First in a six-part series

In 2012, the British Columbia legislature adopted a motion introduced by Naomi Yamamoto, the first person of Japanese heritage elected to the provincial legislature, to apologize for events during the Second World War when “Japanese Canadians were incarcerated in internment camps in the Interior of B.C. and their property seized.”

Celebrated by some, the motion also had its critics. Now, the National Association of Japanese Canadians has asked the B.C. government to go beyond the 2012 motion, fully acknowledge its own responsibility, and adopt initiatives that would assure the events of that era are never repeated.

In this exclusive series, we examine what the National Association of Japanese Canadians is asking for and why. The series drills down into the provincial government’s role in the 1941-49 period, highlighting the impact on communities and illustrating why the community may indeed have a strong case.

These articles rely on the foundational research conducted by Ken Adachi, Ann Sunahara, Roy Miki, Mona Oikawa and others, as well as on research conducted in Library and Archives Canada, the B.C. Archives, the City of Victoria Archives, University of McGill Archives, local newspapers and interviews with Japanese Canadians to whom the author is indebted.

The research is in preparation for a new book, Beyond White Supremacy: Race, Indigeneity and Pacific Canada.

Full disclosure of B.C. government documents related to the uprooting remains elusive. A select list of resources and fact-checking information for this series is available upon request.

The National Association of Japanese Canadians will be heading to the British Columbia legislature soon to ask the government to fully account for its actions that led to their uprooting, dispossession and exile from the coast from 1941 to 1949.

The NAJC will be presenting the result of community consultations in a report entitled “Recommendations for Redressing Historical Wrongs Against Japanese Canadians in B.C.” The contents of the report will only be released next week when it is formally submitted to the provincial government.

Federal sanctions against the community are well known. In 1988 the federal government provided redress, but unfortunately the provincial government’s role remains shrouded, even though it passed a government apology in 2012.

The provincial 2012 resolution offered its regrets for what happened, but failed to acknowledge the government’s own role in the devastation of the community, or to provide any measures of redress. Even worse, the government failed to consult the National Association of Japanese Canadians beforehand.

Community disenchantment with the provincial motion culminated in a NAJC decision to take action to address the problem, and thus the consultations.

NAJC president Lorene Oikawa is ready to move forward: “We look forward to negotiating with the B.C. government on the next steps for meaningful measures to redress the violation of rights and financial and other losses for 22,000 Japanese Canadians, and to address the intergenerational impacts of government actions. By helping to ensure a degree of justice for Japanese Canadians, the B.C. government can help safeguard against any such future injustices.”

For the past five months, a Redress Steering Committee has held extensive consultations with communities in British Columbia and across the country, as well as co-ordinating an online consultation forum to determine what might be included in a submission to the provincial government regarding appropriate measures it might take to help move the healing process forward. A small grant from the B.C. government assisted the largely volunteer effort.

Community meetings were held in Burnaby, Kamloops, Vernon, Kelowna, Nanaimo, Victoria, Vancouver and New Denver, as well as in Toronto, Winnipeg, Hamilton, Calgary, Ottawa and Edmonton. The cross-country consultations were necessary because the majority of more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians who were uprooted during the war never returned to B.C.

