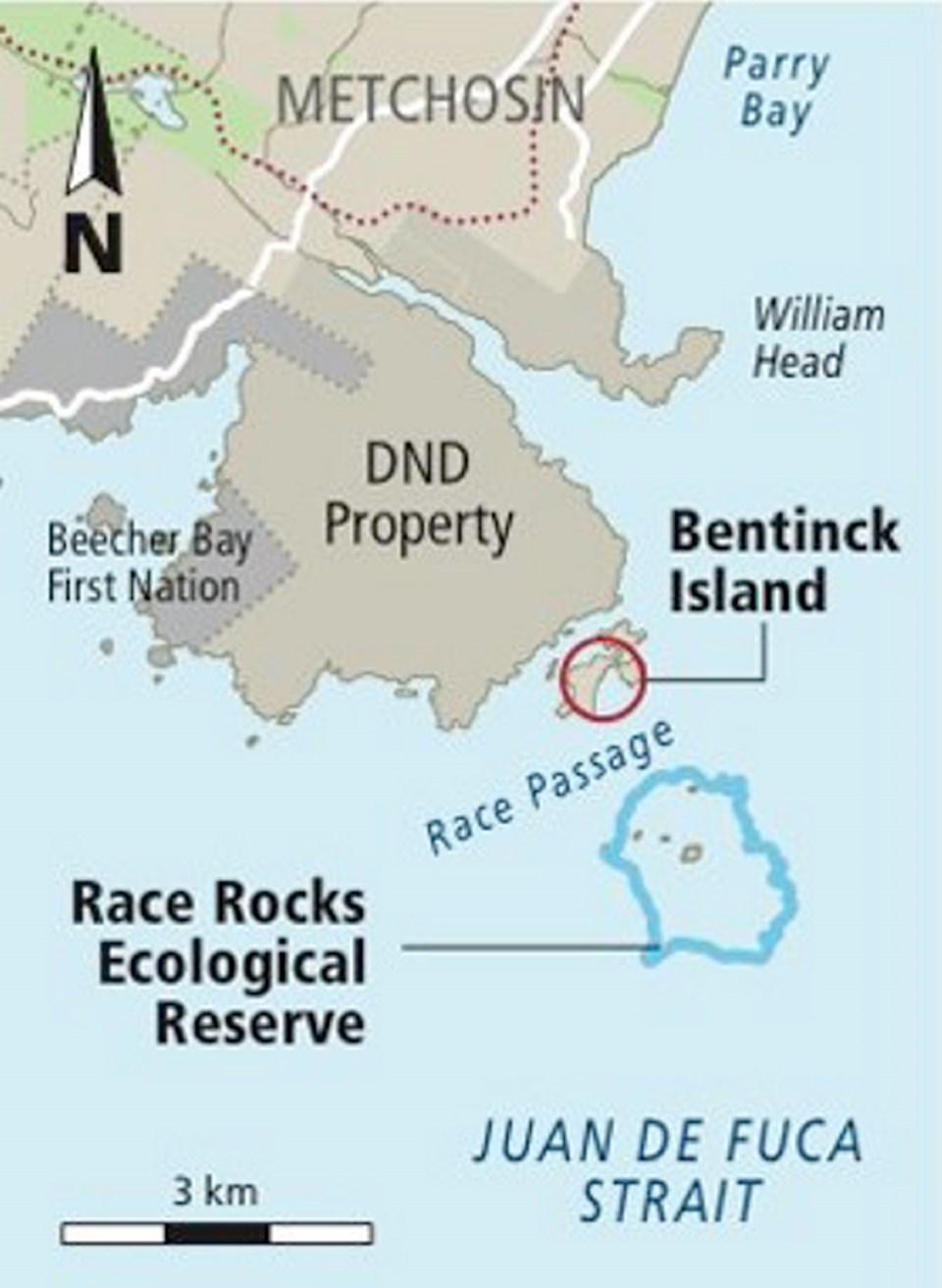

Navy officials say they try to avoid endangering passing orcas and humpbacks, just as they take care to protect the ecology of Bentinck Island and the nearby land on shore occupied by the Department of National Defence at Rocky Point in Metchosin.

Its sailors and officers make their homes in Greater Victoria. Like any other residents, they say they want nothing to harm the unique elements of living on southern Vancouver Island, whether it’s marine mammals, migrating birds or the other animals and plants.

Its sailors and officers make their homes in Greater Victoria. Like any other residents, they say they want nothing to harm the unique elements of living on southern Vancouver Island, whether it’s marine mammals, migrating birds or the other animals and plants.

“We are actually quite proud of the environmental protection we have in place,” said Commodore J.B. (Buck) Zwick in a special media session.

“We take our roles as environmental stewards very seriously,” said Zwick, who commands the Canadian Fleet Pacific and Naval Training System.

In incidents on Aug. 3 and Aug. 31, whale-watching skippers confronted navy sentries posted in small boats off the island during a blasting session. The whale-watching skippers tried to convince the sentries to call off the blast because orcas were nearby.

Instead, the whale-watchers were told it was too late. The fuse was already lit, and safety procedures forbid any attempt to stop it. According to the whale-watching skippers, when the explosions occurred on the beach minutes later, the creatures were obviously distressed.

The incidents were also a shock for whale-watchers, who say they have always enjoyed a positive relationship with the navy.

Dan Kukat, owner of Spring Tide Whale Watching and navy liaison for the Pacific Whale Watching Association, said in the August incidents, whales were spotted approaching the blast zone, the navy was notified but the blasts went ahead regardless.

Whale-watchers worry the acoustic vibrations from the beach blasting interferes with and even harms the whales. The creatures are echo-locators and make their way around underwater obstacles using sound and echoes.

Kukat emphasized several times he and members of his association have nothing but respect for the navy. It’s just sometimes the natural world could use a break.

“In these days now, when it’s not entirely necessary to defend the country, let’s think about defending the environment, too,” he said in an interview.

The navy, however, maintains it was complying with its Marine Mammal Mitigation Procedure. It’s a 15-year-old document that instructs sailors on what to do at Bentinck Island when marine mammals approach during blasting activity.

It requires sentries, posted in boats 1,000 metres offshore from the beach, to look out for whales. When whales approach within two kilometres, the sentries radio the officer in charge of the blast range, who can shut things down.

In the past, the navy has conducted acoustic studies. They show underwater noise from the land-based explosions is negligible compared to the normal ambient noise levels a whale encounters.

Nevertheless, since August, the navy has taken a second look at its demolition training and how it interacts with whales and whale-watchers. It has halved the maximum amount of C4 plastic explosive to 2.5 pounds from five (1.125 kg from 2.25 kg).

The navy says halving the size of the explosive charge will make no difference to the demolition training for sailors and service people. The noise will be slightly less above ground and water.

“The process is the same, the quantity of the charge makes no difference, except for a bigger bang,” said Capt. (N) Martin Drews, commander of Navy Training and Personnel.

“But it’s important to use live ammunition during training because it helps instil a sense of discipline in our sailors,” said Drews.