This is the third instalment in a six-part series, exclusive to the Times Colonist, that examines the role of the provincial government in the uprooting, detention, dispossession and exile of Japanese Canadians, 1941-1949.

Yoshio John Madokoro had been a fisher as long as he could remember. He and his family lived and worked out of Tofino. A Canadian born in Steveston, he had taken up fishing at 15 after his dad died. His fishboat was impounded along with hundreds of others soon after Pearl Harbor.

In his recollection of those years, Madokoro recalled being forced to leave Tofino: “By the time the Maquinna came in it was toward evening. We were all standing on the dock. It is vivid in my memory. I was saying goodbye to my white friends and watching the families. People would come up to me because I was the secretary and they would say: ‘Can I take my camera?’ And I would say: ‘How should I know? Sure, go ahead, take it.’

“In Port Alberni, the provincial police were waiting for us at the docks,” continued Madokoro. “They took us to the local police station. After they checked their lists, something that would become routine to us, we were loaded on the CN train to Nanaimo. We were becoming more known as anonymous numbers and less as individual members of a community. You know that is what really hurts even to this day: we were stripped of our identities and treated as ‘undesirables’ even though we had not committed any crime. Our crime was being Japanese Canadian! Canada has a funny way of dealing with its own citizens.”

As Madokoro recalled, the British Columbia Provincial Police (BCPP), a provincial agency, was involved from day one in the uprooting. Nor was the province’s involvement restricted to its police force — it was also a key player in the British Columbia Security Commission, set up to supervise the uprooting. And whenever necessary, the province intervened directly with the federal government to impose their policies.

The British Columbia Provincial Police

Founded when the province was still a British colony, the BCPP expanded to a force of more than 500 officers in 120 detachments before it was disbanded in 1950. As recounted previously, the head of the BCPP, T.W. Parsons, had accompanied provincial labour minister George S. Pearson in early 1942 to Ottawa, where he backed the provincial government’s plan to clear the coast of Japanese Canadians.

Upon his return to Victoria, he wrote to the provincial attorney-general, R.L. Maitland, to press for the mass removal of Japanese Canadians, a message that Maitland then forwarded to Ottawa.

Shortly after the federal government acceded to the province’s campaign for mass uprooting, Maitland wrote to the RCMP, assuring them that provincial and municipal police forces would fully co-operate in forcibly removing Japanese Canadians from their homes.

According to Lynne Stonier-Newman, author of Policing a Pioneer Province: “The uprooting proceeded methodically. The RCMP handled most of the work in Vancouver and New Westminster, and the BCPP organized the exodus from Vancouver Island and the Coast.”

Yoshio Madokoro recalled: “When we got there, they took us to Hastings Park and what they gave us was a horse’s stall. You’ve never seen anything like it, just a horse’s stall. We had to do our own cleaning up and everything. What a smell!”

From Hastings Park, the BCPP “assumed almost all responsibility for policing the Japanese nationals and citizens as they were transferred to the interior.” According to former BCPP officer Don. N. Brown, thousands “were interned in various camps in the interior of British Columbia — all under the control of the BCPP.”

The BCPP, at the direction of the province, had become an integral part of the uprooting from start to finish. But the province’s role did not stop there.

The British Columbia Security Commission

Provincial appointees were key figures in the British Columbia Security Commission established in March 1942 to supervise the uprooting and establishment of the camps.

At the top, the province agreed to the appointment of B.C. Provincial Police assistant commissioner T.S. Shirras, one of a triumvirate of commissioners to head the Security Commission.

The Security Commission’s advisory committee included provincial attorney-general R.L. Maitland; minister of labour, George Pearson; and the leader of the CCF, Harold Winch.

The Security Commission’s plan to ship men out to work camps without their families generated resistance. Dozens of men, including Johnny Madokoro, formed what became known as the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group, demanding that families be kept together. A riot broke out in Vancouver’s Immigration Building, with protesters pitching the contents of rooms out of windows.

Even then, the Security Commission refused to allow husbands and wives to stay together. In scenes reminiscent of U.S. President Donald Trump’s border policies today, families were torn apart. Johnny Madokoro ended up in a work camp in Ontario, his wife Mary and the children in the Slocan detention centre in the Kootenays.

Those that continued to protest were shipped out to prisoner-of-war camps, as recounted by Robert K. Okazaki in The Nisei Mass Evacuation Group and P.O.W. Camp 101. Though Canadians, they were illegally detained in the camps for years, denied even basic rights under the War Measures Act.