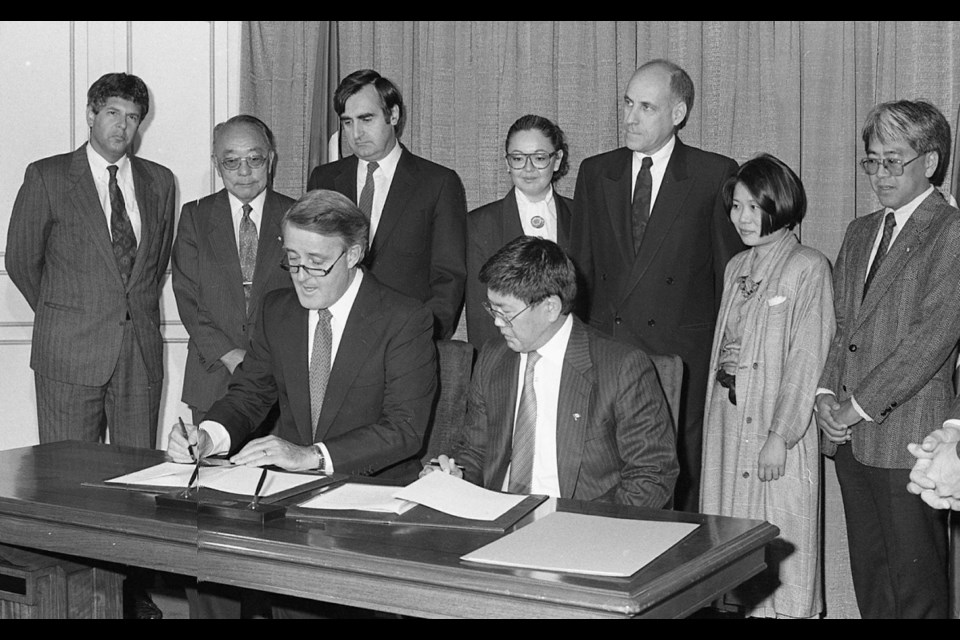

The federal government addressed its wrongdoing in 1988 after a long campaign by Japanese Canadians and their allies across the country. Art Miki and Maryka Omatsu, negotiators of the 1988 Federal Redress Agreement, stepped up to co-chair the B.C. Redress Committee in charge of the consultations on behalf of the NAJC.

Omatsu believes many people in the province remain ignorant of the virulent racism that was the culture of B.C. for much of its past. Not only did the B.C. government dispossess First Nations, it passed more than 170 anti-Asian measures.

“Still,” says Omatsu, “in perusing the B.C. education curriculum for reference to the Japanese Canadian experience, there is very little. Often all it says is that Japanese Canadians were interned as were Ukrainians and Germans.”

Though Ukrainians and Germans suffered from discrimination, the dispossession of Japanese Canadians was on a different level, says Omatsu.

“Our communities were destroyed and people came through this experience traumatized, with accelerated loss of language and culture and a 90 per cent inter-marriage rate … that trauma of this magnitude has inter-generational impact is accepted as fact.”

Raising redress issues can pose dangers. A recent opinion piece supporting B.C. redress prompted this anonymous response: “What a laugh. How long are Japanese Canadians going to milk this issue? Have they no shame?”

Such resistance is not new to Mary Kitagawa (Murakami). Uprooted with her parents and siblings from Salt Spring Island, she led a long campaign to have the University of British Columbia address its responsibility for kicking out Japanese Canadian students: “First of all, I found out that UBC administrators knew nothing about the Japanese Canadian experience,” she says.

“I more or less had to educate them, and it took a long time.”

She’s unsure whether things are better: “Whenever we speak, people are stunned that such a thing occurred. A lot of people, especially young people, are unaware of what happened.”

Recent research suggests she and the NAJC may have a case.

The only major study on redress education, by Dr. Alexandra Wood, concluded that educational efforts were lacking and that “the federal and provincial government must work harder to demonstrate that their apologies are more than empty pledges, and to counter charges that multiculturalism policies whitewash the past.”

Masako Fukawa, a well-known writer and educator who lobbied the provincial government to provide a learning resource about the Japanese Canadian experience, recalls she had “a running battle with the then-deputy minister of education to get them to fund such a resource.”

Eventually they did, Fukawa says, but problems remained: “Teachers have a lot of say regarding what is taught in the classroom and they teach what they themselves have been taught, so unless we work with them, the education just won’t happen.”

Ignorance surfaced during the recent election, when Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party of Canada misused a photograph of Japanese Canadians boarding a train in Slocan, prompting the NAJC to respond: “This photo depicted in Mr. Bernier’s video is not a moment of welcoming new Canadians. It is a moment depicting Japanese Canadians being derided and subjected to sweeping, merciless political violence. We remain puzzled if Mr. Bernier endorses such actions or if this was an error as a result of ignorance to past injustice by the Canadian government.”

The NAJC hopes that legacy measures suggested in their submission to the B.C. government will help overcome the ignorance.

“Only a negotiated agreement between the government of B.C. and the NAJC will resolve this long-standing historical wrong,” said Omatsu.

“Just as the Japanese Canadian community did not accept the 2012 apology, which was written without formal consultation, the Japanese Canadian community will reject a ‘take it or leave it’ offer.”

Next week, Part 2: Engineering a Coup

John Price taught history at the University of Victoria and is the author of Orienting Canada: Race, Empire and the Transpacific and, recently, A Woman in Between: Searching for Dr. Victoria Chung.