Back in detention camps in B.C., travel outside of the designated sites was banned by the Security Commission under the War Measures Act: “No person of Japanese origin at any work camp, village, farm, municipality or other area to and in which they have been duly authorized or directed to proceed shall leave such place without the authority of the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or Provincial Police delegated by the Commission to carry out such orders and supervision.”

The B.C. Security Commission’s final report concluded that “this Commission could hardly have functioned without the assistance of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the British Columbia Provincial Police,” the latter under the control of the provincial government.

For many of those incarcerated in camps, it was impossible to make ends meet without working. Still, the provincial government refused to let detained Japanese Canadians work in the forests. Provincial secretary of state George S. Pearson wrote to the federal government: “Re Wire October twenty eighth reference to Japanese our government is not satisfied that it is wise to allow Japanese to work in lumber industry in British Columbia without police supervision.”

Premier John Hart reiterated this in a telegram to Ottawa: “Referring to our conversation regarding the proposal to employ Japanese in timber cutting, please be advised that this matter was caucused quite recently and was definitely turned down. The members were absolutely against the Japanese being employed for that purpose. I would appreciate your advising the Honourable C.D. Howe as to the result of this Caucus.”

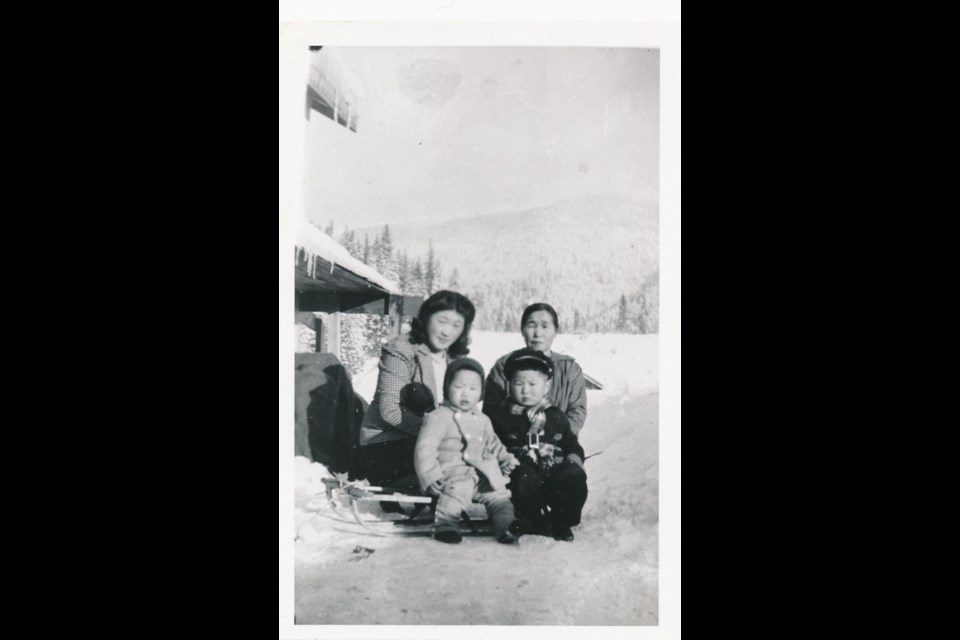

While detained in Slocan, Mary Madokoro struggled to get by, often using her last pennies to buy food for the family, including her young children. It took more than two years before the family eventually reunited, in Toronto, thousands of miles away from their beloved coast. By then, their Tofino home had been sold, without permission, as had Yoshio’s boat.

Like many Japanese Canadians, the Madokoro family survived the uprooting, but at what cost?

A decade would pass before Yoshio, Mary and the family could return to B.C. When they eventually got back, in 1953, Tofino refused to allow Japanese Canadians to return. So, the Madokoros bought a house in Port Alberni. Their daughter, Marlene, still lives there. She says: “As a third-generation Canadian of Japanese descent, I am proud of my grandmothers, parents, aunts and uncles who showed integrity, strength and resilience during their uprooting and internment during [the Second World War].”

The provincial government was deeply involved in what happened to Marlene’s family and thousands of other Japanese Canadians. Not only was it a main instigator in the uprooting, not only were its agencies and officials involving on a daily basis in overseeing the camps, it also denied education to thousands of children who remained in detention in camps in B.C.

Next week: Part 4 — Punishing the Children

John Price is professor emeritus (History) at the University of Victoria and the author of Orienting Canada: Race, Empire and the Transpacific and, more recently, A Woman in Between: Searching for Dr. Victoria Chung (with Ningping Yu).